AN UNUSUAL POWER: MAD-HOUSES: SANE OR INSANE?

written by: Stanley Wilkin

@catalhuyuk

‘Oh yes, all those Victorian husbands getting their wives put away,’ said a good friend, when I told her my plans for a book about sane people being declared mad in the nineteenth century. Many others subsequently came out with something similar. But I hadn’t got very far into my initial archival dig when the variety of victims of malicious asylum incarceration became apparent; it appeared that, anecdotally at least, this was slightly more likely to have been a problem for men than for women, certainly in the first sixty years of the century.

The above is not the thrust of this paper, but alludes to the uncertainty of psychiatric ideas and practices then and now. Many of the themes touched on here will be expanded on in later papers. Here, the nature of mad houses, of alienists or mad doctors, the consequences for their charges will be considered. What ideas of madness did alienists hold, and what treatments did they use? What social and intellectual conceits lay behind those ideas? This paper, in addition, will assert that theories of the origins of mental illness were constructed within the competitive economic environment of late 18th century and early 19th century public and private mad-houses, fashioning the idea of physician expertise in the field and of the necessity of incarceration as a method of recovery. This paper will show that concepts, then and now, of mental health are intrinsically bound up with mad-house economics, physician status, the judiciary, concepts of pauperism, and state enforcement. This paper will intimate that the mad-houses built both privately and by individual councils at the end of the 18th century and during the earlier part of the 19th century were symbolic of wealth, the power of the medical profession, and in line with the expanding prison system and state power. By this time, insanity was perceived as flawed or failed reason and understood mainly through concepts of delusion.

Competition and Capitalism:

According to Charlotte MacKenzie, institutions for the insane developed on an unprecedented scale in eighteenth-and nineteenth century Europe. Searching for a reason, Mackenzie notes Foucault’s idea of repudiation of the irrational in an age of reason, Karl Dormer’s notion of the desire for social control in newly industrialised societies, and Scull’s concept of mad-hospitals as the result of the demands of industrial-capitalist labour markets on family resources, combined with the self-promotion of the medical professions as experts on insanity. As most of mad-houses were privately owned, unlike on the continent, MacKenzie suggests that fitting them into ideologies of social control is difficult and that Roy Porter’s assertion that their expansion revolved upon predominantly commercial interests is the likeliest reason, if providing a superficial assessment of an extraordinary phenomenon. According to Porter, before the 18th century only a small proportion of the insane were locked away, but taken care of by charities, family or the parish. There were also probably far less of them, as the stresses of greater social complexity, brought on by capitalism, and the treatment and designs of doctors had not yet begun to create the multitude of sufferers now with us. The ‘great confinement’ begun by Louis XIV’s absolutism in the 17th century did not occur in Britain. Porter insists that instead England was subject to de-centralisation, with many decisions regarding the insane remained with local authorities. Certainly, the incarceration and treatment of the insane was in line with the increased use of prisons, where treatment and reform were the focus. As in mad-houses, inmates were subject to strict use of time and, later, of work activities designed to be therapeutic.

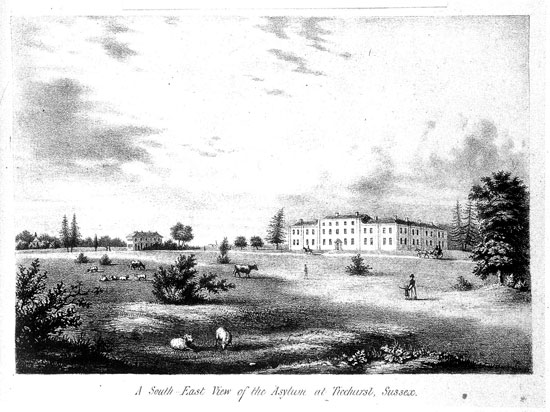

In tandem with the trade in corpses previously noted, the trade in lunacy proved profitable. It was however a mixed economy of care, as Wynn’s Act of 1808 encouraged county justices to establish lunatic asylums. The legislative and legal involvement and oversight of mad houses appeared in the earliest periods of lunatic-care development, in many aspects long preceding any scientifically considered treatment methods. By 1845 fifteen counties had provided asylums, but nevertheless remained a small total of the mad houses functioning in the UK. They were required to compete with more numerous and successful private mad houses. The impetus, as noted by MacKenzie, came from the wealthy-concerned with matters of social shame and financial expediency, the money connected to and controlled by unmanageable relatives. The public mad-houses were publicised as being places where the injustices of private mad-houses would not take place (Melling, Forsythe 1999: 34).

The problem of pauper lunatics was met by increased state involvement, with a focus upon subscription asylums based upon the success of York Retreat. Private mad-house proprietors hit back by offering free places for pauper lunatics, but county asylums still undercut their revenue by offering in turn places for the wealthy in their own facilities. As incarcerating County lunatics proved an expensive business, some local authorities preferred to have them roaming free within the parish, although this was considered to delay recovery. By now, the belief, contrary once again to actual practice, that physicians provided cures had gained ascendency. The equation had emerged of physician+judiciary+state-power+local authority power and responsibilities+location (Mad-House, with its attendant apparatus, personnel and treatments)=treatment+recovery.

In public mad-houses the wealthy, who paid, occupied the often magnificent central part of the building, (Melling/Forsythe: 1999:37), pauper patients were allocated to the wings, and charitable patients, sponsored by benevolent concerns or individuals, in-between. The wealthy were sometimes accompanied by servants and provided with additional rooms. Mad- houses usually had small patient numbers of say around 20 to 25. Treatments remained harsh for everyone.

Patient recruitment, then as now, was fundamental to the existence of mad-houses and alienists. The expansion of contract culture between mad-houses parishes and charities enlarged patient populations and increased the status of alienists, their treatments and proclamations, and the societal importance of mad-houses that began gradually to loom over the landscape. The idea of lunatics as separate from ordinary humanity, the division between the normal and abnormal, all focused upon the expertise of alienists/psychiatrists, was born, soon to flourish.

Secluded and secret (Porter: 1987: p 167), the owners of these establishments were absolute, perhaps prefacing the power of present-day psychiatrists. Later films and stories about tyrannical mad doctors have their genesis here. The criminally and intellectually dishonest practices of many owners went hand in hand with amazing confidence in their judgement, occasioning many instances of the false imprisonment of the sane at the insistence of their relatives, and the for owners and relatives mutual profit. Only from 1774 were legal safeguards put in place and mad houses were required to be licensed. Although Porter takes a sceptical view of some of the claims of false incarceration, treatments then were similar to methods of torture and abuse more common in previous centuries. In effect, the mad houses drove even the sane mad, or were capable of doing so.

As has been noted in The Cultural Construction of Madness, mad doctors or alienists were without systemic knowledge, but gained their expertise by direct experience-often prejudiced by prior assumptions of an individual’s insanity, relatives’ assertions, and commonly employed theories such as the Four Humours that encouraged treatments to be centred on the body, ignoring the mind, or rejecting its direct treatment on the basis that the mad no longer possessed one. Although the courts began to take an interest in the running of madhouses, neither they nor any other independent authority took any interest in the efficacy of diagnosis or treatments. Within the growing structure of the madhouses physicians began to create an effective power-base constructed upon unproven cures and poorly constructed theories. Both relatives of the insane and courts by the early 19th century began to implicitly believe in the diagnosis of physicians, so if they categorised someone as insane it became difficult to overturn that judgement.

The entrepreneurial nature of mad houses interests MacKenzie and those that these businesses abused. For her, as for Porter, this coincided with an age of economic success. Throughout this period, commercial transactions regarding confinement were conducted through cash, as with the transfer of corpses to medical teaching schools and hospitals.

Contrast:

There were, according to Anne Digby, changes towards the end of the 18th century whereby mad people were viewed not as beasts but as human beings requiring specialist ideas and thinking. While this is perhaps true the author wrongly attributes the former attitude to the distant past when it was more closely allied (The Cultural Construction of Madness) with the beginnings of physician interest in the insane, moody or abstracted. Before physicians became specialists of madness, the insane were often regarded with philosophical interest. Regarding the insane as brutes served to provide the rationale required to control them.

Notions of what constituted madness had nevertheless changed, and religious enthusiasm, for example, now indicated insanity. The use of imagination in either voluntary or involuntary capacity was a common idea of the time, attached to fantasy and the fantastical, and too much imagination, in association with excessive emotional expression, demonstrated a propensity towards insanity. These notions have continued into at least the recent present, underlying the incarceration of an excessive number of West Indian immigrants in the 1980s. Normality, expressed as balanced behaviour and feelings, conventionality and mediocrity, was on its way to offering an identifiable opposite to insanity- which has gathered under its umbrella all kinds of excessive traits, from joviality to genius. Digby (1985: p 3) also marks the 18th century connection of insanity and poverty, a consequence of the new cash society and the exploitation of the poor. Antagonism to the work ethic encouraged institutionilation by the authorities.

Although I dispute Digby’s belief that the mad were released from fetters of animal-like minds and behaviour by the 18th century Enlightenment, as in fact this belief remained until recently and was I believe the creation of mad-doctors, the philosophy of Locke, who insisted that mad people’s thinking was flawed rather than their feelings or souls being deranged may certainly have initiated mad-doctor’s changes in perspective. Violence towards the insane, based upon the need for control and retribution began to be challenged, although as Digby notes (page 11), changes in theory once again did not lead to changes in treatment.

Psychology (Digby: 1985: 9) emerged from this new attitude, although these papers will conclude that psychology rather than being valuable insight into human behaviour provides instead additional chains of normalisation and gentrification, representing a kind of elite wishful thinking.

Towards the end of the 18th century, mad-houses were mainly run by lay people and the general public was hostile to the involvement of physicians (Porter: 2004: 150). Benjamin Faulkner in 1790 wrote Observations on the General and Improper Treatment of Insanity, his ire directed at medical at physicians, claiming that they knew far less on the subject than experienced layman. The problem was then as now, that physicians required invasive, identified cures, theories that appeared correct rather than were, with everything crisply parcelled up in transferable bundles.

Two Mad-houses:

At this point, this paper will consider two mad-houses, one run by lay people and the other by alienists. Both represent different examples of ‘moral management’, a movement that began in the late-18th century. According to Porter (1987: p 19), this involved reclaiming the mad through the mad- ‘personal charisma, force of character and individually designed inventive psychological strategies, of which one noted example was a form of hypnotism.’

Patients first had to be subdued, then manipulated through their feelings-hopes, fears, sensitivity to pleasure and pain, necessity for self-esteem-to thereby return them to normality and engage once more with the social requirements of the time. According to Porter, the intention was to revive the dormant humanity of the insane. The leading lights of this movement were Chiurugi in Italy, Pinel in France and the Tukes, who developed moral therapy at the Retreat in York. The abiding insight, true or not, was that the lunatic’s association of ideas and feelings had caused delusions and thereby disturbed behaviour. The fault was judged to be (see above) intellectual. Lunatics were to be cured by rigorous programming and training.

Porter (1987: p 19) believes that the claims of alienists that their enlightened methods cured the insane encouraged increased institutionalisation. Alienists were on their way to becoming psychiatrists with all the kudos of real or imagined understanding and real or imagined cures. As a result, the number of confined lunatics increased rapidly from 5000 in 1800 to 100,000 in 1900. Was madness contagious or were psychiatrists already besotted with power? Did this escalation signify the growth of the profession, not the growth in mental illness?

The Retreat:

The Retreat, a mad-house created by Quakers, and run by William Tuke, later famous for establishing moral care, was opened in York in 1792. Quaker views of the mentally ill formed the treatment offered. Religion was emphasised based it seems on the peace it accorded many patients, religiously inclined when sane. They perceived the mad as retaining the ‘divine spark’ of all humans, possessing full humanity, in contrast to public asylum and many private madhouse supervisors who saw their charges as beasts. Patients were treated with respect, influenced through their capacity to understand, and the belief that understanding regenerated. The Retreat’s directors believed that patients were unfeeling and unthinking, distinguishing between reasonable and unreasonable behaviour towards them.

Although such a regime was not new in Europe, it stood out in marvellous contrast to other mad-houses in the UK. Humanitarian madhouses were established by Chiarugi in Italy and Pinel and Daquib in France. Pinel, a qualified doctor who advocated a scientific approach to madness, is most known today. Unlike the Tukes, he did not encourage a hands on approach to patients but one of greater detachment, whereby doctors watched and observed.

Apart from the prevalence of religious observance, attention has been placed on the real or imagined parental attitudes of the staff towards The Retreat’s patients and the belief that the insane were like children, having both the sweetness of children and the need for enforced discipline. Samuel Tukes (Digby: 1985: 58) commented on at least two occasions on staff parental roles towards patients and how patient’s filial attachments to their wardens. Surely Foucault is right here, believing that subsequent infantalisation (1967) was a method of control no matter how much Digby defends it.

As noted above, commonly treatments consisted of containment, deprivation and abuse. Individuals were treated with all the care of animals prior to culling. Wise considers at length the experiences of John Perceval, an aristocrat, while incarcerated in a mad-house.

Incarcerated and sane!

John Perceval:

Perceval, a son of Spencer Perceval the only British Prime Minister to be assassinated, lost his father at 9, and when he was 11 his mother re-married-to Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Henry Carr. A serious young man, he joined the army but found it conflicted with his strong religious views. He quit, entered Oxford University and in 1830 matriculated in 1830. While there he began to hear divine voices. Perceval heard about a group at Row, near Glasgow, who spoke in tongues, under the direction of the Holy Ghost. He travelled up to Scotland to find out more. Disturbed by the nature of religious experience, he left Scotland for Dublin where his confusions gained internal expression as voices gathered in his head. A tryst with a prostitute left him with syphilis, treated with mercury, and enormous guilt. As his behaviour deteriorated, he was tied to his bed by friends and a doctor called for. He believed that god/Jesus had descended to earth, his body now a battleground for good and evil.

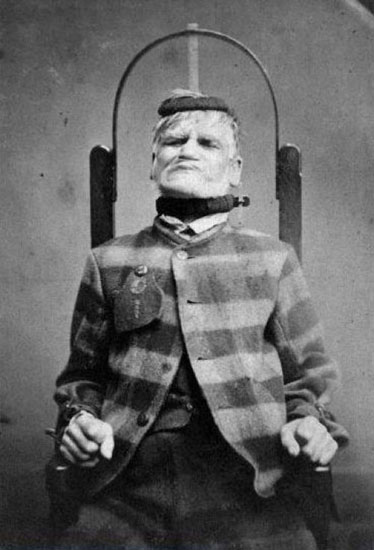

After further developments, Perceval found himself in Brislington House in Bristol, run by Edward Long Fox-called by wise ‘smugly ignorant’. Perceval was judged a violent lunatic and put in the part of Brislington Hall set aside for violent wealthy lunatics. The asylum was considered one of the better establishments of its sort. Although Brislington Hall advertised that no violence or restraints were used against lunatics, Perceval’s account demonstrates that such assertions were untrue. Perceval documented a place of torture, where patients were routinely strait-waist-coated and manacled, with leather straps across their bellies. Only occasionally were they unchained and allowed to walk around their rooms. During walks outside, permitted twice each day, patients, in despair, would attempt to self-harm. Each had an attendant who was liable to torment or beat the patient. At times, for one reason or another (Wise: p 36) they were bled, these procedures causing further harm. Essential to the overall consideration of psychiatry, then and now, the doctors attending the patients found it difficult to understand that the patients had access to the full range of emotional responses, and were subject to the usual or extreme sensitivity to a variety of issues. Of course, as now, they failed to completely appreciate that patients might be capable of cognition and intellectual capacity and development.

Brislington House, built in 1806, was perhaps the first purpose-built large private asylum in England. Patients were segregated by gender and social class. Partitions ensured that the various classes did not mingle. The violent and non-violent lunatics were also separated. The Fox family who owned and ran the establishment described it in glowing terms as a hospital for the curable and a comfortable retreat for the incurable. Visiting inspectors, local magistrates and local JPs who inspected asylums and awarded or removed licences, saw nothing wrong in the apparent abuses of Brislington House, and, of course, of many other asylums. Wise points out (page 48) that the Foxes were part of a the new, Quaker enlightened approach to lunatic care, one which forbade violence and cruelty against patients, but who ignored the habitual violence against their charges as they believed their staff over the testimonies of lunatics. The restraints and employment of cold baths/showers, also contrary to Quaker dictums, were explained away by the doctors as essential treatments. A recommendation by doctors, then as now, whether backed up by evidence or not, was deemed sufficient for most people. It usually is now. Complaints about doctors or treatment were usually referred back to the doctors who often ascribed it to the patient’s insanity. This was not a sign of alienist intellectual corruption but more to the belief that patients were incapable of high-level observation or decision making. Lunatics could not think!

Wise notes (page 48) that contrary to the 1828 Madhouse Act, the Foxes touted for patients and provided fast, uncomplicated certification. She demonstrates that their 1836 prospectus contains an invitation for customers, for that was what they were, to obtain blank lunacy certificates. The Foxes, like many mad doctors of the time and since, were in the service industry.

Although to any intelligent observer, the regimes at places such as Brislington House were damaging, causing behavioural and psychological deterioration, patient’s descending into animal-like behaviour-defecating without dignity and gobbling food as if beyond human civilisation-to the alienists who ran them this was not the case. Their care was at all times beneficial.

Although much of the above alludes to the experiences of John Perceval, the son of the only prime-minister to be assassinated, who subsequently claimed to have been wrongly incarcerated, who certainly recovered after a few years, these experiences were shared by many others. Attempts by Perceval to obtain release, according to Wise (2010), met with refusal by doctors, often earning large sums to continue his incarceration, and the dismissal of his perceptions and observations of treatment and the hospitals he lived in as products of delusion and imagination. Validity of perception belonged entirely to the doctors. Perceval, who may have simply been a victim of mercury poisoning, his incarceration lengthened by the psychological effects of treatment, later wrote at length about misunderstandings of the mad’s thinking processes, the denial that they had any, the need for each to be treated individually, and the mad’s surrendering of bodies and minds to doctors who were ‘permitted to work their mischief or test their misguided or unproven theories upon them.’ (Wise: 2010: p 63).

Later papers in ‘The Unusual Power’ will hopefully demonstrate that this has continued unabated. Patient’s minds and bodies remain under the control of doctors or other mental health staff, subject to their perceptions and treatments. John Perceval’s subsequent analysis of both his lunacy and treatment is full of perception, a font of interesting observations, but was ignored while the often ignorant meanderings of alienists were approved and repeated as knowledge for future alienists and psychiatrists.

The problem of developing psychiatrist knowledge, here and in many later decades, is the subjective nature of perception, of any attempts at observation, and the strict belief in the physician as the arbiter of the value of perception. Psychiatrist perception remains anecdotal.

Lunacy and toxic abuse:

The suggestion that mercury poisoning may have affected Perceval’s mental state can be viewed alongside evidence on the effects of paint materials of the time, lead for example and turpentine for thinners, especially in high temperatures. I.M. Monro speculates that this combination may have induced the madness of the artists Richard Dadd, J. R. Cozens, and Vincent Van Gogh.

While John Perceval’s case involved the use of incarceration after the patient had resumed normality that of Richard Paternoster was of a sane man suddenly certified into Kensington House Asylum by his father after a row about money. Richard had worked for a while for the East India Company in Madras, had become ill and returned to England. The Company arranged a pension for Richard of £150 per annum, paid to his father who was then required to pass it on to his son. He did not, and Richard was reduced to penury. He wrote his father a number of threatening letters that resulted in his incarceration.

Attempts to prove him mad failed, but the Magistrate overseeing his case referenced only the two lunacy certificates and order, signed by Richard’s father, and not the evidence before him. Paternoster was taken from court by an asylum owner and incarcerated forthwith. The Press of the day responded to the case and Richard was soon released. Throughout his confinement, Richard made note of the killing of a patient by an attendant and asked questions of his fellow male inmates, finding only a few to be insane and concluding that most were incarcerated by relatives for reasons of money.

Such cases appear to been made possible by the 1744 Vagrancy Act which allowed vagrants assumed to be mad and thereby dangerous to be incarcerated with the consent of two justices of the peace (Byrum, page 40). No medical certificate was required. Also, as Bynum states (1981: page 41) anyone could open and run a mad-house. The 1774 act that licensed mad-houses failed to mention that proprietors should have qualifications. Would it have mattered, given the immense brutality of the mad-doctors?

Once Paternoster was free, both Perceval and a William Bailey, an inventor and businessman, who losing money in speculation and had been subsequently incarcerated by his wife in Hoxton House Asylum. With the support of Paternoster and Perceval Bailey went to court to redress the injustice, but his wife immediately applied for him to be once more incarcerated. Moved from asylum to asylum while paternoster and Perceval took the matter to The Metropolitan Commissioners but although eventually released effectively his life was ruined.

These cases reflect on the power of doctors, the belief invested in them, and responses then and now to insanity. Asylums were places to jettison unwanted relatives, where doctors would collude as a consequence of their knowledge of mental health, stemming from physician’s authority and imagination rather than analysis of all possible perceptions. Professions of others’ insanity tends to be anecdotal and dependent on power constructions, social prejudices and subjective perceptions of normality and the nature of thinking. A lunatic can be someone we dislike, someone who dislikes us, or, as commonly, someone who is a threat to others’ assumed well-being. During the early Victorian period, asylum owners were involved in trade, offering their status and power for economic transactions, their treatments tending only to increase mental disaffection, not cure it. They traded in lunatics, real or imagined, as many doctors at the time still traded in corpses.

Certainly a pivotal event in psychiatry’s development was Francis Wills, and his sons’, treatment of George 111 involving his body being encased within a machine, without possibility of motion, frequently beaten and starved, and exposed to verbal intimidation. In addition the poor king was subjected to blisters, bleeding, digitalis, tartar emetic, and other kinds of diabolic treatment. As Bynum informs, not everyone agreed that the king was mad, but as the mad-doctors were treating him that was the treatment he received. Wills considered his therapy appropriate, although it appears akin to exorcism. Wills, upon little foundation, believed that there existed two kinds of souls, one sensitive and the other rational, the latter possessed only by human beings (Bynum: 39). Bynum concludes that Wills’ take on madness does not make sense as he believed that while a specific characteristic, the rational mind of humans was dependent upon the brain, thereby making pointless his belief in the soul-like qualities of intellectual faculties, and also Bynum queries as to why he should believe that medical therapy, especially of the kind practised by mad-doctors, could affect a problem with the intellectual faculties. Bynum points out that this makes sense only if his belief in humours is considered, which insisted that the physician should treat the body or parts of the body to treat problems of all kinds. What also must be considered is the mad-doctors notion that lunatics are insensate, and unable to think or feel appropriately. Assualt upon the person might then be understood as an attempt to arouse the higher faculties.

Bynum sees this therapy, still practised today in some form or another, as moral therapy, in the sense that it was the mind being appealed to. But the Science (sic) of Humours dictated that moods were associated with the body, or a part of the body. Invasive treatments concentrated on the body, and, through that conduit, the mind.

Medical treatments of the day:

The treatments devised for lunatics described above were not unusual. The American alienist Benjamin Rush described his methods to Dr. Willis who attended George 111 as:

‘…..frequent but moderate bleedings, purges, low diet, salivation and afterwards the cold bath.’

Designed it seems to counterbalance observed psychical traits associated, usually wrongly, with apparent mental conditions. Each of these treatments altered the complexion of the patient’s skin or affected their urine or foetal matter.

Constraints, as described above, were employed to prevent the patient from harming themselves or others, but owe something to the view of lunatics as related to or referencing gargoyles and other sinister creatures, as identified in ‘The Cultural Construction of Madness’. The beatings, sensory deprivation and the elimination of intellectual pursuits, resembled the camps of the holocaust where inmates were reduced to survival only. As in this instance, the Jews were the Other, their suffering ignored or denied, lunatics were considered unable to feel or think. The banning of writing in general, noted by Perceval, reflects on the physician’s fear of alternative, possibly superior, perceptions and the aligning of creativity and madness. In many instances, creativity then and now was viewed as something to suppress.

Left out of many histories of the treatment of the insane are the physician’s and carers’ anxieties as if the only alteration or misalignment of feeling and behaviour lies with the lunatic/supposed lunatic. In fact, mad houses were also a protection for the Alienist, shielding examination of a need to torture and dehumanise, and any examination of their own perceptions and behaviour.

Distinguishing lunacy:

Perceval, Paternoster and a Captain Saumarez (Wise: 2012:71) amongst others, gathered together to challenge mad-house incarcerations, campaigning for a lunacy Select Committee to oversee incarceration, thereby protecting individual rights. Although they seem to have achieved little, a Commission of 1844 to the Lord Chancellor replicated many of the groups concerns. Both unfortunately, and interestingly, the report included a further definition of lunacy, one that would have been understood and appreciated by the burghers of Norwich and Bristol in the 17th century, referring to the morally insane, exhibiting social and moral maladjustment such as habitual drunkenness. The Commission’s concern was not the lack of justification for incarceration, as now lunacy included also the anti-social, but when a person was cured and could be freed.

The small pressure group were also faced, as many reformers now are, with the duplicitous and multiple nature of lunacy, in that some appear ordinary, leading normal lives until their delusional thoughts eventually overwhelm them (Wise: 2010: 76-77). The fear of violent lunatics usually beats public concern over bad treatment of the mad in mad-houses. Famously, lunatics often claim not to be mad, and equally will claim to be objects of a conspiracy. Nevertheless, upon hearing that Lord Shaftesbury’s plan to overhaul lunacy legislation, Perceval, Paternoster, et al, form themselves into the Alleged Lunatics’ Friend Society.

In 1845 lunacy legislation, allowing for each county to provide an asylum for their pauper lunatics, was given Royal Assent as well as the Act for the regulation of the Care and Treatment of Lunatics, that insisted that clear reasons must be provided by a doctor for incarceration and the time limit for mounting legal action claiming fasle imprisonment was extended from 6 to 12 months. Nevertheless, the patient could not legally know who had originated committal, what was the proof of insanity, or attend hearings where his/her lunacy was discussed (Wise: 2010: 82). Matters in including and making note of the ‘insane’ persons voice is still a matter of concern. Perhaps more so now, the medical profession’s voice dominates, with the continued belief that patient’s cannot intellectually access insight into their own minds and behaviour.

Wise (2010) documents a number of further cases of both women and men falsely incarcerated. One important case detailed by Wise was that of German Professor Edward Peithman who innocently had wandered into Buckingham Palace to discuss educational reforms with Prince Albert, a common occurrence in Saxony where he and Prince Albert were from. He apparently expected to receive an appointment. As in The Cultural Construction of Madness, in Britain any breaking of spatial barriers with royalty invariably ended in committal. The police were subsequently called to the palace and Peithman was escorted to the Home Secretary. Upon the Home Secretary’s insistence, Peithman was incarcerated in nearby Bethlam Royal as a lunatic. Abetting the case against Peithman, his lack of money identified him as a pauper and his insistent attempts to contact the Home Secretary in order to get his commitment overturned further convinced those in power that he was a dangerous madman.

Meeting Peithman while visiting another patient in Bethlam, in 1850 Perceval decided to take up his case. Perceval’s research suggested that Peithman’s incarceration had been the result of his refusal to lie on behalf of Lord Cloncurry, whose sons he’d been teaching, when one of his sons made a maid pregnant. The maid was threatening exposure. Peithman owed the position to the very Home Secretary who had him incarcerated. Although Perceval obtained his release, the old academic was eventually forced to return to Germany.

Wise (2010) documents also the incarceration on the insistence of her mother of a woman who had joined a religious cult. Although already in her 40s, the woman, Louisa had long been controlled by her mother. Two doctors signed the certificate after talking with her, claiming that her religious beliefs, with which the doctor did not agree, demonstrated her insanity. Another member of the cult was described by doctors who had not actually met, but received versions of him by his relatives, as suffering from monomania. Perceval effectively demonstrated that her religious beliefs all fitted well into scripture, suggesting that the doctor’s ignorance of such matters affected their judgement. As Wise shows (pages 108-109) Louisa’s continued incarceration was based upon the idea of monomania, in which no sound mind would now hold true. It was in fact a difference of opinion, but interpretation lay with doctors.

A court that looked into Louisa’s confinement correctly asserted that Louisa was entitled to her religious views without thereby being judged insane, and that the doctors had acted upon the mother’s assertions alone.

Modern World:

All the above miscarriages fit with many instances I have witnessed far more recently, suggesting in-built, enduring cognitive flaws within psychiatry. These cases can be placed under several separate headings:

1) Parent manipulation, and desire to retain control over supposedly rebellious offspring.

2) The whims of the powerful.

3) Political contingency

4) The uncertainty of mad-doctors/psychiatrists expertise and theories

5) The unwillingness of psychiatrists to explore alternative viewpoints.

6) The widespread reliance by doctors on anecdotal evidence.

7) The power of doctors

In the 1960s and 70s very little had changed. As I will demonstrate, many young people were freely diagnosed with mental illness at the insistence of controlling parents, in one certain case the parents’ were paedophiles. The evidence for this instability came largely from the parents. In another case, a distraught young man who had endured a difficult relationship with his father confessed to a GP that he wanted to kill his father. The young man was angry. He was confined to a hospital for many years.

In addition, alienists’ control of writing, and fear of its agency, have continued up to the present day. Further papers will provide evidence of psychiatrists’ association of writing, particularly creative writing, with lunacy. The suppression of all forms of creativity, unless that creativity is controlled through, for example, occupational therapy, also survived up until the recent present.

Locke:

The philosopher’s construction of rationality as a separate and opposed form of perceptual-based irrationality, whereby cures were the result of misalignment, was based upon bourgeois constructs of property possession and retainment; community ideals at a time of growing capitalism. Therefore, he viewed reality as concrete and perception allied to practical/concrete acts and events. A sane man engages with the external world, an insane man with, at best, an internal one. From such a position we arrive at notions that normality involves creating money, acquiring property or holding down a job, and insanity is opposed to such things. Although this position was adjusted with the identification of temporary madness (The Cultural Construction of Madness), it has nevertheless prevailed and is the ghost behind concepts of ADHD for example.

Bethlam/Bedlam

The author of an early book on New Bethlam, built in 1812 on the site of a public house, asserts that it has been realised that ‘force and terror’ do not, after all, provide a cure, which was the established purpose of Bethlam since its earliest days. Bethlam was then part of the Bridewell estates and supported by a number of London institutions, such as the bank of England, East India Company and private individuals. The accepted treatments were mildness, care, strictness, usually light if repetitive manual work and incarceration,

The new asylum was capable of housing 200 patients. The building’s wings contained the patients, each wing containing four galleries, with twenty three bedrooms, and an infirmary. Of the four galleries, the basement was employed for ‘noisy and dangerous’ patients, the ground level for new admissions and curables, the third level for curables too, and the fourth level for incurables/criminally insane. The centre of Bethlam was for resident officers, the apothecary’s shop and servants’ hall.

The book itself, according to P. Allderidge, demonstrates callousness towards the patients, with each being held up to ridicule. Others, such as Paul Chambers, regard it more positively as it details reforms such as regular and rigorous care routines. No more were patients left half-naked, chained to walls in dank straw. The book displays obsequious descriptions of the hospital and its managers. Although ridiculing attitudes were probably prevalent amongst the general staff, Allderidge believes the author was a former attendant named James Smyth, who had left Bethlam shortly before the book was published.

The work describes many home-comforts, such as clean linen, except for the criminally insane or incurables. The author describes the illnesses of 140 patients, often in lurid detail, a number of which had already left the hospital and returned home. Many of the patients were ex-servicemen, serving in the navy or army, who had seen action and were subject to bouts of violence or delusions. Many were possibly suffering from trauma or brain damage, with the asylum serving as a prison.

There is no real diagnosis or interpretation within the book, written mainly it seems for profit, and nearly everything recounted by the patients is derided as clear evidence of their lunacy. Some of the patients’ statements may, for all we know, have been meant playfully, as attempts to ridicule staff, or methods of communicating difficult feelings. All remarks by patients are nevertheless considered the blatherings of lunacy (disordered imagination/delusion). This was probably the attitude of the alienists, perceiving lunacy as affecting the whole person, causing a Lockean disruption of reality, and completely separate from the norm.

Allderidge is particularly interested in evidence for Schizophrenia, which many commentators apparently view as a modern disease. He finds possible evidence only in one case, that of William Adams who suddenly became mad at 27. Allderidge perhaps correctly attributes the lack of clear evidence to writers of early case-notes, but does not nevertheless engage with the possibility that hearing voices did not occur or rarely occurred at this time. Nor is mania in clear evidence, but most patients are presented as delusional, the severity of their delusions measured by the degree of violence patients’ employed. Many of the patients’ delusions were connected to power, omnipotence. Was this perhaps a reflection of the power of alienists, returned in a focus fit of communication? In situations where reality is modified by power, reality itself becomes suspect.

Problems of psychiatric perception and/or attribution will be dealt with in further papers- as will concepts of ‘cure’.

- A Strange Place - December 5, 2025

- The Puppet Dance - August 15, 2025

- Until I Stopped - April 23, 2025