Crossed Wires – Direct Line

written by: Mark Woodward

Here we sit—

my wife, Christine beside me,

eyes fixed on the clinic wall,

where sterile light bounces off plastic chairs,

and the air tastes like hospital corridors,

yet the room is quieter than a library after midnight.

The oncologist leans in,

voice calm but heavy,

as if reading from a script of doom,

“Stage four,” he says. “Aggressive. Incurable.”

The words hover, thick as fog,

yet I’m frozen,

stripped down to my socks and whatever dignity remains

after weeks of poking, prodding, cameras inserted

in places polite society doesn’t mention at dinner.

He asks, “Any questions?”

My mind scrambles for polite words—

not “Am I going to die?”—that’s too blunt,

too sensitive for this temple of pretence.

I fumble, dance round the truth,

turn it into twisted riddles,

crossed wires tangling my thoughts

until even the specialist nurses blink in confusion.

My wife watches,

eyes piercing, knowing the script I can’t speak,

the fool I fear I might become

before this sacred council of doctors and machines.

I ask questions that make no sense—

the words crossing like unreliable phone lines,

and the answers come back tangled,

full of medical jargon and hopeful maybes,

but still—no direct line to the truth.

Then, there’s the letter.

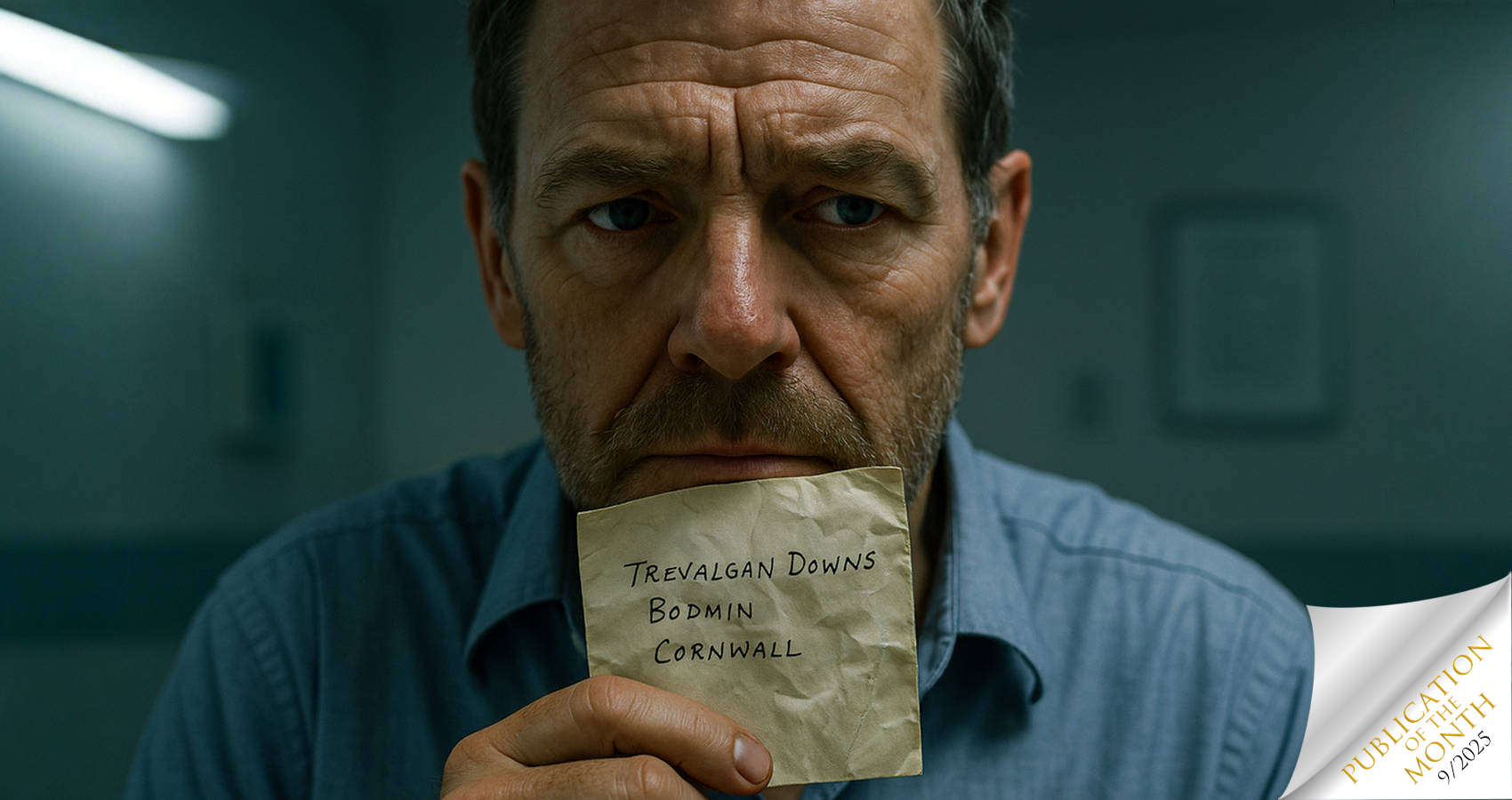

Mark’s Utterly Polite, Slightly Bewildering Letter to Trevalgan Downs Camping Site

(or, How to Ask for a Toilet Without Actually Asking for a Toilet)

Mark— a chap of the utmost British decorum, who’s polished his manners on a fine China-set made of delicate euphemisms — decided to write a letter to Trevalgan Downs, a campsite perched somewhere in Cornwall where seagulls have more rights than humans and the pasties might just be the national currency.

Now, Mark was no ordinary tourist, no. He did not simply say ‘toilet’ or ‘loo’ or even ‘bog’ — oh no, that would be far too plebeian, not to mention shock the locals into a confused frenzy. After a prolonged internal struggle worthy of Hamlet himself, Mark, with the poise of a man tiptoeing across a floor of Lego bricks, landed on the phrase “bathroom commode.”

But even that sounded too brash, too bold. So, with the delicacy of a hedgehog in a tea shop, he delicately trimmed it down to the abbreviation ‘BC’ — a phrase so cryptic it could have been the secret code for a clandestine Cornish pirate society or the name of a particularly aggressive seaweed.

He penned:

“Does the camping site have its own ‘BC’?”

At Trevalgan Downs, Cornwall…

Old Bert Trelawney, the campsite’s bewhiskered custodian, looked at the letter and blinked twice. Bert’s beard was so wild it had its own postcode and had reportedly hosted two nesting owls and a suspiciously jolly squirrel. Bert was a man whose love for a pasty was rivalled only by his confusion at the modern English language.

Old Bert was utterly stumped by this ‘BC.’

“BC?” Bert muttered, scratching his head so vigorously that bits of beard went flying like tumbleweeds. “British Cornish? Bloody Cider? Bodmin Crows? British Council? Bloody Confusion? What in the name of the Cornish cream tea is this?”

He showed the letter to some of his campers, including Gladys from Penzance and Alfie from St Ives, but no one knew what Mark meant.

Alfie from St Ives, an eternal optimist and wearer of dubious jumpers, chipped in, “Could it be the Bodmin Crows rugby team? They’re a brutal bunch; might scare off any unwanted visitors!”

He waved the letter at Gladys from Penzance, a no-nonsense woman with an encyclopaedic knowledge of sheep breeds but zero clue about cryptic acronyms.

“BC?” she said, squinting, “Is that a new dance? They’ve started folk dancing at the Baptist Church in Bodmin. Maybe that?”

“Baptist Church, BC, that must be it,” said Old Trelawny.

In the end, Bert sat down with a pint of stout so dark it could swallow light whole, and composed this reply:

Dear Mark,

I am pleased to inform you that a ‘BC’ is located nine miles north of the campsite — specifically, at Bodmin — which can seat a whopping 250 people at once, which might seem excessive if you’re the sort who likes to go casually. I appreciate it is quite a trek if you’re in the habit of going regularly, but many folk here take a packed pasty and make a day of it. They usually arrive early and stay well past tea time.

It’s a smashing venue, and the acoustics are brilliant. You can hear the faintest whisper, even the normal delivery sounds can be heard. On our last visit, my dear wife and I were so overwhelmed by the crowd that we stood shoulder to shoulder, sharing the experience with a proper Cornish throng.

A supper is being planned soon to raise funds to install more seating — a noble cause, indeed. Should you choose to grace our campsite with your presence, you will find a warm community of friendly locals more than willing to escort you on your maiden voyage to the BC, sit beside you, and introduce you to everyone who matters.

Remember, here at Trevalgan Downs, we’re all about community, and doing it together.

Yours in bewildered hospitality

Bert Trelawney

Trevalgan Downs Camping,

Cornwall

Back in the clinic, the letter sits on my lap,

a metaphor for my tangled questions and awkward truths—

asking for comfort without naming the need,

tiptoeing through language like a tiger in a tea shop.

My body fights, my mind stalls,

but the absurdity — that ‘BC’ might be somewhere nine miles away —

is the joke I clutch, a shield, a secret weapon

against the monstrous seriousness of the moment.

We leave the room,

the crossed wires buzzing still in my head,

but in the distance, that strange letter’s absurd hospitality lingers —

and somehow, in the madness, a trace of hope.

The nurse smiles,

but I see the twitch in her eye —

she’s heard this rhyme before,

the patient who asks in circles,

afraid to say the unspeakable phrase,

the one that would shatter the quiet room

like a dropped plate in a posh restaurant.

“Will I make it?” I try to whisper,

but it slips into a garbled mess,

a tangle of words, hedges, and half-questions

that sound like a crossword puzzle written by a drunk.

She nods, kind but careful,

answers dripping in medical caution,

a polite refusal to say the word ‘death’ aloud,

a duck round the direct line I’m dying to grasp.

So, I laugh—

not with joy, not with relief,

but a laugh that breaks the tension,

like a man slipping on a banana peel

in the middle of a crowded hospital ward.

It’s ridiculous, this fight for dignity,

when they’ve already seen you stripped

to your socks and every private doubt.

I am Mark — the polite man,

the one who writes letters about ‘BCs,’

who tiptoes round the toilet,

who battles the silence by shouting in code,

trying to survive with every broken joke,

each awkward pause, each crossed wire.

Because laughter,

this ridiculous, stubborn refusal to break,

is my weapon, my medicine, my armour —

against a future nobody guarantees.

My wife holds my hand,

steady, fierce, the calm in the storm,

her eyes saying, “You’re not alone.”

And maybe that’s the direct line,

the signal through the clatter of jargon and fear —

the quiet truth in the confusion I won’t say:

Together,

we can face this,

one absurd, polite letter at a time.

The Oncologist clears his throat,

wearing that thin smile,

like he’s just told you the worst joke in the world

and is hoping you won’t laugh at the big reveal.

“You have questions?” he asks,

like he’s handing you a baton in a race you don’t want to run,

but feel obliged to.

And I scramble,

words spilling out like a faulty radio signal,

a scrambled broadcast from my anxious brain.

“Is there a chance, I mean, I know it’s late, but what if…”

No, no, stop. Too much.

Better hedge.

Better circle around the truth like it’s a bunny rabbit on a busy road.

“So, erm, if the treatment doesn’t work, what next?

I mean, how do we plan for, you know, the future?”

Future? The word sticks in my throat,

like a sticky toffee caught between teeth.

They exchange a glance—

a blink, a silent signal in the battlefield of oncology jargon.

The Met Nurse smiles again,

patient, professional,

but her eyes say, “Mate, you’re speaking in riddles.”

I want to shout:

“Can you just say it?

Am I going to die?

Is it soon?

Is it the end of the line?”

But instead, I dither —

around the question,

round and round,

like a scratched record skipping on a vinyl player.

And that’s the crossed wires —

the direct line that never quite connects.

Now, the letter.

Oh, the letter.

I sat with a cup of tea,

thinking, how to ask for a toilet

without actually asking for one?

Because, obviously,

toilet is too blunt, too rude,

not the kind of word you’d hear round these parts.

“Bathroom commode”

sounded like something from a Victorian novel.

“BC” — perfect.

Mysterious enough to cause a national crisis,

but polite enough not to offend.

I wrote:

“Does the campsite have its own ‘BC’?”

Nine miles north, they say.

Bodmin.

Apparently, the BC can seat 250 people,

which sounds like a concert hall,

not a place to quietly disappear when nature calls.

I picture it:

a crowd, shoulder to shoulder,

each person waiting their turn like it’s a jubilee.

Old Bert Trelawney’s beard twitches in confusion,

bits flying like tumbleweed in a desert storm,

or something less dramatic,

like a mild breeze on a Cornish morning.

Gladys squints,

Alfie guesses Bodmin Crows rugby team,

and the Baptist Church folk dancing.

They’re all as baffled as I am.

The reply arrives —

a tour guide pamphlet for bodily functions,

an invitation to a communal pilgrimage,

where nature’s call is a social event.

And me?

I’m still here,

writing letters, asking questions,

tiptoeing around the edges of life and death,

with a smile, a sideways glance,

and a crossed wire or two.

Because if you can’t laugh at the absurdity of sitting in a hospital room,

waiting for words you don’t want to hear,

but need to understand,

…then what’s left?

I sit, socks half off,

legs dangling like a deflated balloon,

waiting for the dreaded camera,

the one that plunges deeper than any nightmare.

My wife beside me,

calm, steady — the rock in this absurd sea of poking and prodding.

She’s seen the socks come off before,

the nether regions invaded with clinical precision,

but I?

I still turn into a shy schoolboy,

a blush creeping up,

even though I know this stage well.

“Any questions?”

The oncologist asks,

eyes flickering with the rehearsed patience of saints.

But I’m tangled in a labyrinth of politeness,

a maze of British decorum,

where blunt words are weapons and softness is armour.

So, I hedge,

“Erm, well, about the treatment… If it, you know, doesn’t quite do the trick…”

The nurse smiles,

like she’s listening to a man ordering tea —

“Just a splash of milk, no sugar — but maybe a mint-chocolate on the side.”

I want to scream,

“Can you just say it?

Am I walking into the dark tunnel or just a gloomy corridor?”

But instead, I say,

“Is there a plan for, you know, after?”

After the battle,

after the first casualty,

after the “if it doesn’t work.”

Crossed wires.

We speak in codes,

in polite riddles,

because the truth is a blunt instrument no one dares wield out loud.

Back to the letter.

Dear Trevalgan Downs,

I cannot, in good conscience, just ask for the loo.

Too crass.

Too direct.

“Bathroom commode” is better,

but still too bold,

so I trim it down to “BC” —

the perfect cipher,

a secret handshake for those in the know.

Old Bert, the keeper of the Downs,

beard wild and majestic as a Cornish storm,

reads my request and scratches his head until small ecosystems form.

“BC?” he murmurs,

“British Council? Bodmin Crows? Bloody Confusion?”

The campsite community gathers —

Gladys, a sheep breed encyclopaedia,

Alfie, the eternal optimist with questionable jumpers —

none have a clue.

So, they send me this epic saga,

a pilgrimage nine miles north,

to the hallowed halls of Bodmin,

where 250 seats await those answering the call of nature.

A social event, no less.

A place to share the experience,

to make a day of it.

It sounds less like a toilet, more like a festival.

And here I am,

still navigating the absurdity of it all,

waiting for the ‘direct line’ to connect,

hoping for a moment of clarity in the mess of crossed signals.

Because survival isn’t just about treatments or diagnosis —

it’s about finding laughter in the gaps,

smirking at the ridiculousness,

and writing letters that say “BC” instead of “toilet.”

It’s about standing tall, even if your legs feel like jelly,

and making this strange, cruel journey a bit more human —

one polite, baffling, hilarious step at a time.

So, here’s to crossed wires, tangled lines,

to polite puzzles and cryptic codes,

to socks half off and whispered truths,

to “BC”s that turn into pilgrimages,

and laughter – uninvited but essential –

the only proper medicine left in the cabinet.

We survive not despite the madness,

but because we find the humour in it,

and wear our bafflement like a badge,

marching on through storms of silence,

armed with nonsense,

and the stubborn hope

that somewhere down the line,

the signal will clear.

Until then,

we write our letters in riddles,

sit in waiting rooms like reluctant monks,

and keep holding tight to the small absurdities

that make us human —

the only true direct line to life itself.

- Spotlight On Writers – Mark Woodward - January 3, 2026

- Breakfast on the Beach - November 30, 2025

- Crossed Wires – Direct Line - September 4, 2025