The Scientist in the Church

written by: Allison Gilliam

If I were asked, I’d tell you the last few years have been quieter in these halls. That most of the ones caring for me do not live on the grounds. They are hired, they come to the property to perform a job. Plow snow from the driveway, mulch flowerbeds, open the pool for the summer. I would tell you there is a bedroom within my walls in which the window drapes remain closed for days at a time. I would tell you my eyebrow window used to let in the light of a full moon which brightened a bed where a couple made love, used to let in morning sunlight that filled the room while they giggled under the covers, used to frame the starry night as the mother paced the floor holding a wailing child. I would tell you she is not the same, and neither is he. He no longer sleeps in the bedroom with the eyebrow window, and while his snoring did shake my walls for a time, it doesn’t now. The night sky framed by the eyebrow is seen by her alone.

My walls were built in the eighteenth century by townspeople whose Puritan grandparents had stolen the land of others in the name of God. In this hilly, wooded, rocky land carved by glaciers, the townspeople needed to form a house of worship. Backed by one of the wealthiest political families in the colony of New York, the townspeople had the funds available to build a beautiful stone Dutch church. My walls were filled with hymns, prayers, the cries of babies, laments for the dead. And then late one night, a weary man of the cloth forgot to extinguish a single remaining taper candle hanging from the sanctuary wall, locking the door behind him as he walked to the rectory for sleep. The flames destroyed the second-story balcony along with its staircase and the entire roof before finally being extinguished by a rainstorm. My walls sat empty and exposed to the elements for years. Long spears of icicles formed in the brutal winters of the New York Hudson Valley. Moss grew on my stones in the rainy springs.

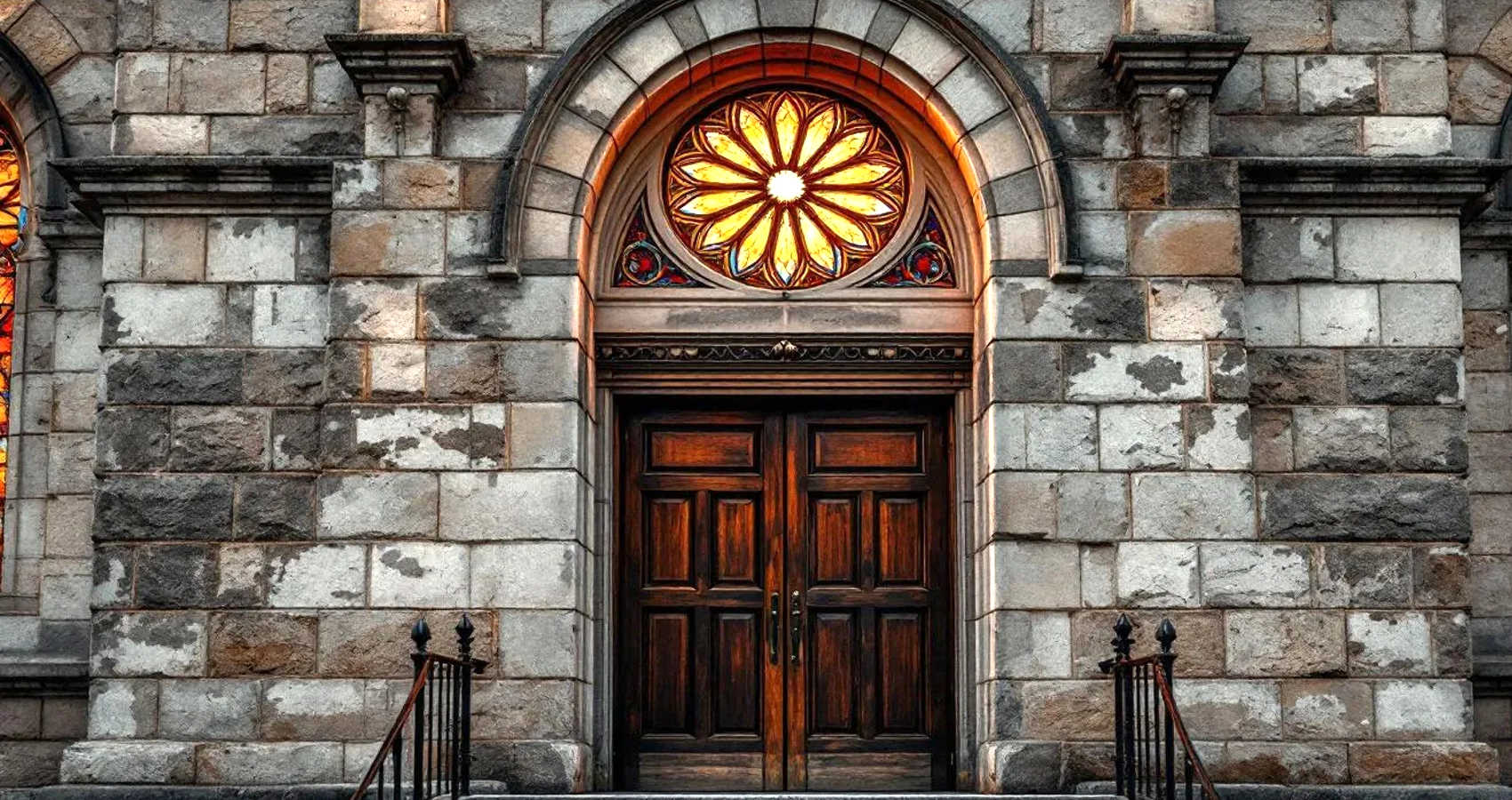

In the nineteenth century, I was restored and rebuilt. My stone walls were scrubbed, the burned and rotted wood cleared away. They gave me larger windows, long rectangular ones with square panes and Gothic points on top. They added a rosette window above my wooden front doors, built a tall steeple. A bell in the steeple called the townspeople to worship. A larger second-story balcony was built, one with an imposing and ornate curved wooden staircase leading down to the sanctuary. Once again, I was filled with song, prayers, and cries of the bereaved. Once again, I was the nucleus for each community member’s rotation of daily life.

In the twentieth century, the town merged with another community and changed its name. A railway was now nearby, but with not as many farms. My walls entertained fewer parishioners, more of whom seemed comfortable breaking the Sabbath for work. Funds to maintain my structure became scarce; the interior was difficult to consistently heat, and the sanctuary seemed to grow hotter and more stifling each summer. There was talk about having me formally dedicated as a historical site, but changing politics, an economic depression, and the collapse of the town’s historical society ceased any further progress. Late that century, the townspeople closed my doors to worshippers for good. I sat empty, dust floating in the sunbeams let in by my tall windows, until I was sold to a wealthy architect who had recently relocated from the West Coast. This man rejoiced over my emptiness, crowed about my potential. This was a project he had always dreamed of, declaring that once it was completed, he could contentedly retire. He added more walls, constructing an entire new addition connecting to the upper part of the sanctuary through an elevated corridor, all with a stone exterior. Bedrooms were located in the upper story of the new addition; the sanctuary’s balcony was now transformed into an open second-story loft to which all the bedroom doors opened. A small rectangular in-ground lap pool was dug into the backyard.

During reconstruction: catastrophe. While skilled, the architect was not familiar enough with the old building materials used in the Hudson Valley. He should have had more than one local inspector check my staircase, more than one inspector who was experienced with both Dutch and Gothic Revival styles, one knowledgeable with its capacity for weight-bearing, and the impact of extreme weather changes on wood. One day during reconstruction, the project about 80% complete, my curved wooden staircase suddenly collapsed in three places, crashing to the floor of the sanctuary in a deafening thunder of splintered wood and clouds of dust. One worker was rushed to the hospital, and the architect was summoned from the city. He arrived at my door in despair, almost in tears. He cursed himself for the ruin of part of my rich history, for the loss of the footsteps which walked up the dark wooden planks, the hands which held the ornate banister now lying in pieces on the sanctuary floor.

The architect eventually finished the job, transformed my walls from that of a house of worship to a house of residence. He rebuilt the staircase and made it sturdier, more modern, and incorporated as much of the reclaimed wood from the former staircase as he possibly could, creating an ornate banister. Though it delayed the job further and added cost, he insisted on keeping the semicircular curve in the staircase. He never did reside in the home himself; instead, as soon as the job was finished, he listed it for sale. The housing market bottomed out; my price dropped once, then dropped again. A young couple, a mathematician and his scientist wife, twin baby boys in tow, toured my walls with an agent, all smiles and excitement. The mathematician and his wife slow-danced; he twirled her around in the empty space which would become their bedroom. The mathematician loved my staircase, exclaimed over the elevated corridor. He had an Italian last name, he mentioned Vasari, mentioned Medici, the Ponte Vecchio, and he had studied in Florence. He was vibrant, charismatic, and magnetic. The scientist wife was quiet, reserved, perhaps even timid, but I felt her observations constantly, felt her eyes studying my walls and all their combinations of styles, knew she thought of all the lives that must have passed in and out of my doorways. Knew she spent time thinking of the years in which I sat empty, the time of the fire, the winter with no roof, when snow fell into the sanctuary and piled up on the floor. What the first Dutch staircase must have looked like, then the second Gothic Revival, and the tragedy of its loss.

I house a family, I provide them with warmth in the winter and coolness in the summer. They are the same, yet changed. The boys are growing, changing from babies to children to young men. The mathematician changed from educator to finance executive. The scientist is trying to change. On paper, she is an educator. The mathematician has frustrations, worries, and resentment. I think, however, that I understand her pain.

If I were asked, I’d tell you she feels more deeply than most other people, that the pain and struggles of the past layer uncomfortably with the pain of being stuck in the present, with no map for moving forward. No joy in watching her children grow; only sadness in grieving their lost babyhood. Feeling more distant from the husband she increasingly does not recognize. Sadness and fear over the perceived distance from her love of science. I believe she feels all the emotions of the lives that passed through my doors, who worshipped in my walls, who joined in marriage, who baptized babies, and closed caskets. If I could talk, I would tell you the scientist carries the weight of all my years.

- The Scientist in the Church - July 15, 2025

- Patricia Drake - January 10, 2025

- The Door - August 8, 2024