Dead Fish

written by: Sid Senthilvel

There’s a body in the bathtub. It’s rotting, hollow black pits where eyes used to be, a hanging jaw dotted with yellowed teeth, skin the color of cold milk. The stench is unbearable, somewhere between fancy cheese and a beached whale. One arm dangles outside the tub, long fingernails scraping the tile. It’s soaking wet, as if it just emerged from the ocean.

You’re brushing your teeth one night, brushing hard enough to make up for the fact you don’t floss, and accidentally make eye contact with it.

It waves. You hesitantly wave back.

“Kiddo, you should really floss.” It tells you, which seems rather hypocritical, given the state of its own teeth. You say as much, and it laughs uproariously. It’s closer to a hacking cough than any sort of laugh you’ve known. It’s still cackling when you quietly shut the door, toothbrush still covered in paste foam.

You try bringing it up in conversation every so often. A reference to the smell here, an open door there. No one notices.

One day, you drag your dad up to the bathroom and point at the body. He looks confused for a moment, then something happens to his face, and suddenly he looks very sad indeed.

You don’t understand, how can he not see what’s so obviously there? The body even waves at your dad, but he doesn’t do the same back. Why is that?

“You’re crazy, kiddo.” Says the body, wiggling its rotting toes in your bathtub.

“It’s how you say hello!” You don’t really believe him.

You haven’t showered in days, because it won’t let you lift it and won’t get out on its own. You’re beginning to stink worse than the body, you think, sprawled out on the bathroom floor, trying to mimic the way it’s wiggling its toes.

You tell the body that it takes crazy to know crazy, and it nods wisely.

Your parents are worried. They’re always worried these days, about what you don’t know, because they never tell you. School must have started again, given the changing seasons, but you never went back after last year. Something must have happened, you think, something big, but whenever you try to think of it your head starts to hurt.

You ask the body what happened last year, because it seems to know what’s going on.

“Someone died. Drowned. Older than you, I think.” Its head tilts to the side, as if pondering. “Dunno why the folks would be so broken up over it, though.” You shrug, taking a bite out of the apple you’re having for breakfast. It tastes like fish.

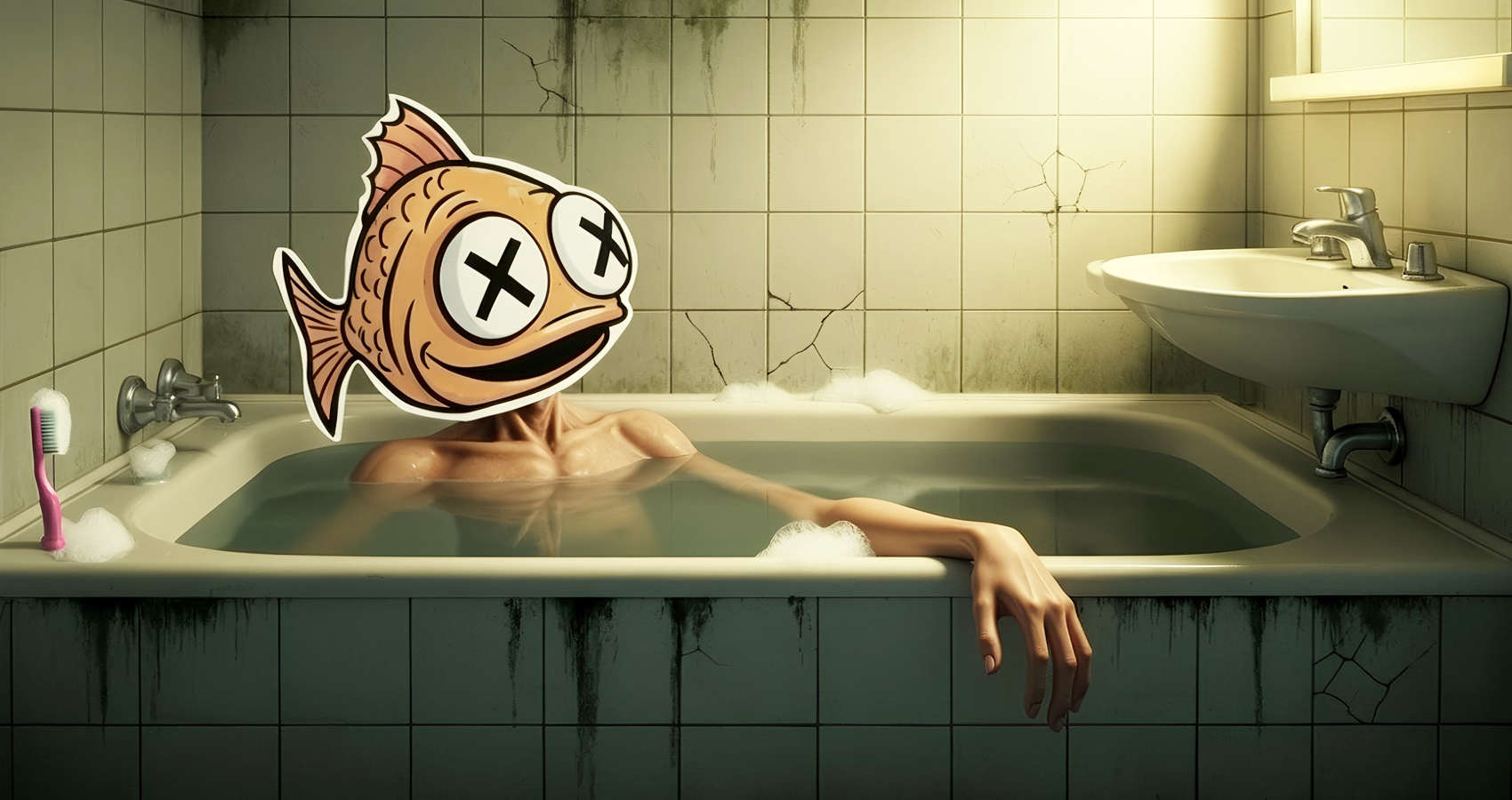

You spend most of your days on the bathroom floor, listening to the body talk. You can’t remember what it says, only that it spoke, and you listened. Your dreams are frenzied, clashing visions of ice-cold water and blood-curdling screams, melding into images of dead fish with big cartoony X’s over their eyes. They’re cute, in a morbid way.

Your parents took down most of the photos in the house last year, before the body was in the bathtub. But there is one, a family portrait you all got taken a couple years ago. You were still small, barely tall enough to clear your mother’s hip. The frame is nice, if a bit dusty, and it looks altogether pretty normal, but something about it still catches your eye.

One night, you creep downstairs and just stare at the photo, knees drawn to your chest, eyes fixated on it. You and your mom are sitting on a nice-looking chair, side by side, and your dad is standing, his arm on the back of the chair as he smiles for the camera. There’s something wrong with it. After hours of sitting there, one detail comes to mind.

Mom and dad fought that day. Dad drove Him to practice instead of the photoshoot.

You fall asleep, knees still tucked to your chest. You’re shaken awake by your mom, who looks oddly distressed. You ask the body what the detail means that evening.

“Hell if I know, kiddo.” You fix it with a deadpan stare. It snickers.

Weeks pass. You definitely stink worse than the body now. You hear shouting matches from your place on the bathroom floor. Something’s happening, but no one wants to tell you what.

It’s driving you a little crazy.

Your dreams don’t improve either. Now you’re spending most nights in the bathroom as well as the days.

It builds to a crescendo a few days later. Tonight, the screams are louder than ever; a shouting match for the ages. Even the body winces as the door slams, rattling the soap dispenser so hard it falls into the sink. You hear the car start and peel out into the street. The house is quiet. You sigh, leaning against the wall. You need a break.

Creeping down the steps, you reach up on your tiptoes to the shelf that’s always been just out of your reach, and grab a bottle. You grab two glasses as well, just to be polite.

“Cheers.” The body gulps down his share, and you do yours. You get through about half the bottle before a rolling wave of nausea washes over you, and in a second, you keel over. You vomit into the toilet bowl, while the body cackles raucously. It keeps laughing until you stop. A bitter chuckle escapes your lips, then another, then another, until you’re laughing along with it. It’s a scream, a wild dance of limbs and sounds, rising up, up and up.

You pass out into the toilet bowl.

You’re floating in cold, bitter water. A dead man floats alongside you. His body is rotting, and his head has been replaced by a fish’s, with big cartoony X’s over the eyes. He turns to look at you. His fishy mouth contorts into a smile, and he wiggles his toes in greeting.

“Hey there, kiddo. Wanna go for a swim?”