An Unexpected Connection

written by: Elizabeth Bowden-David

My mother passed away several months ago. In my season of mourning, a chance discovery emerged: a peek into a phenomenon so startling, so mind-bending, and ultimately so comforting that it transformed how I comprehend personal connection.

My mother passed away several months ago. In my season of mourning, a chance discovery emerged: a peek into a phenomenon so startling, so mind-bending, and ultimately so comforting that it transformed how I comprehend personal connection.

This chance revelation, while the product of fleeting moments, is best understood in the context of decades. For most of my adult life, my mother and I kept up with each other’s lives long-distance as she stayed rooted in Alabama while I trotted the globe. The telephone, more than any other object, captures my mother’s essence, and by extension, our relationship.

As far back as I can remember, a 1920s vintage phone hung on our family room wall. A wooden structure about two feet high, it had a receiver to hold to one ear, a horn-shaped mouthpiece to speak into, and round silver bells that once clanged. It spoke to a bygone era, when the newness of being able to instantly reach others far away must have been marvelous indeed. I think Mother kept it on display not only for its shellacked beauty, but as a nostalgic symbol of interpersonal connection.

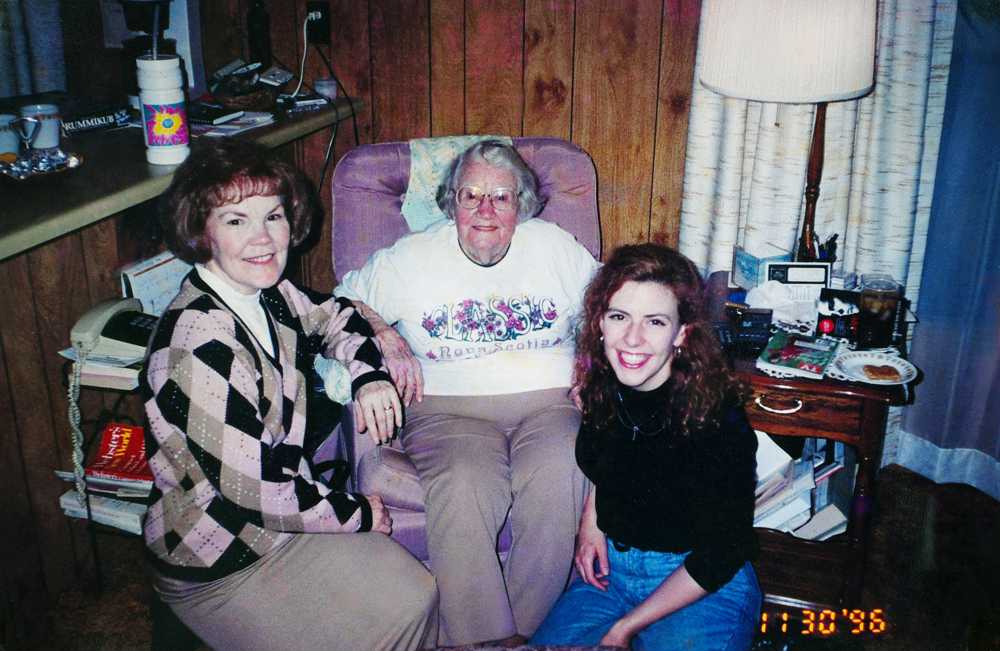

The first “call” I had with her – aside from our pretend conversations on the antique phone – was over an intercom at KMart. Wandering off in big stores, I often wound up on the aisle with Little Debbie snack cakes – not just because I craved sweets but also because I believed the Little Debbie logo was a depiction of my mom. A spitting image: wavy red curls, high cheekbones, gracefully arched brows, and the sweetest of smiles. That day at KMart, I pretended to be lost. I approached the service desk and asked them to page her, using a fake name.

“Will Mary’s mother please come to the front?” was soon broadcasted.

As Mother liked to tell it, she thought, “Well, there’s Elizabeth,” and turned her cart around.

At home, the first usable phone I remember was olive green with a stretchy, curly cord and a rotary dial. Her long, beautiful nails didn’t fit inside the fingertip circles, so she dialed by using the eraser end of a pencil.

She phoned across town daily to check in on her own mother, Mama Wood. Mother revered Mama Wood but also watched over her, making sure her groceries were stocked up and her checkups were on track. For any need, Mother dialed one of her six siblings: Uncle Bob for electrical or plumbing repair; Aunt Dot for casserole and pie recipes; Aunt Anita for a belly laugh; Uncle Charles for details of a forgotten story; Aunt Wanda for a no-nonsense opinion; Aunt Audrey for a companion to scoot around with on errands.

But for a listening ear – whether comfort for a thorny problem or just the space to hear one’s own thoughts aloud – the phone would ring at our house. Mother would clear her throat, intone a melodious, three-syllable “Hel-LO-oh,” and sit down at the kitchen table.

Siblings, friends, Sunday School classmates, and neighbors all called. Her contributions to most conversations were chuckles, little gasps, and remarks like “My word!” or “How ‘bout that?” She’d stay on the call as long as the other person wished. Even that most Southern of all telephonic phrases, “Well, let me let you go,” rarely passed her lips.

And she doodled. No fancy artwork – just scratches on a notepad or in the margins of a bill. Maybe she needed something to keep her hands occupied during these listening sessions. In the evenings, before I set down plates for dinner with my parents and my brothers Alex and Stuart, I’d clear away papers filled with her squiggles, shapes, and curly-q’s.

After some years, we upgraded to a sunshine yellow phone with a push-button dial and an even longer curly cord. She seldom took advantage of the stretchy cable to multitask. Rather, she sat down, gave her attention to the other person, and doodled. A new feature, call waiting, became available: if someone called while you were already on the phone, a little beep sounded. She hated call waiting! No way could she bring herself to interrupt a talker. In fact, she had a corkboard to which she thumb-tacked a cartoon of a boy praying, “Lord, thank you for never putting me on hold.”

The cozy area around the phone told a lot about her personality – the corkboard, a chalkboard on which she dashed off reminders, a calendar she made containing everyone’s birthdays. Shoeboxes of neatly organized bills and receipts. A daily devotional booklet. And phone books! She taught me how to use the white pages and yellow pages, along with the World Book encyclopedias and a medical dictionary a few steps away, to hunt down any information I needed. She was Googling long before Google.

Affixed to the wall next to the yellow phone was a handwritten register of numbers. Mama Wood’s was near the top. My calls to my grandmother always started the same way:

Mama: “Hello!”

Me: “Mama?”

Mama: “Well heeeeeeyyyy, darlin’!”

It didn’t matter whether she recognized my voice right away. There were 21 of us grandchildren, not counting great-grandchildren and in-laws, all of whom called her by the same name. Her progeny were so numerous that she referred to the Wood descendants as Splinters. Each Splinter got mentioned in her nightly prayers and qualified as a darlin’.

Another number on the register was Daddy’s office, but we knew that was for emergencies only. Mother respected his working hours and created a little window of quiet relaxation for him each evening.

“Let him unwind,” she taught us. “Don’t just hit him with a problem when he walks through the door.” She would push two palms forward to illustrate, revealing a sympathetic insight that poorly timed or ill-chosen words could have a physical effect.

Daddy’s evening arrivals ran like clockwork. Mother timed her errands so she’d be home, lipstick refreshed and hair in place, to greet him in the house foyer. He’d loosen his necktie on the way in, prop his feet up on the hassock, and unfold the copy of the Birmingham News she had placed on the sofa for him.

When I left for university, the decades of our mostly phone-based relationship began. Daddy, for all his beaming smiles and bear hugs whenever I made the two-hour drive home, was never much of a phone talker. Mother, however, was happy to connect even for small matters, like a personalized wake-up call on the morning of an exam. Important announcements, such as the birth of my nephew Micah, were also relayed by a voice-over on the receiver.

Three weeks after baby Micah’s arrival, my father lay down for a nap one afternoon but didn’t wake up. I was thankfully home. I dialed 911 for an ambulance, and later called Mama Wood to tell her it wasn’t looking good. In her “I’m sorry, darlin’,” I heard grief for her daughter’s new widowhood. Family soon surrounded us – in the ER itself and later at home, giving us the comfort Mother had always so readily offered to others.

On my visits home in the years that followed, I noticed that the phone bills were still addressed to Hilton Alexander Bowden. I think it comforted Mother to see Daddy’s name. I asked once whether she would consider remarrying. After all, she had years stretching before her and might have enjoyed companionship.

“No,” she shook her head emphatically. “I’ve got my husband.”

As ever, the kitchen table contained evidence of her doodling. There were more pages to scribble on now, as the bills from the phone company were thick and listed all her long-distance calls one by one. International calls, something she probably never expected to see on her bill, began to appear.

She didn’t always support my desire to explore. One summer, I worked at a backpacker joint on a Greek island, and I was planning to journey from there to Israel to harvest oranges and experience kibbutz life. But over the phone, she explained a complex situation, concluding that I needed to return to Alabama for insurance purposes. I do not believe she intended to manipulate me, but within days of my return, I found out it had been totally unnecessary.

“I just thought you’d like to come home for a while,” she admitted.

I exploded. I continued to explode throughout the winter while I scrounged for money and passed time. She hounded me, unable to respect my independence. I was right to pursue my own life, but I am deeply sorry I hurt her. In a painful memory, we argue in the car as she drives down Highway 31. Her gracefully manicured fingers cover her mouth as she begins crying, right there behind the steering wheel.

“It seems like you want to cut all ties,” she weeps. Her breaths are so short that she can’t say this sentence all at once.

Somehow, we got through that season, and I returned to my traveling life. She must have made peace in her heart with our distance. We never really spoke of what made her finally let go, but she never hounded me again. Not for anything.

News, both joyful and sad, was relayed across thousands of miles. In Prague, I received a mischievous call as I eagerly awaited the birth of Micah’s brother or sister. Mother spoke slowly to draw out the anticipation.

“The baby has been born, and…the…name…is…………………….Anna Elizabeth. How ‘bout that?”

In Phoenix, I put a quarter in a payphone outside a restaurant to announce that Griffith had just proposed marriage. In my excitement, I temporarily forgot which numbers to push. In Helsinki, I answered her call in the middle of the night to learn Mama Wood had departed. I remember seeing my reflection in the hallway mirror, holding the receiver as my knees gave way.

Griffith and I continued years of globe-trotting, and our sons, Naveen and Gabriel, were born. Mother relished chats with her grandsons. Never a tech enthusiast, she nevertheless figured out how to make a cassette recording for their bedtime. (I play it on an old boombox sometimes to remember her voice.) She reads out The Happy Man and His Dump Truck, tells them she loves them, and wishes them good night.

Mother upgraded to other tech only insofar as it brought her closer to people she loved. A cordless phone allowed her to take the receiver downstairs to the laundry room so she wouldn’t miss a call. An answering machine allowed her to replay messages from her growing grandchildren. A car phone – along with a handy little printed card of relatives’ numbers that read “Who ya gonna call?” – assured others she could reach help if needed. Finally, a flip-mobile enabled her to connect to anyone, anywhere.

More years passed, and her memory began to slip. She alarmed family and friends by calling, sometimes at odd hours, and repeating a discussion from just minutes before. When I flew in, I found half-eaten Little Debbie snack cakes and spoiled food cluttering the fridge. The kitchen table was littered with unsorted mail. Her doodle pad was a messy collection of shards of conversations. Written diagonally: “Alex will take me to the doctor. Why?” A medical assessment confirmed our dread, and difficult decisions followed. My brothers and I sold her house and most of her furnishings. Uncle Bob wisely rescued the antique phone. We moved her into an assisted living community, where she was safe, happy, and clueless about the presence of her disease.

When the cost of that facility was no longer sustainable, my brother Stuart took her into his home in Memphis. She basked under Stuart’s watchful care. In our calls, which grew ever shorter and narrower, I invariably heard one phrase:

“I’m just sitting here enjoying Stuart’s company.”

On one of my whirlwind stops in Tennessee, my friend Karen came along. We watched as Stuart sat Mother on a chair, brushed her tresses, and brought out a can of hairspray.

“I do this so her hair doesn’t fly around when it’s windy outside,” Stuart explained.

Karen later mused, “If I were to make a movie like Love Actually, your brother spraying your mom’s hair would be the very best scene.”

Mother lived for 12 years after her diagnosis and fared far better than any of us had dared to hope. I even caught a glimpse once, for nearly two stunning hours, of a sudden resurgence in her memory. But most calls were a two-minute, tape-recorder chitchat. One early spring day this year, she had a different remark:

“It looks like I’m in the hospital.”

At that very moment, Stuart was calling Alex from the emergency room, explaining that our mother had broken her hip. I booked the next flight from India, boarded when she was coming out of surgery, and walked into her hospital room 28 hours later.

For the next few days, I held her soft hand, cajoled her to eat applesauce, and slept on the visitor sofa. Initially, she lived in a state of hallucinations. Keeping her eyes half closed, she muttered words so quickly that they were hard to decipher, but there was a clear theme: calling her mother.

She didn’t recognize me when the hallucinations were at their height, instead seeming to consider me a helpful bystander. She asked me to ring her mother to come pick her up. She rummaged through her purse for coins.

“I don’t have a dime, but if you would call her from a payphone, I’ll compensate you.”

In the middle of one of these nights, I was startled awake as she shouted, “Mother!” It was a desperate child’s tone in an elderly voice.

As the hallucinations came and went, lighter topics emerged, such as how to make banana pudding or wanting to get her hair done. I was amused as she told me, still a bystander, about her baby daughter.

She wrinkled her nose. “Elizabeth is rambunctious and persnickety.”

At some point, she settled down and seemed sure of one thing: Her mother was coming to get her. I knew that post-surgery hallucinations were common, but at the time, I thought she might be in the process of passing. Every time she paused, I watched carefully for another intake of breath. I couldn’t shake the feeling that there was more to it than a medical reaction.

Gradually, her cognition returned to her pre-surgery state, she recognized me again, and she moved to a step-down facility for hip rehab. We spent pleasant hours together, with conversations brief and narrow, but gentle and sweet. When it came time for me to return to my life in India with Griffith, she let me go with a relaxed smile.

One month later, a WhatsApp call from Alex, too early in the morning to be good news, made my knees give way. Again, a booking of the next flight. A dizzying week of practical arrangements and collective grieving. In the funeral home, reaching down to touch her gracefully folded hands with their elegant nails. On the hillside, both joy and tears as her casket was lowered next to Daddy’s. Somehow, it shocked me that I hadn’t been by her side when she passed. Nearly half a century earlier, she had been with family at the bedside of Papa Wood, and she sometimes spoke of his last breath.

“You could see it, that moment. You could see the instant life went out of his body.” Her hands always moved in an upward gesture with these words.

And Mother had been present for Mama Wood’s last utterance, which, according to everyone in the room, was, “Time to go.”

But neither I nor any other family was there for Mother’s last words or last breath. The rehab staff noticed labored breathing and called an ambulance, and she passed shortly after reaching the emergency room, even while Stuart was stepping out to drive to her.

“I don’t think I’ll ever get over it,” I told Alex before the funeral, “the fact that she was alone then. Just doctors and nurses.”

Once back in India, I started looking through the journal I had kept during Mother’s hospitalization. I suppose I wanted to cement the events in my mind by reexamining my notes. There it all was on the pages in my curvy handwriting – her rummaging through her purse for a dime, calling out at night, eventually saying her mother would come get her at 5:25, telling me how to make banana pudding….

Saying her mother would come get her at 5:25.

In the midst of raw grief, a chance discovery. I started converting time zones in my mind, thinking backward to what time I had received Alex’s call, what time Stuart would have called Alex before that, and when the authorities would have informed Stuart.

Keeping the 5:25 number to myself, I requested medical records and held my breath. Days stretched on. Finally, the file came in.

Patient with no pulse / no spontaneous respirations / pronounced dead at 5:29 p.m.

And this from Google: Doctors typically wait a few minutes after breathing stops – about five minutes, with a range of two to 10 minutes – to make the declaration.

Did she call her mother? Did her mother call her? Were there summons to or from my father, my grandfather, her departed siblings, or anyone else? It’s a mystery I can live with. There’s a lightness in my chest now, a free space that I once thought would be weighed with lifelong regret.

At 5:25, in month five of the year ‘25, in those last moments at the hospital, Maida Elizabeth Wood Bowden was not alone. This precious woman, whose life centered on bonding with those she loved, made a connection in the end far beyond anything a curly yellow cord, a clunky car phone, or a flip-mobile could ever provide. And she never needed that dime.

NOTE FROM THE AUTHOR:

This is a follow-up to my essay published on 22 December 2024, An Unexpected Gift.

- An Unexpected Connection - January 22, 2026

- An Unexpected Gift - December 22, 2024