The Old School Room

written by: Sarah Das Gupta

The door of the old schoolhouse slammed shut. Odd- there were no draughts in the deserted corridors. Outside the skies were overcast. There was a sullen stillness even the trees in the silent playground seemed to be drugged by the heavy air. The classrooms were so much smaller and airless than when I had sat in one of the antiquated desks so many years before!

I squeezed into the seat of one near the back of the room. The wooden top was covered in ink stains and scarred with names and initials from generations now lying in the churchyard nearby. ‘Sawbone’, ‘Gibbons’, ‘Dalton’, ‘Geddings’, village names on the graves, on the war memorial, and here on the desktop. I opened it automatically, half-expecting Miss Dunne’s voice to bark out the usual reprimands. A battered exercise book lay in the corner. ‘Michael Owen’, the name had been inscribed in childish scrawl. On the first page was a diary for – the 6th of January 1947. Michael had struggled to write one sentence. After several false starts and alterations, he had managed to record, ‘It was snowing hard today.’ I pictured the bottles of milk lined up to thaw in front of the heavy Victorian iron stove. Rows of small Wellington boots in the corridors. Platoons of snowmen on the school common.

As I sat daydreaming, the unmistakable sound of children’s voices drifted into the room. The sound hovered and echoed in the wooden rafters of the ceiling. I followed the singing, out into the corridor. It seemed to be coming from a classroom on the right. The door was blocked by a pile of builders’ rubble.

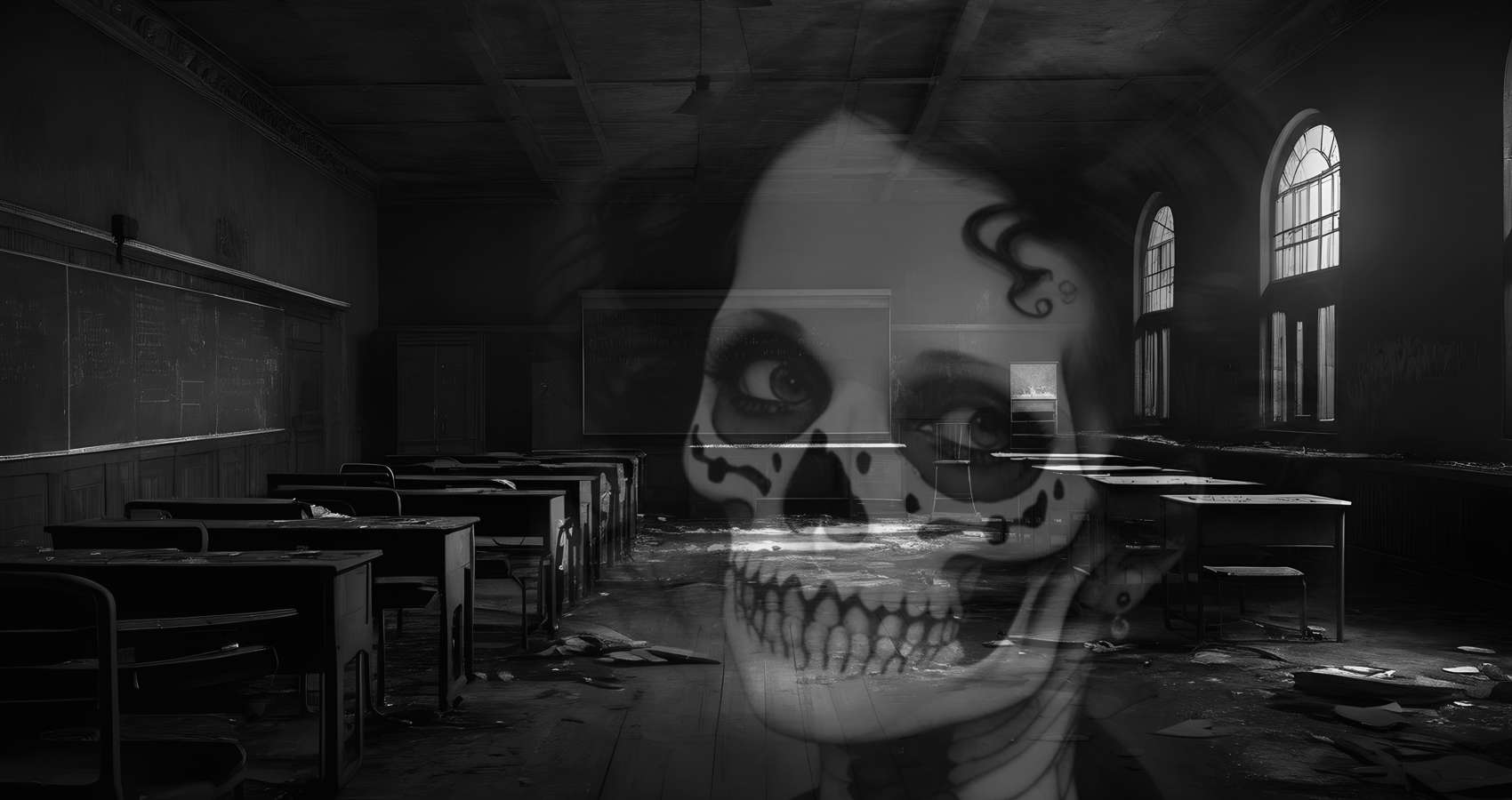

As I stood listening, I could hear the high-pitched voices singing. The pile of broken bricks had gone. The classroom door was wide open; bright sunlight streamed in through sash windows. Children sat crowded into rows, their backs to me as I watched. The song was an old favourite of the Great War, ‘It’s a long way to Tipperary.’ Some stumbled over the words but joined in nevertheless. In the front of the classroom Union Jacks were hanging, the red, white, and blue colours blazed in the sunlight; Lord Kitchener’s face glared down from the famous recruiting poster, declaring, ‘Your Country Needs You.’ The teacher, busy conducting the singing, looked elegant in her long black skirt which brushed the floor as she walked. She moved between the rows of desks towards the back of the room. It was as if I were invisible. She was only a few feet away but seemed oblivious. With a sudden shiver of horror, I understood why. Her empty eye sockets, in a thin, white face, were unmoving, as if fixed on some distant ‘vision.’ I walked up the side of the room and turned to look at the class. The faces were expressionless. Empty sockets ‘looked’ ahead. Thin, parchment-like skin was stretched so tightly over the faces that the bones of the skulls were visible in the sunlight. This was a classroom of the dead!

Suddenly, behind some desks, dark, uniformed figures were standing. Some were covered in mud from the trenches, some had gas masks, hanging loosely from their necks, some had limbs amputated, some shook uncontrollably. All were maimed and eyeless. Names had been pinned to their backs, ‘Geddings’, ‘Dalton’, ‘Sawbone’, ‘Gibbons’, those familiar names. The name on each figure was also written on the front of the exercise book on the desk – a roll call of the Glorious Dead.

A bell rang loudly. I was standing then in the old, familiar playground. Here, I recognised children I had known. They ran past without a second look! For them, I was simply invisible. The girls were skipping over a heavy rope being swung by two of the teachers. One dark-haired girl looked different. As she skipped towards me, I saw the same empty sockets, the same paper-thin skin. I remembered she had died in the classroom one brilliant June day. We had made ‘pea-shooters’ out of the hollow stems of a common wild plant, hedge parsley. It was one of those games village children have played for centuries. In the excitement of the moment, she had sucked, instead of blown! The pea had stuck in her throat. She had lain on the floor of the classroom, choking and dying while the teachers banged her hard on the back and someone poked fingers down her throat!

The bigger boys were kicking an old football across the playground. I recognised Matthew Dalton in a blazer several sizes too small, worn shoes, and a torn shirt. The Daltons had been one of the poor families in the village. They had permanent colds, never wore the uniform, were often absent, smelt of urine and sat at the back of the class. As I recoiled instinctively, I remembered. As teenagers, Matthew and one of his many siblings had broken into a local farmer’s hay barn. The hay had caught alight and the fire spread rapidly. The fire brigade had been helpless, faced by an inferno. The two brothers had been burnt to death. Matthew was close to me as he turned to kick the football. The skin of his face was hideously scarred and his hands just fingerless stumps as he struggled to grasp the ball.

At the receiving end of the ball, I recognised Jimmy Gray. At school he’d always sat at the back, quiet and reserved. One of those children never chosen for teams, never shining academically, a nonentity, except for his bright flame-colored hair. Yet he achieved a type of fame or rather a notoriety! He had become a successful farm manager, running several large farms in the area. For some years he had had an affair with the wife of one of his own farm laborers. It had become so well known in the village that no one bothered to mention it. Even the gossip had tired of the topic! One gloomy November evening, the cuckolded husband had seized his two-barrelled rifle, marched up to the main farmhouse, and shot Gray twice through the head. Then he walked home, shot his wife in the stomach and himself in the mouth. His name was Michael Owen.

I watched Jimmy and Matthew kicking the ball backward and forwards. I wondered how they managed to target it or kick it at all.

A bell rang dully across the playground. A sudden silence descended on the now empty space. The long-threatened storm was about to break. As I walked to the old school door, lightning flashed across the darkening sky. For a moment, in the light, I saw my reflection in the glass panels. Empty sockets stared back at me from a face where thin white skin barely concealed the bones beneath. Thunder roared. The rain poured down.

- Big Fly - December 24, 2025

- A Green and Pleasant Land - August 4, 2025

- Spotlight On Writers – Sarah Das Gupta - February 22, 2025