A Fishy Tale

written by: Adele Evershed

@AdLibby1

They say we women are invisible, but we’re not. We are just overlooked, and that’s a different thing altogether. Men have always worked at sea, harvesting the fish and the stories. They strode with such big steps and rigged their boats with such clattering it was easy to forget they were the ones who were invisible for days or weeks at a time. But without us, they would have been left like fishes out of water.

God knows we worked hard; my hands looked like they belonged to an old woman, the skin on my fingers crisped and peeling from all the soaking. Sometimes I wished I could turn into a fish myself, I’d let my skin harden into scales, and with a flick of my tail, I would leave my life behind me.

I lived in Haddam, although it has never felt like home. My family always had one hand on the Bible and one on the tiller. You see, fish swam in our bloodstream. The men made their living on the Connecticut River, and the women silently mended the nets and filleted the fish for market. So, I knew this would be my life from the age of being able to heft a bucket.

When I was young, I was expected to collect the scraps of bone and offal and feed them to Jessie, our pig. I loved Jessie; she was such a gentle presence in my life. When I was with her, I could forget for the longest moment the cruelty of the children at school. They teased me about my smell, so Jessie was my only friend. The other children acted as if they all smelt of lavender soap rather than stale sweat and mildew. I would swish my braid, clutch my lucky stone, and call over my shoulder, “I am a shad princess tasked with spying on your kind for my father the king, and one day, when we know enough about your wicked ways, he will come and sweep you all into the river.” Then I would run to Jessie’s shed and rub my tears on her soft side as she rumbled sounds of comfort to block out the echo of the jeering that had trailed behind me.

In the shed, I would take my lucky talisman out of my pocket, rub my finger in the groove, and will my heart to be as still as the milky stone. I had found it on the shore of our river when I had gone to escape the tempest raging inside our house. It looked like a charm in the shape of a love heart, and the second I picked it up, I felt my own heartbeat slow; Daddy’s harsh words dissolved like blood in salt water, and I knew that one day I would leave Haddam behind.

As I got older, the other children grew tired of taunting me. They might hold their noses as I walked past, but they never spoke to me apart from Jimmy Boulanger. He would approach crab-like, so I never saw him coming. I would feel his sticky breath on my neck, and he would pinch me, saying, “Just checking you have skin and not scales, princess.” And then he’d run away laughing. He followed me from school one day, and as I walked through Bates Field, he pushed me down. He said, “We all know you smell of rotting fish because you’re a sea witch,” and then he lay on top of me and started breathing heavily; he smelt of vinegar, and as he covered my mouth with his, I felt like I was sinking into a pickle barrel. I could feel his tongue knocking on my teeth, so I opened my mouth wider and then clamped my teeth down on his tongue. My mouth filled with rust; he screamed and kicked me as I lay on the ground, and it all felt like it had happened to me before.

I thought I might tell my mother, have her stroke my hair, and tell me it would all be okay. But when I looked at her eyes, they had sunk so far into her face she looked as if she was not there. So, instead, I decided to carry my filleting knife with me from then on.

The next time Jimmy Boulanger looked at me, I took my knife out of my pocket and ran it over my thumb. His eyes widened as I smeared my blood over my lips and licked them. After that, he never bothered me again.

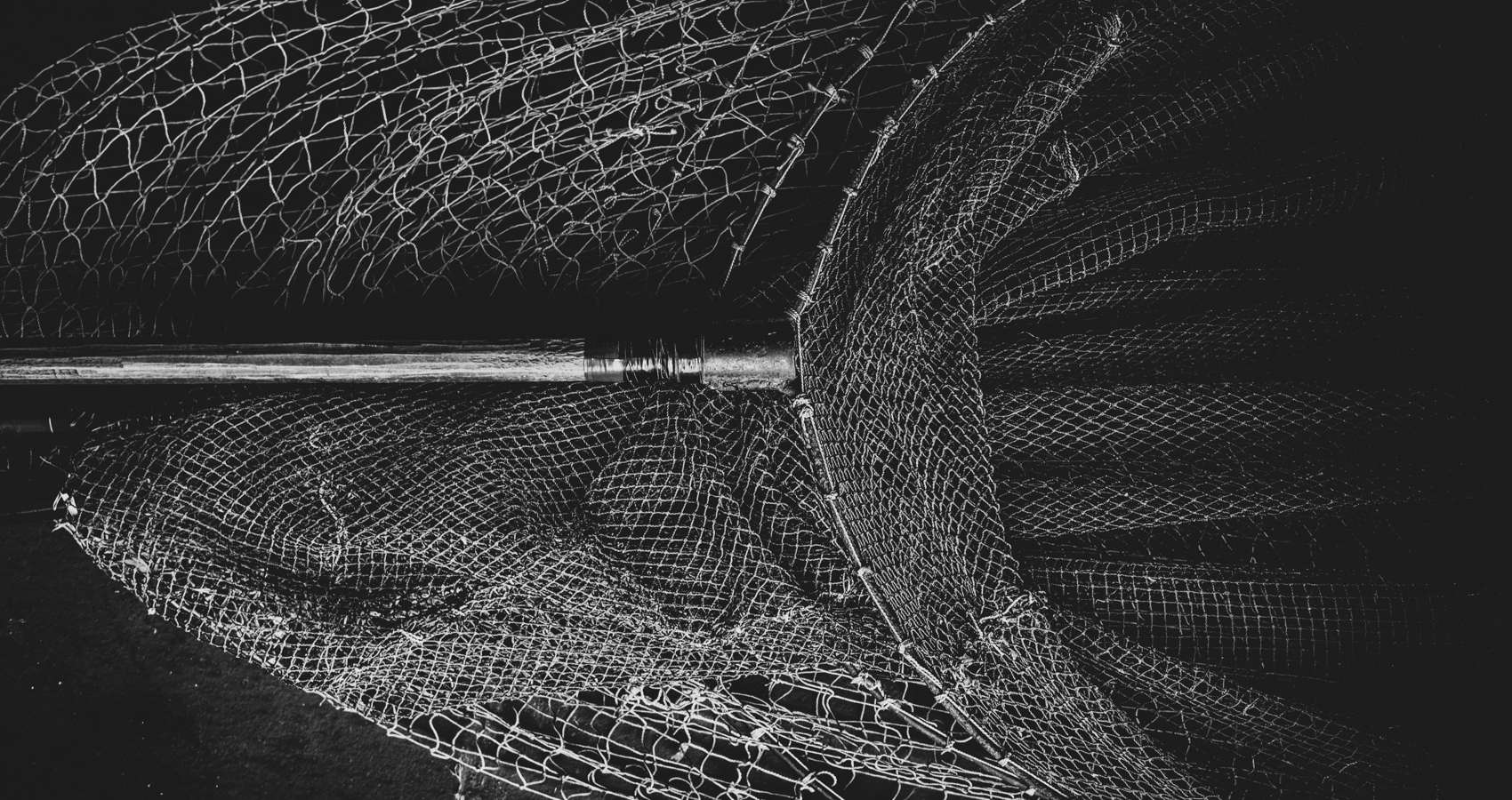

At home, Daddy would offer up the fisherman’s prayer before every meal.

“I pray that I may live to fish

Until my dying day.

And when it comes to my last cast,

I then most humbly pray:

When in the Lord’s great landing net

And peacefully asleep

That in His mercy I be judged

Big enough to keep.”

It was the prayer his Daddy taught him, and it came true for my Grand-Daddy; he was fishing on the river with my Daddy until he died. Then it was Daddy’s turn to lay his nets with his son, my brother, George. And so the wheel turned. They fished every incoming tide as soon as the forsythia bloomed its unhappy yellow alarm. At night I watched the lanterns they hung to mark their nets twinkle in the darkness and pretended they were the lights of the city where my shad family lived.

But know this if there is any justice in heaven for sins committed on earth, then our Lord will have one look at Daddy and throw him back. Daddy was as mean as a shad plank, nailing us with his knuckles until we felt the heat of coals on our backs. My mother made excuses for him, saying his goodness was dwindling with the fish. When she was a girl, the shad run was about 400,000. Now, we were lucky if we got a fraction of that.

George inherited his cruel ways, although he never raises a hand to me. Instead, he used his words as a filleting knife. Yet I imagined myself like the shad, Daddy might have removed my scales with a blunt spoon, but it takes skill to debone a shad. I had a thousand bones, and my brother was always too clumsy to master the art. He might have owned a sharp knife, but you’ll only get the sweetest meat if you have patience.

Mother and I made sure the fish that Daddy and George caught could be sold to Mr. Maynard for his Shad Shack. He fried them up and sold them to the travelers on Saybrook Road. We worked ten hours a day from April to May, and I could fillet over a hundred and fifty. Mother called it an art, and she’d been doing it for near on fifty years, but her fingers had gotten stiff, so she only managed half the amount she used to be able. I tried to make up the difference so that Daddy wouldn’t know, but it was hard.

Then one day, as I ran my knife over the bones from gills to the tail, counting the clicks like a rosary of saints, Daddy came up behind me. I’d told Mother to take a break, and of course, Daddy saw me standing at the table alone and demanded to know where she was. I told him she felt unwell and was lying down. Daddy grabbed my wrists and dragged me against the wall. Again I had that feeling this had all happened before. Daddy’s rough fingers pushed my skirt around my waist, and he was gulping, fighting for each breath. Finally, I started to scream, and he banged my head against the wall snarling at me to be a good girl. Mother must have heard us as we’d made enough commotion to rouse Jessie. She had broken through the gate to her shed and was butting against the house.

Mother saw Daddy smack me across the face as she opened the door. Then, shouting for him to stop, she launched herself at Daddy’s back. Mother shrieked, “I will not let you beat her down the way you have me all these years, you bastard.” I had never heard her raise her voice to Daddy before and, indeed, had never heard her swear at anything or anyone. The air seemed to leave the room, and I felt we were all underwater. Daddy moved in slow motion as he grabbed Mother by the throat, lifting her. I watched as she started to gasp, her legs flapping wildly like the shad when they knew they were about to die. I took my boning knife and stuck it in Daddy’s neck. I drew it across as if I was slicing off a keel bone.

I escaped to the river and washed my bloody fingers in the water. A mist was coming up, and I wrapped myself in its cloak of invisibility. I placed my stone heart on the river bank, unlaced my bones, and joined my breath with the fog as I let the Shad Spirit embrace me. And that is how I left the world of men, a world that had only ever tried to remove my spirit, ripping it away bone by bone. Then, finally, I felt I was home at last. So I flicked my tail, joining the shoal of silvery fish flashing upstream like wishes that had just come true.

- Bridging The Gap - August 9, 2025

- The Five Stages of Grief - April 5, 2025

- Moths, Moonshine and Other Things that Leave Holes - January 14, 2025