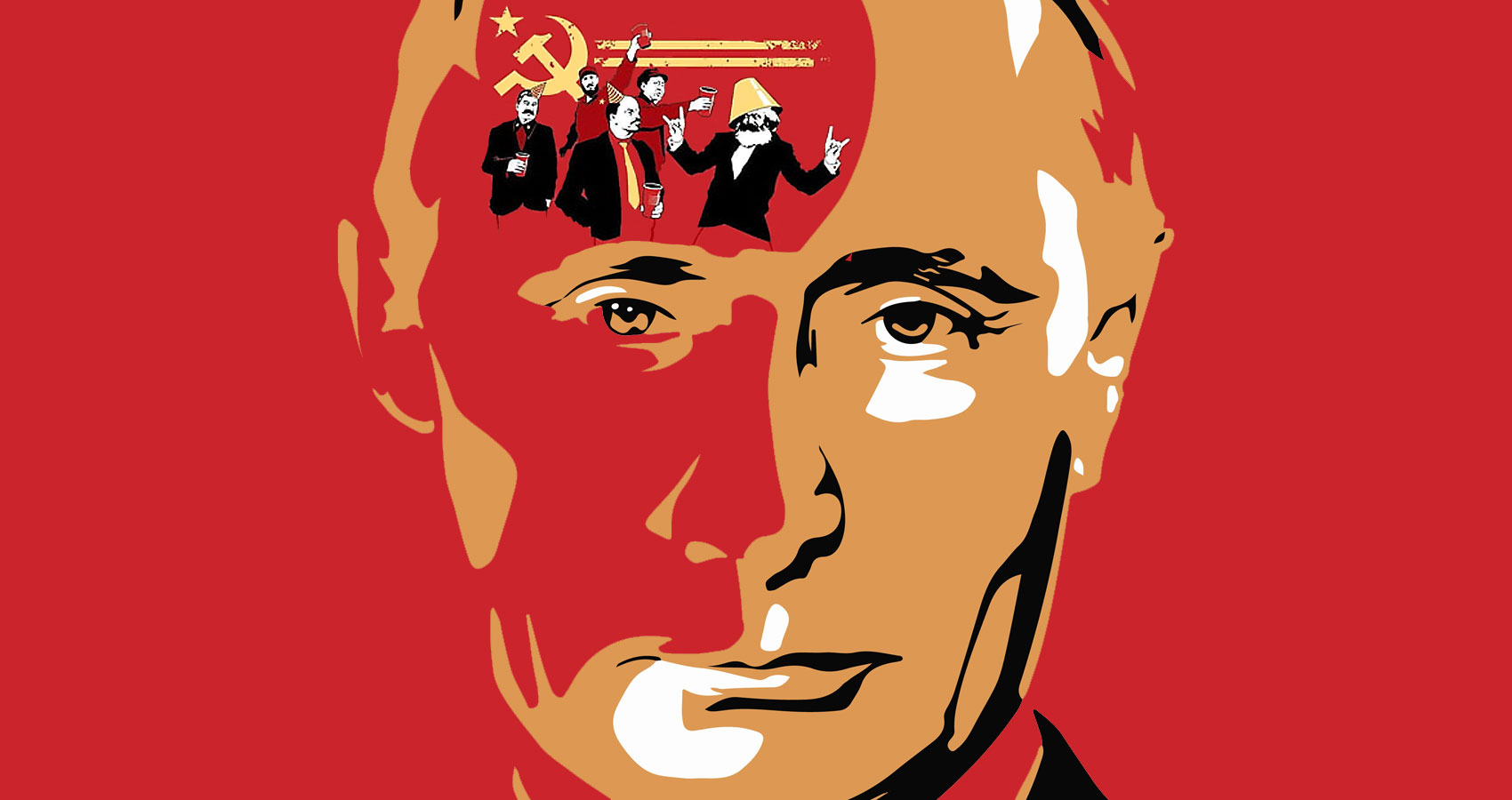

We Still Have Putin

written by: João Cerqueira

Stalin was outraged. Mankind had accused him of being a dictator, a murderer, a psychopath, and worse still, of having a ridiculous mustache. But he was no longer able to lock anyone away in a gulag, deport them to another country or stick an ice pick in their head. Because now he was no more than a ghost. And even if he could return to earth, he wouldn’t scare people any more than when he was alive. No one would die of fright if they saw his apparition and heard his voice calling from the other side.

So he vented his frustration on Lenin. “Why is it that men are so ungrateful? I used to be the father of the people and now I’m an executioner? Who was it that ruined my reputation? That creep Nikita was one of them but there must have been more comrades who betrayed me. I should have had them shot.”

“Comrade Stalin, how many times have I told you that that’s not the way to solve your problems?” Lenin scolded. “Some people should be shot, obviously, but there’s no need to get carried away. Half a dozen comrades you don’t get on with anymore and one or two fools causing trouble are more than enough. That stops everyone from challenging socialism for a while. Killing everyone now, without any rules, just can’t be done anymore, comrade. It doesn’t look good. Scientific socialism sets out rules for everything; shootings can’t be an exception. And if we even kill our friends, who will trust us?”

“My secret police, the NKVD, did an excellent job. Why did they get rid of them? The KGB? Did you ever see them make a serious purge?”

“The KGB doesn’t even exist anymore, comrade,” Lenin lamented.

“The world has gone mad. Where will this all end?”

“We still have Putin…” replies Lenin.

At that moment, Marx intervened. “I’m sick and tired of this conversation. You’re both idiots who stole my ideas and ruined everything. First of all, I stipulated that a classless society could only be built in an industrialized country, England for example, and never in a land of peasants such as Russia. And secondly, I never ordered anyone killed, with or without rules.”

“Watch your tongue comrade Marx,” Stalin said. “You’re lucky you’re not alive anymore, or else …”

Marx challenged him. “Or else what? Get someone to kill me too, would you?”

“Calm down, calm down,” said Lenin. We are all comrades and we still have the same common enemy: capitalism. Though I think they may call globalization nowadays.”

“I’m not that kind of comrade,” protested Marx.

“Ah comrade, you never stopped being a Jewish bourgeois,” said Stalin. “You, who never lifted a finger in your life, you could really do with spending a few years in Siberia. Kill you—no, I wouldn’t kill you. But I would re-educate you through hard labor for the rest of your existence. Believe me, half a dozen years with a pickaxe in your hand, digging holes in the ground, forty degrees below zero, some good beatings in prison, starvation, and you’d soon see how you would end up writing a new manifesto, this time praising me.”

“You miserable wretch!” cried Marx.

“Are you going to call me a murderer too? Look, if you’d never written your theories in the first place, no one would have probably ever heard of me. Like it or not, I am one of your children,” said Stalin.

“I disown you,” Marx answered.

“Like you did to the servant’s child?”

“You miserable rascal!” yelled Marx, approaching Stalin.

“I already said that’s enough, now,” said Lenin, placing himself between them.

“And you’re not much better than him, no sir.” Marx turned on Lenin. “You led the revolution on behalf of the people, you overthrew the tsar and then you proceeded to be the new despot. I said dictatorship of the proletariat, not a one-man dictatorship. Can’t you read in Russia? Is it because of the vodka?”

“Don’t you see, comrade? This Jew really hates us,” said Stalin. “What he can’t deal with is the fact that we had the courage to do what he didn’t. Writing theories to change the world, any lunatic can do that. But risking life in a revolution, not everyone can do that.”

“Come to think of it, why don’t we have any vodka here?” asked Lenin.

“Good question, we haven’t toasted to the revolution in ages,” Stalin lamented.

“It’s part of your punishment,” said Marx, smiling.

“And what is your punishment, Jewish comrade?” Stalin asked.

“Being in your company,” replied Marx.

“Look Stalin, seeing as we’re talking about the past, there is something that I’ve been wanting to ask you for ages,” said Lenin.

“Really? What, exactly?”

“Some people have said that before the revolution you were a double agent and that you used to pass the information on to the tsar’s police. Is that true?”

“Pure slander. Do you see now how important it is to kill our enemies?”

“How many did you have killed, actually? Did you lose count?” Marx asked.

“The question, comrade Jew, is poorly made. The question shouldn’t be how many I killed but rather how many I freed from servitude around the world. And the answer is billions. Billions, comrade Jew.”

“Yes, that’s true,” said Lenin. There were some excesses, as happens in all revolutions, but we brought hope and peace to mankind.”

“While he”—Stalin gestured toward Marx— “spent his life speculating on the stock market and impregnating servants, without caring a jot for the disadvantaged.”

“You miserable scum!” cried Marx.

“So it isn’t true that you were doing exactly the opposite of what you were preaching? You criticized capitalism and at the same time invested in shares. You denounced the exploitation of the proletariat and bourgeois depravity but took advantage of the workers who depended on you. You were no better than a hypocrite,” said Stalin.

“Shall we talk about the Holodomor famine?” blared Marx.

“What’s your problem with it?”

“What’s my problem, you rascal? You stole grain from Ukraine and you left five million human beings to starve. That’s my problem.”

“Statistics, Jewish comrade. Wasn’t it you who said that the state should appropriate the means of production? That’s just what I did. I put an end to feudalism and serfdom. No owner would have a profit ever again. The problem was sabotage. Sabotage of the agricultural production, probably made by people of your race.”

“Rascal,” grumbled Marx.

“I already told you both to end this discussion,” said Lenin.

Marx snapped back. “You keep your trap shut, we’re going to see this through to the end.”

“You see, comrade?” said Stalin. “He only sees bad things in socialism. He doesn’t even recognize the merit of his ideas. Hitler, despite his faults, was a much more reasonable person. You can’t discuss anything with this guy.”

“Oh come on, comrade Marx,” said Lenin, “don’t be like that. Why the hell are you always criticizing us? We’ve already admitted that we made some mistakes—”

“He hasn’t admitted anything,” interrupted Marx.

“Fine,” said Lenin, “but you have to agree that when you fight for a greater cause these things happen. The means justify the ends, don’t you agree? This is that dialectical process that you invented: thesis, antithesis, synthesis. The thesis is the socialist project, the antithesis is the mistakes made, an unnecessary shooting here or there, and the synthesis is the future communist society without exploiters or exploited.”

“And where is it?” Marx demanded.

“Well comrade, you predicted the downfall of the capitalist system, but the only thing that fell was the Berlin Wall. History’s march towards progress went out of kilter. Can you explain to us why your theories didn’t come to fruition? There must be something wrong, don’t you think?” asked Lenin.

“My theories are absolutely right. They are scientific—”

Stalin interrupted him, turning to Lenin. “He never understood any of this. He never lived with his feet on the ground. It was because they listened to all your nonsense that so much misfortune happened. Thesis, antithesis, synthesis? A Kalashnikov has all the dialectical materialism it needs to educate the masses.”

“It’s your fault that the capitalist system still exists. With your brutal methods, with your paranoia, and your pathetic cult of personality, you turned the working masses away from socialist ideas. They prefer to be exploited to clenching their fists. The class struggle is over, thanks to you. You, Stalin, are the gravedigger of communism.”

“He had to make his mark. He had a difficult childhood; his mother put him in a seminary,” said Lenin.

“Hey! I don’t need you to defend me.” cried Stalin.

“A comrade is duty-bound to defend another comrade,” said Lenin.

“A comrade is duty-bound to attack those who attack other comrades,” Stalin corrected.

“And that’s just what I did.”

“No comrade, you defended me and what you should have done was attack that Jew there.”

“I am very proud to be Jewish,” said Marx.

“Why didn’t you become a banker? That’s what Jews are: bankers, traders, moneylenders. In short, capitalists. When you start doing things that you’re not meant for, that’s when the problems begin,” said Stalin.

“There it is,” said Marx, pointing his finger at him. “There you have the proof that you never understood the classless society project. Leaders of the classless society do not discriminate against people because of their ethnic origin. Proletarians of the world are equal. But you, you reveal all the racial prejudices of capitalist society and of your friend Hitler.”

“He has a point, Stalin, you shouldn’t call people Jewish. Some Jews aren’t that bad,” Lenin said.

“Trotsky?” said Stalin, hardly stifling a guffaw.

“And let me tell you, there are Russians who aren’t that bad either, but that can’t be said of you or of your colleague Putin,” Marx retorted.

“I’m not Russian, I’m Georgian,” said Stalin.

“We’re all Soviets,” Lenin corrected him.

“I’m German,” Marx said.

“And, by the way, what do you have against Putin, comrade Marx?” Lenin asked.

“What do I have against Putin? He has invaded countries, arrested opponents, silenced the press, and worse still, he has become a capitalist.”

“Comrade Marx, let’s analyze the situation in a dialectical manner. Comrade Putin took power at a very difficult time, after that traitor Gorbachev had chopped up and sold off the USSR. Comrade Putin is not a capitalist. Comrade Putin is in a process of antithesis against bourgeois democracy to try to restore the greatness of the USSR. This takes time; there are many enemies, many saboteurs, but he is on the right track. Finally, Europe is afraid of a Russian. Who would have known that gas could be the weapon of the future?”

“It was well used in the past,” Stalin joked.

“Comrade Putin is our last hope. Fidel Castro is finished, the Chinese are traitors, that guy from North Korea should be in an asylum and that Venezuelan one too,” said Lenin.

“Putin is very soft. He doesn’t have the courage of a true leader. Why doesn’t he open a gulag as he should do?” Stalin asked.

“They’re not called gulags anymore, comrade,” explained Lenin.

“And purges, how many has he done?” Stalin asked.

“He has purged some journalists and a few entrepreneurs.”

“That’s not enough. Sometimes I doubt if that Putin really admires me…”

“He admires you comrade, but for the moment he can’t say so in public,” said Lenin.

“Why not?”

“He’s not powerful enough yet to confront the Americans,” explained Lenin.

“So the only place I’m still honored is Korea?”

“Comrade Stalin, in North Korea no one knows who you are anymore. Everyone there believes that the world was created by the Kim dynasty,” said Lenin.

“Even they betray me? Well, drop an atomic bomb on them, then,” said Stalin.

“I’m liking Russia less and less,” Marx commented.

“Whose side would you be on if you were alive during the Second World War, Jewish comrade?” Stalin asked.

“I would be against tyranny, the Holocaust and the gulags,” replied Marx.

“What is that supposed to mean?” asked Lenin.

“I was very clear; I would be against the tyrants,” said Marx.

“Which tyrants? The good ones, protecting the people, or the bad ones, who defended the exploiters?” asked Lenin.

Stalin intervened. “Do you see, comrade Lenin? Jews mince their words; they hide their intentions; they cannot be trusted. But this means that you would be against us.”

“Against you, yes, and in favour of the Russian people,” Marx replied.

“Comrade Marx, that’s a guileful answer. You shouldn’t abuse the dialectic. Don’t you think that a little self-criticism is in order, after so much criticism directed at us?” said Lenin.

“Jews only criticize themselves in concentration camps,” said Stalin.

“You see? He’s just the same as Hitler,” Marx said to Lenin.

In the meantime, someone appeared and whispered into Lenin’s ear.

“Hey, I have good news: Putin has invaded Ukraine.”

“Really?” Stalin asked with a twinkle in his eye.

“Yes.” Lenin was beaming. “Crimea is ours again. Didn’t I tell you that comrade Putin could be trusted?”

“And how did the Europeans react?” Stalin asked.

“They are really scared, paralyzed with fear.”

“Excellent. Without Churchill they’re not going anywhere,” said Stalin.

Lenin continued. “The Europeans won’t do anything for two reasons: firstly, they have no armies; secondly, they would lose big business.”

“And the Americans? They’re always against us,” said Stalin.

“Don’t you worry. The Americans don’t know what to do either. They have enough wars already,” said Lenin.

Marx intervened. “You both seem very happy, but you’ve forgotten the Chinese.”

“The Chinese, comrade Marx, like invading countries. This time they’re on our side,” replied Lenin.

“I have to admit, I underestimated comrade Putin,” Stalin said. “He has leadership qualities after all. Has he already begun deporting Ukrainians? And when is he invading Poland?”

“Let us hope. Comrade Marx here wrote that history repeats itself,” said Lenin.

“First as tragedy, then as farce,” Marx clarified.

“You’ve got it wrong once again, Jewish comrade. Don’t confuse your life with the history of people. My instinct tells me that something big is about to happen. Comrade Putin, I am sending you a hug from down here in hell,” said Stalin, stroking his mustache.

- Perestroika: An Eye For An Eye, A Tooth For A Tooth - February 10, 2024

- We Still Have Putin - March 3, 2022