Paper Ashes

written by: N.T. McQueen

@NTMAuthor

She did not remember the stories her father told at night, despite his claims he tucked her under his arms as he recounted their family’s journey. The escape from Hanoi, burned and ashen, how they hid under the burnt corpses of their neighbors until the engines faded, and the month at sea on a barge, stowed in the belly of a cargo ship behind crates of sulfur. He described the sinew of rat and how they had forgotten how daylight felt. Her older brothers nodded, brows heavy with memory. She caught herself almost letting her head move with theirs and stopped.

Chenda waited tables and lacked the ability to recall a time when she had not. She rarely entered the kitchen, but always heard her brothers’ voices call out orders and filthy jokes in Vietnamese among the clang and clatter of woks and spoons. She blushed at their crudeness but the patrons ate their Chow Mein, Orange Chicken, and Mu-Shu without offense. The oily stench gagged her and she fought the urge by holding the dishes at her waist. Her father forced her to wear her long, black hair in a bun despite her wishes. When she was younger, she had confronted him on this behind the counter and her father left bruises the shapes of fingerprints around her bicep as he growled his displeasure at her lack of respect. Her mother listened at the register, eyes down, and silent.

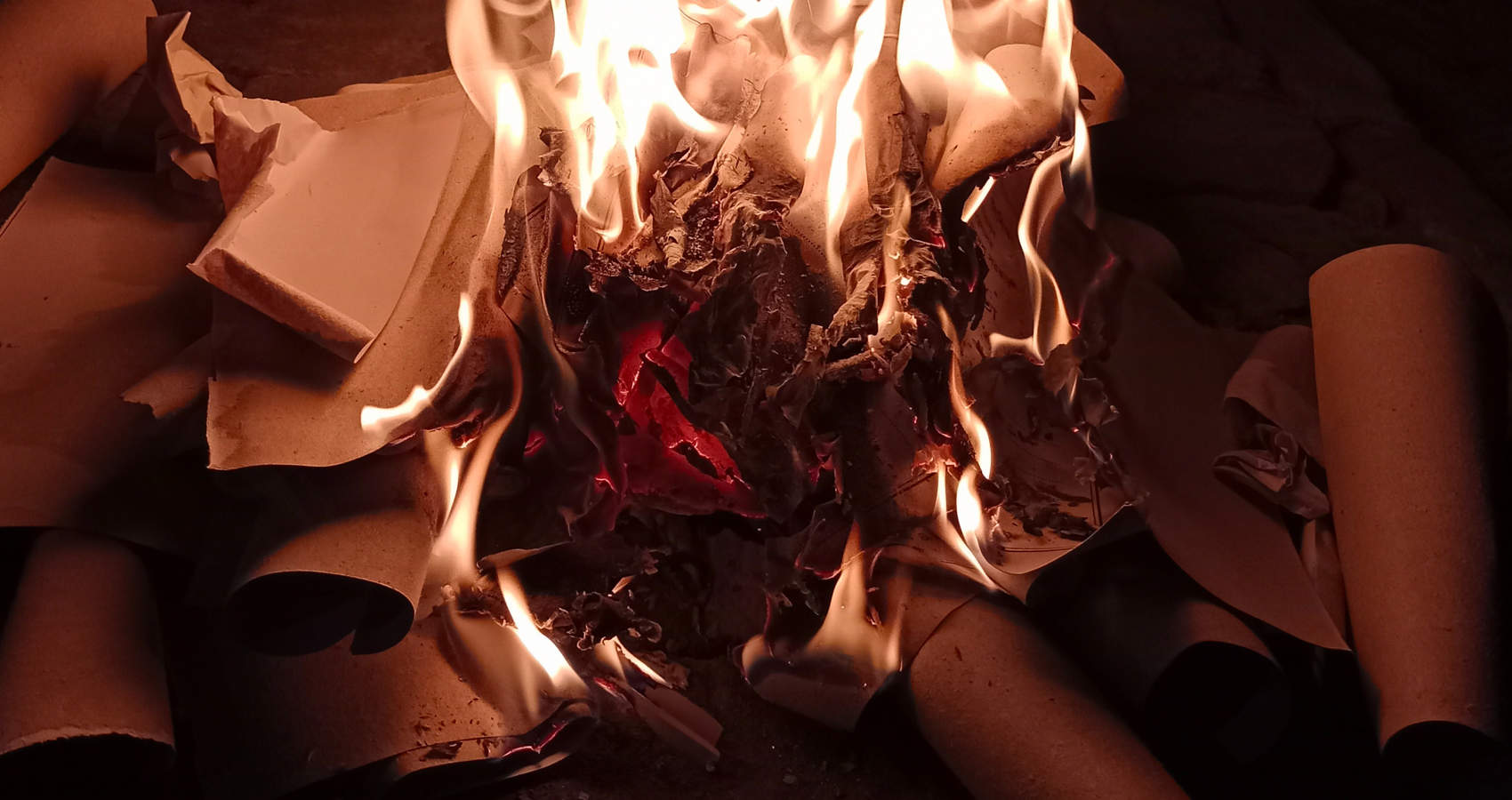

Since she could remember, her family had always been Chinese. Her father’s skill at his culture’s cuisine failed to thrive in Port Lake. Bún măng vịt, Cháo, and Nem Nguội repulsed patrons once the plates steamed before them. Grizzly vets from the war scratched “gook” across the glass doors and relieved themselves on the mat. Her father, after a week of drink, denied his birth name and adopted the surname Yi. He took a hammer to the sign and burned the menus in a barrel behind the restaurant and decided to reopen the restaurant and serve the Chinese food other local restaurants provided. The kitchen moved with industrial constancy and churned out plate after plate as the familiar emptiness of the tables disappeared. After several weeks, Chenda informed him that they had not changed the décor to Chinese, but he only shook his head and returned to the kitchen.

Her accent defined her at recess, prompting imitations and mockery from the other students with fingers pulling at the corners of their eyes. She lingered in the classrooms until the children returned to class and the electricity inside her ceased. Though attentive, her teachers spoke slowly and exaggerated to her, gesticulating as if playing charades with the deaf. Over time, she suppressed the trace of her accent by watching Saved by the Bell and Full House. Her brothers often intruded upon her lessons and denigrated her for her shame at watching stupid American fantasies about family. When she waited for the school bus in the mornings, she could hear their fake American voices shout clichéd phrases from the apartment window above the restaurant, followed by boisterous laughter.

Despite the eradication of her accent, she roamed the fringes of the frenetic schoolyard, kicking a sole piece of gravel that clattered ahead of her steps. She excelled at her studies and usually was afforded free time while the others worked. Her delicate fingers would draw fluidly and precise along the edges of the notebook paper. Small sketches of the immediacy around her. A piece of chalk, a crescent sandwich bag, a boy with a ballcap. When the pencil graced the page, she imagined how a duck glides across the water, suspended and graceful how the water can hold you weightless. She used a pencil a day.

Though adolescence had come to her, she still shared a room with two of her brothers, both only months younger. The image of her body sickened her and she refused to face the mirror before and after she showered. She wore sweatpants and baggy shirts around them. At night, when they assumed she slept, she listened to their talk of women and coiled the sheets around her head and begged for sleep. The gawky nature of her new body terrified her and the looks it attracted from others at school burned across her. In the summer, she wore jackets and shirts that trailed below her waist. In the crowded halls, prurient hands scrambled at the cloth, searching for what lay beneath. She pressed her Algebra into her chest until those spiteful fingers remained behind her.

She drew in relentless binges, absconding food until her hand resembled bark. Pencil shavings and stacked paper cluttered her corner. Sweat-stained yellow around the grey collar of her shirt. She often fell unconscious onto her bed until her father grabbed her arms and shook her awake. His round cheeks and nasal command to get to the restaurant rung in her ears. He paid no mind to the stacks of paper and the smell of wood around him. Behind the kitchen, a rusty, black barrel that her father burned menus in, she also burned the images of her mind one piece at a time. The flame licked at the gutters and the stench of frying oil flowed from the kitchen. She watched until the last blackened pieces drifted through the grate and rode the breeze above the restaurant and she marveled at their effortless flight in death until they had ascended beyond her vision and grasp. Then she returned to her tables.

Her reclusive nature defined her adolescence into high school. She imagined herself a fly and often thought she heard buzzing when she walked. Often unable to ignore her secret desire to one day use those phantom wings to take flight. When the linemen bumped her with their puffy-sleeved jackets, when their deep voices named her a “Chink Bitch,” she tensed her back in futile dreams. Her life between the classrooms moved slowly. Only at the back of Mrs. Grayson’s beginning art class did she breathe. Her hand glided and released through her lectures and she drew the wings she desired.

Her sophomore year, between Geometry and U.S. History, a hulk of a figure smacked a thick-fingered hand across her books. She bent without protest, as if in a bow, and gathered the loose drawings and worksheets scattered around her. Near her hands, two delicate shoes stopped. When Mary spoke to her, she felt the words were intended elsewhere and failed to respond. It was when Mary laughed that Chenda raised her eyes. They gathered the papers together and walked together since then. From eight in the morning till three in the afternoon, the two met at each other’s lockers and walked to their classes until separation became a necessity, Chenda often remained reticent while Mary’s bell-like voice spoke as if the act were destined to soon vanish. Chenda smiled, her books pressed to her chest, and floated on Mary’s words.

When she returned home, the clouds she rode disappeared and she worked with the clatter and boisterous tongues behind her, placing fried rice and egg rolls before bloated white people. Her brothers had slowly plumped from the food of their hands but Chenda refused to eat what they made. The derision she received she shelved with the rest of her life. She even bathed after work, scrubbing her hair and skin with such vigor, she emerged red and soaking from the shower. Her mother combed her hair each night since she was a child, silent and with long, steady strokes of the frayed brush. The only sound came from the brush. The bristles on Chenda’s scalp caused her muscles to weaken and she lingered between the living and the dead, gracious to be a ghost of twilight.

The summer of her junior year, Mary invited Chenda to the County Fair. Since she had worked all summer, she asked her parents as a good child but they refused. When she questioned their decision, her father slapped her across the mouth. She held her lips and glared at the top of her mother’s head. Her anger burned so fervent she hoped to singe the crown of her mother’s head but she would not face her daughter. She had ceased to listen to her father’s lecture and had eyes only for her mother’s submissive figure, passive and distant. A fierce desire to shake her overtook Chenda and, unable to repress the jeers of her brothers and the hands of her father, she gripped her mother’s frail arms and shook her like one shakes a tree for its fruit. Choked shrieks escaped from her as the violence overtook her. Her father’s harsh yells caromed from her blind walls and she wondered if she could stop. Hands grabbed her body and yanked her to the floor. The black eyes of the men looked down at her and, in those vacant eyes, she saw shame glisten. Their denigrating voices clamored against her, cursed her as a spoiled American and she sprung to her feet and locked herself in the bathroom. With her clothes on, she sat with her knees at her chin in the tub and the roar of hot water drowned out those voices at the door.

The next morning, while her brothers slept, she reached under her mattress and retrieved the bulging, sloppy portfolio of her sketches from the summer. She tiptoed down the whining staircase and outback to her barrel. The morning fog, crisp and bitter on her fingertips and ears. She slipped the matches from her sweats and the gallon of cooking oil from the kitchen. All night, a hopeless melancholy had plagued her, but, before the barrel, she hated herself for feeling nothing. She dumped her imagination into the barrel and she averted her gaze from the faces she had placed there. She smelled smoke but had not lit the fire yet and, horrified, she saw a figure under the eaves. The lithe man leaned against the stucco, an ember jutted from his mouth, and he watched her. She looked down as if she had been caught in a shameful act and watched him from the corners of her vision. He said his name was Larry and he asked her what she was burning but she could not answer. Slinking from the wall, he swayed over to her and paused at the barrel. Gazing, he reached down and lifted a sketch of an ancient man reading a newspaper. He pondered the image a moment, light mist gathered on the bill of his ball cap. His blue eyes affixed to her work and she floated into his eyes, a reveling she had neither expected nor wanted, yet behind his gaze she felt witness to herself. As if satisfied, he nodded and asked if he could keep this one. She nodded. He offered a silent smile, a hesitation, and then walked away, folding the paper into his back pocket. Her eyes followed him until he had long left her sight. She weighed the matchbox in her hands as if on a scale before slipping it into her sweater pocket.

That last week of summer, she did not sleep, but, rather, lived nocturnally with cramped hands and the smell of pencil shavings. She drew his face from memory and it remained from drawing to drawing. With each new image, she could not decipher where reality and memory collided. The nag of her brothers and the putrid oily food she placed before patrons could not affect her. While working, she checked by the dumpster and barrel every hour, but the only soul she found was Oney and his trash bag of cans. After Labor Day, she arrived at school full of electricity. She searched for Mary between classes but learned through eavesdropping she had not come to school. Her new secret burned within her and her eyes frequented the mounted clocks until three o’clock. She snuck onto a different bus that took her toward the hills and walked toward Mary’s home. The summer heat bore down upon her covered body as she traversed the long, concrete driveway to her front door. Her bangs clung to her moist forehead. She rang the doorbell but Mary’s mother answered solemn. When Chenda asked if Mary was alright, her mother frowned and, with an indifferent examination, replied that Mary wasn’t feeling well and closed the door with only a soft click. Chenda walked heavily the hour trip to the restaurant. A wearisome burden accosted her and the inescapable blame dragged at her sneakers until she approached the bustling restaurant after dark. Due to business, her parents and brothers did not notice her absence.

For three days, Chenda waited for Mary at school but she did not appear. By Friday, her desire to voice Larry into being had waned and she, once again, had become her old apparition. She felt she had become like the old stories her father would tell after he drank. Her legs dangled off his lap while one strong arm wrapped around her waist as he spoke of how spirits still roam the earth but are only seen by those who have the care to see them.

She checked every day in the early morning but never saw him. Once, she brought some recent drawings and burned them without taking her eyes from where his shadow last stood. On the following Monday, Chenda spied Mary in the bathroom during second period. She opened her mouth to speak but, in the mirror’s reflection, she saw Mary’s eyes and words retreated back into her. In the grey-walled room, Mary leaned against the running sink, watching the water pour from the faucet. Chenda lingered near the doorway, the water’s hiss echoing around them. Though Mary’s eyes remained still, Chenda felt her friend broken and would not allow herself to hold her, would not allow herself to speak Larry into being. They stood divided yet connected in the chill until Chenda turned, washed in sunlight and Mary faded into memory.

She returned to loneliness. The hours between classes moved like dying clocks. She no longer looked behind the restaurant or burned her sketches, but placed the charcoal and pen to paper with a fervency she had never harnessed. Daylight signaled the end and she placed her instruments down crudely with crippled fingers. She stored the papers under her mattress and, by Thanksgiving, she could not lay on her bed for its wave and crinkle. She had ceased to speak and used her eyes to communicate with patrons, sometimes to ill effect. But the locals often reciprocated her silence with their own. When her parents provoked her to speak, she closed her eyes and stood still until their voices were drowned by the silence.

She dreamed in circles. The next two years passed in routine and she began stashing her papers around the house. In dressers, under rugs, folded into her clothes, even taped under tables in the restaurant. Her dull eyes became encased with soft bruises and her neck tensed. Her thoughts of Larry turned rancorous and she abhorred his impact upon her life. Her graduation loomed but when she drew her future, she only drew woks and lotus flowers encased by a great wall. Sometimes, unable to sleep, she would lay awake and try to remember her lost name while her brothers snored around her. Her liminal dreams she walked the trace of her name like a maze, within it but too close to read. In those dark hours under the intrusive streetlight, she examined the point of her pencils and wondered if she could write herself upon her own soul if she simply pushed the pencil through the skin, the muscle, and body and she delicately touched the skin between the tendons of her wrist and press until she felt something. But, morning always came.

In June of her senior year, she no longer could draw her future and the impulse to write upon her soul consumed her mind. Each night, she sat below the streetlight that poured into her window and sharpened the end of the pencil but never placed it to her skin. She began breaking a pencil each night and leaving the remains atop her mattress to remind her. The date of her graduation glowed red on the calendar and she refused to read it. Bitter blood trickled through her veins and those dark thoughts filled her head like an insidious fog.

On the night before her graduation, she had resolved to write on her soul. With meticulous inspection, she had chosen the pencil with which to do it and held slight guilt for how her family would hate her for disgracing the family.

After the restaurant closed, she hung her apron and walked up to her room, knowing her brothers would be busy cleaning the kitchen. The steps stretched never ending and the soft footfalls seemed thunderous. She entered her room and went to retrieve her pencil. But she could not find it. When she searched by her mattress, she found her pencil but also discovered an envelope addressed to her in her mother’s childish, handwriting. The paper weighed in her hand and she feared what may be released should she open the seal. She glanced from hand to hand a moment before placing the pencil and tearing the seal of the envelope. She removed a letter written in Vietnamese with two thick, bound stacks of hundred dollar bills, and a bus ticket. Her eyes blurred and focused holding the bills and saw herself in her room, and almost chortled at her own face. She unfolded the letter, releasing another paper that fell next to her feet. She bent to retrieve it and saw a formal letterhead for the Academy of Art in San Francisco. Though the dark clung around her, the streetlight illuminated all she held. She stood slowly, reading the letter in her mother’s handwriting. She read those careful words with such repetition, they created their own melody as the salty tears blurred the last words.

The following morning, before her family awoke, she crept down the stairs with only what she could carry and stepped into the red dawn. The air felt afire, so much that she believed she could smell smoke. She followed the directions in the letter and told no one. The sun, blood red, rose above the smoky hills as she walked to the bus stop around the corner. In the smoke, she thought she saw his face form and she smiled, clutching her backpack.

The bus arrived as stated on the ticket and she handed the simple piece of paper to the rotund driver. The solemn faces glanced at her before returning their eyes beyond the reflections in the glass. She tapped the leather backs of cracked seats until she reached the back of the bus and slid toward the window. Her reflection flicked from the window in return as the glare distorted buildings and faces and the lake as the bus moved. She welcomed the force of motion and clutched the folded note of her mother’s handwriting and the name given at her birth scrawled in her language, pressed firmly against the blood in her veins, pressed close to her heart.

- Spotlight On Writers – N.T. McQueen - January 6, 2024

- Faces in The Flame - November 12, 2023

- Lower Lights - May 11, 2023