THE CULTURAL CONSTRUCTION OF MADNESS II

written by: Stanley Wilkin

@catalhuyuk

Representations of madness, from medieval period to Early Modern period.

IMAGES:

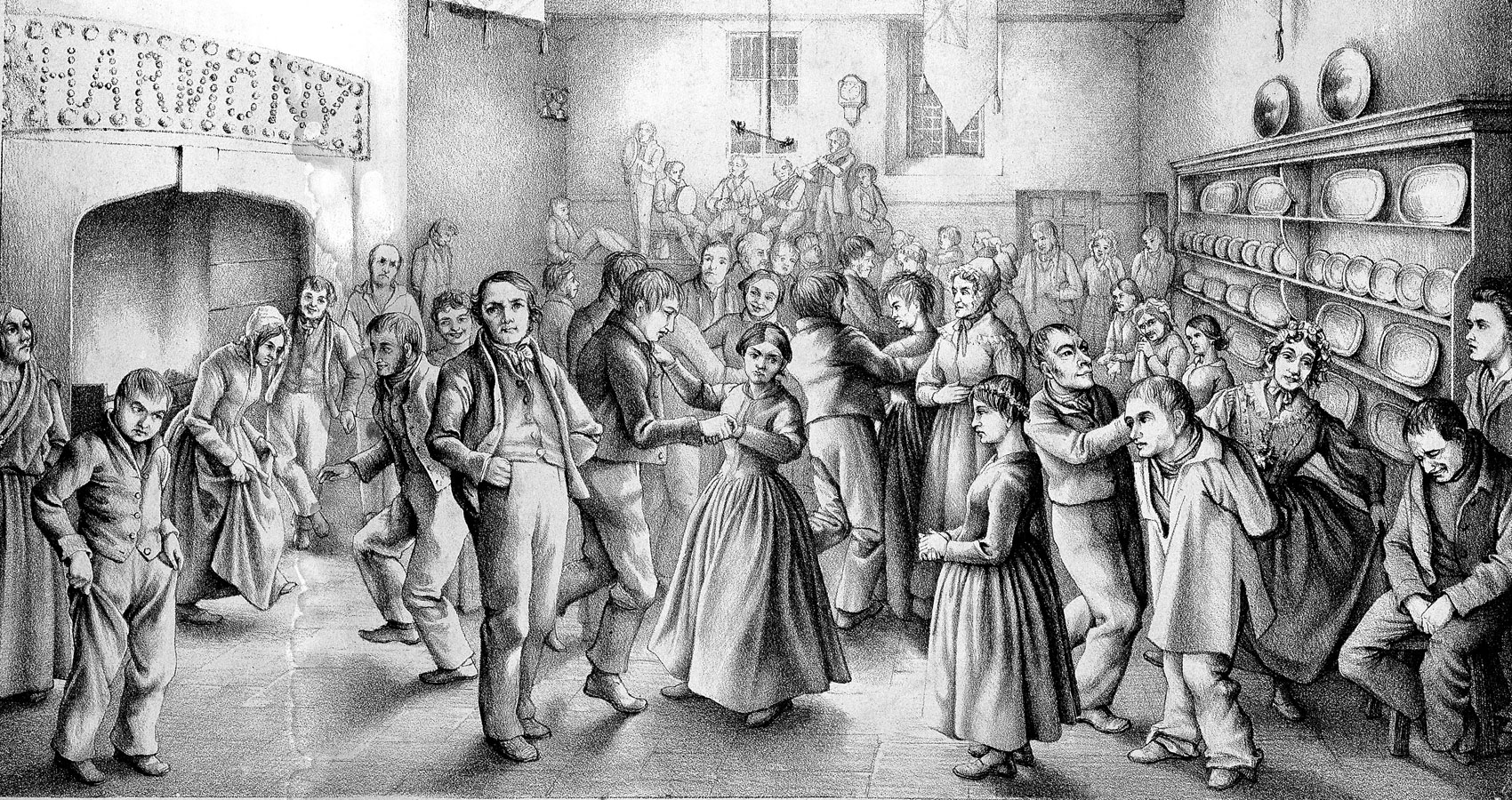

Dancing was employed as a therapy for lunatics, based on the effects of extreme physical activity and motion. Henricus Hondius engraving (1642) based on Breughel drawing of the pilgrimage to Molenbeek.

Dancing was employed as a therapy for lunatics, based on the effects of extreme physical activity and motion. Henricus Hondius engraving (1642) based on Breughel drawing of the pilgrimage to Molenbeek.

Images, engravings and paintings, contain perspectives and reflect a period’s thinking. Gilman (1982) has provided extensive examination of how the mad were regarded from medieval times, referencing physiology, symbolism, posture and gesture. Mental illness is viewed, within these pages, as evidenced by darkness of skin colour and furrows on forehead aligned to astrological signs and humours. Legs crossed in a seated position, elbows on legs, and hands under chin or holding head indicates reflection and grief induced madness of the melancholic. Often the mad were shown in contorted positions, clear evidence of their internal struggles. In many paintings identifying mental illness the principal figure hides their hands, indicating ineffectuality.

Gilman notes that, certainly in early medieval times, madness is shown as the result of possession with Christ or a Saint representing the divine driving out the consequences of earthly corruption. While often cures for mania are shown as within the realm of religion, those for the melancholic are shown as belonging to the physician, of the physical intervention, blood-letting, cauterisation, common at the time for dealing with an excess of black bile.

As will be seen, images of confinement appear mainly from the 16th century onwards and prior to this the mad are related to activity in the countryside, often prancing or dancing. The latter, combined with music, was perceived of as a cure for mania, foolishness and melancholia. Gilman also references the cutting out of the stone of folly, the removal of real or imagined protuberances in the forehead. Paracelsus saw madness as related to the abdominal region, and others in the backside. It clearly possessed physical traits that could be subjected to surgery. Early modern society sought for physical evidence of madness: goitres or ‘black bile, black demons, black stones, black rats.’ Gilman rightly points out the attempt to make concrete the internal drives of mental confusion.

The fool, the mad, appear to have been important Images of the mad until the 17th century tended to show them as existing amongst wild places, often seen as reflecting or connected to nature (Gilman, 1982: 8). In essence, mad people are displayed as freer than the sane until their space, water, nature, the world outside of human environments, is subjected to restrictions, incarcerated on ships, or put into cages and shackles. In Lucas Cranach the Elder’s 1532 painting Melancholy, the melancholic sits in a corner carving a stick into a bifurcated staff, an image of mental illness, half in and half out of the natural word of trees and mountains. To the left of the picture are the various humours on zodiacal beasts representing madness. The melancholic is nonetheless contained and although connected to wildness is likewise connected to order (Gilman, 1982: 8) indicating perceptual change. Gilman demonstrates an association between mad people and witches, who employ their staffs to fly, thereby further escaping from the restrictive human environment. A further indication of the freedom of mad people is that they were often portrayed as naked, for example Cibber’s statues above Bethlam, creating an association with barbarians in the classical world, who too were of the wild and rejected order.

Like a grotesque in appearance, a madman is represented as physically powerful, even demonic, and therefore requiring constraint. This is less a man than a demon. Compare with the expressions and muscularity of images below. Charles Bell’s ‘Madness’, Essays on Anatomy of Expression in Painting. (London: Longman, et al.,1806). The rage of the madman is apparently based on internally generated fear. The demonic appearance of the grotesques below can possibly be traced back to images of Ishtar, Mesopotamian goddess of sex and war, and other early Mesopotamian deities. It is certainly an image of destructive power.

Like a grotesque in appearance, a madman is represented as physically powerful, even demonic, and therefore requiring constraint. This is less a man than a demon. Compare with the expressions and muscularity of images below. Charles Bell’s ‘Madness’, Essays on Anatomy of Expression in Painting. (London: Longman, et al.,1806). The rage of the madman is apparently based on internally generated fear. The demonic appearance of the grotesques below can possibly be traced back to images of Ishtar, Mesopotamian goddess of sex and war, and other early Mesopotamian deities. It is certainly an image of destructive power.

HAMLET: PRESENTATIONS OF INSANITY.

According to Gregory J. Reid, tragedy and madness were always closely allied in theatre, although this does not acknowledge the role of the fool, foolish or comedic types with addled wits that appear in comedies. Reid cites Hallman who conceives tragedy as involving the individual’s inability to achieve identity. But, surely, it is extreme external and internal events that connect tragedy and madness, the latter being an expression of the former. Reid’s own definition provides points of interest worthy of discussion (2002, page 39): ‘madness in tragedy is a discourse resulting from the negation of the individual’s sense of reality.’

Jacobean Revenge Drama involved many instances of madness, seen in Kyd’s Elizabethan exercise in revenge, The Spanish Tragedy, in which Hieronimo, the main character, and his wife, Isabella, descend into madness as a result of their son’s murder. Often, in these dramas madness is linked to extremes of behaviour involving violence, many, if not most, involve women achieving autonomy, or asserting themselves in a world in which their feminine identity has been subverted. Babb (1951) states that Elizabethan drama (surely, Jacobean more so) ‘is notable for its psychopathic characters’ (whatever that means) and the number of physicians who appear on stage to provide treatment. The reasons are usually connected to remorse and love, i.e. the passions, and cured by subterfuge or simulation of passion by the physician. While essays on grief, of one kind or another, they provide a discourse on sense and reason, whereby emotions outweigh and prevent the development and employment of reason unless provoked to do so by an external agent.

Shakespeare was probably thinking of melancholia when considering the real or feigned madness of Hamlet. This fashionable intellectual condition suited wealthy members of the Tudor and Jacobean elite. Although Carol Thomas Neely accepts that early modern concepts of madness drew on Galen and Aristotle and the notion of humoral constructs of illness, she nevertheless denies that the subject was viewed as a unified discourse but involved heterogeneity. She perceives drama as developing a language of madness indicating an increased interest in the matter, involving (Neely, 2004: pages 2 and 3) the secularisation and medicalization of madness, separating conditions from theology and ideas of possession. Ian Hacking named this process ‘the secularisation of the soul.’ Hamlet can, with considerable justification, be called a ‘fully fledged psychological drama which focuses at unprecedented length on the protagonist’s tortured mental condition.’

Clearly, melancholy formed a substantial part of early perception of mental illness, distinguished from madness and variable in its effects It describes conditions of dementia and of relative normality, of morose temperament and of someone subject to hallucinations. During the Early Modern period it was associated with genius, particularly on the continent, and thereby attractive to the emerging intellectual class. Such was the faddish nature of the condition that epidemics of the illness broke out in England at the end of the 16th century, constituting a social type, malcontents. Many men of letters, for example, John Donne, Chapman, Greene and Nash amongst others, assumed or engaged with melancholy, thereby advertising their talents and their intellectual scepticism. Shakespeare, an actor, business man, and family man, appears to have been free of such mannerisms.

The illness, if that is what it was, is surveyed by Robert Burton in The Anatomy of Melancholy published in 1621. A very popular work in its day, it has its roots in the Renaissance, during which it was one of the accepted mental diseases along with madness, frenzy, hydrophobia and epilepsy. Burton was apparently motivated by his own intense melancholy. The disease involved fear and sorrow without external cause, varying in intensity from ‘relative normality to a dementia characterised by intense agony of mind and fearful hallucinations’ (Babb, 1959). A huge book, it dissects melancholy through the simple strategy of dealing with the condition in several sections, beginning with the consequences of original sin. Grief and guilt over human banishment from Eden and separation from god are the real reasons for human madness. This is divided into three sections, or partitions: after consideration of its causes, cures are considered, and the third part dwells on love and religious melancholy. Once this is concluded, there are digressions on anatomy, air/atmosphere, and the nature of supernatural beings. In the third book he love-melancholy, the mopping of the young lover, and religious melancholy. In lengthy passages he considers how the passions can cause melancholy, devils and learning can equally cause the condition. Although rarely touching on the severe depression identified by modern physicians, it nevertheless conjures up the present through its popularity amongst people in general, a metaphor for every stage and event in life. Like many of his contemporaries, Burton saw human beings as the most noble of God’s creatures, that perfection whittled away by social injustice and social ills, and their own importunes behaviour. It is the act of living that largely causes the condition, and human kind’s unreasonable behaviour in acting cruelly and selfishly rather than obey God and behave rightly and righteously. Unable to achieve the perfection before the fall, human beings fall into melancholy.

Burton presents melancholy within the paradigm of medical perspective, seeing excessive or original thought and behaviour as causing or symbolic of human aberration, observed in his use of Hippocrates as the central judge of others’ thoughts and behaviour, and (page 33) employs Bedlamite insanity to weigh the credibility of both language and understanding. Melancholy has assumed the preponderant, mischievous effects of the devil, placing unhappiness and madness as central to human experience. Madness and badness, of individuals and society, are exhaustively connected. The devil and his minions no longer play such a causative part in human lives, there are no longer the ancient intermediaries between humankind and god. Melancholy can only (pages 70-71) be treated when the ideal society evolves, Christian and centralised.

In essence, Burton describes the effects of social change: of the effects of social mobility, anxieties explicit in individualism, and the fragmentation of belief, greater self-consciousness and concentration on human rather than godly nature. He separated, or began the separation, of experience from human nature, implicit in modern psychology. Life, death become absorbed in metaphors of pathology.

Although Shakespeare employed several ways of analysing behaviour, witchcraft (Macbeth), in Hamlet he presented an individual’s inner world, albeit through the metaphor of feigned and actual melancholia, communicating and dramatizing his own thoughts. In Chaucer behaviour is presented without interior motivation, expressing a concrete world cheerfully mocked but not deliberated over, while Hamlet provides the language and world of thought. He possesses interiority, and changes himself through his relationship to himself. A new human being is here presented, conferring with himself not with god or the devil, fundamentally concerned with understanding himself and constructing a relationship with others’ motivations. It is from that relationship with ourselves that all the abstractions of mental illness, its reflected suffering, comes from in the present world, resituated by psychiatry into an external phenomenon. Bloom (1998: page 741) examines the possibility that according to a Dutch psychiatrist, J. H. Van der Berg, the birth date of the inner self can be traced further back then Hamlet, to 1520 when Luther, in a discourse on Christian Freedom, distinguishes the inner human from the physical one. From the 17th century, although of course this is a hopeless generalisation, the inner self became both fundamental and functioning, exampled by Hamlet: ‘his world is the growing inner self, which he sometimes attempts to reject, but which nevertheless he celebrates almost continuously, though implicitly’ (Bloom, 1998: page 405.) Hamlet’s mind is not simply self-evident, made public to the theatre audience, offered to their gaze, and exposed to examination by the audience, but it is fetishized, the origin of many and various responses: time, hero-worship, charisma, youth (although Hamlet is not that young), lust and the gamut of relationships. From these clear beginnings, the mind has now become the focus of physician and lay person alike.

Neely (2004) demonstrates that the two earliest English plays dealt with madness, connecting the behaviour of important characters to their responses to loss, grief and rage, referencing the ancient Roman dramatists but not their earlier Greek counterparts in Athens who employed extreme emotions and principles, usually within outsiders such as women, as drivers for their plays. In Gammer Gurton’s Needle Diccon the main character is portrayed, according to Neely, as a trickster figure who feigns madness and to others as a wise fool bringing difficult truths about character and behaviour to light. In essence, he is an outsider, disruptive, of no social role connected to the vagrants and nomadic thieves discussed in early parts of An Unusual Power. Causing trouble amongst the leading figures of a village he then ascribes madness to each when they respond to his lies. Neely (2004: page 31) states that Diccon’s ‘bedlam’ status is a metonymy for madness that is not outside but inside the normative social categories of ‘gender, class, sexuality, locale, and profession.’ Social order representing perhaps one illusion, if a commonly accepted one, and madness another, that of chaos, the outsider and truthfulness.

In Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy, the main character, Hieronimo, and later Isabella, his wife, have become mad, or distracted, by their son’s murder. As in ancient Greek tragedy, clear reasons are given for the subsequent excessive behaviour and emotion of a principal protagonists. Although in the original form of the play, Kyd alluded to Hieronimo’s madness only once, later additions, perhaps by Ben Johnson, make it more central to the character’s actions. His madness is represented as a failure to grief properly and accept his son’s death. While Isabella’s grief leads to her suicide, Hieronimo’s leads finally to recovery and action against his son’s murderers. Neely sees the play as developing understanding or identification of madness by presenting it as ‘inward, secular, self- generated’ (Neely2004:39). Madness is a matter of individual responses to recognised situations and conditions not due to outside supernatural intrusion into the world of the living. It is connected to a protagonist’s character, their ability to deal with difficult truths and reality. The madness highlighted in both these early dramas illumines real motives behind the cloaking of behaviour and motive that represents the social state, particularly of the growing ranks of the bourgeoisie towards whom Jonson’s satirical attacks were often directed. In addition, the mad characters take a subversive and heroic stance against the corrupt cultures around them.

The theatre’s exploration of madness may not have been the norm in a society that was still intensely religious, with a profound belief in good and bad. The views of playwright’s may have been a response to social change, urbanisation, introduction of waged employment, greater interest in social order, and the growing belief that human beings were rational and controlled their own fate. Neely details (pages 47-48) the professional history of Richard Napier, still practising in 1634, minister, doctor and astrologer, many of whose patients believed their mental problems were caused by witchcraft. Napier administered combination remedies, reflecting medical, religious, and astrological practice. While Timothy Bright in his Treatise of Melancholy (1586) tended more towards secular explanations based upon natural causes. Edward Jorden’s A briefe discourse of a Disease Called the Suffocation of the Mother (1603), distinguishes between natural causes of distraction through uterine disease and ideas of witchcraft as a factor. Neely (48) suggests that all three were intent on legitimising the expertise of licensed physicians. Reporting of possession declined throughout the 17th century in England, as the new physician-based explanation very slowly became established and over time mental illness became more the province of the physician and not of the church.

Neely identifies a new portrayal of madness through theatrical discourse, utilising a ‘peculiar language’ (page 50) rather than through physiological symptoms, stereotyped behaviour and iconographic conventions. A language that is both coherent and incoherent, playful in aspect and rarely to the point. The speaker wanders around through various aspects of commonly shared culture, employing prose and poetry and whimsicality laden with meaning. In this language of alienation, intellectual control of meaning is never entirely lost. In Shakespeare, according to Neely, this tool allows for the presentation of melancholy, feigned madness, female distraction in Hamlet, witchcraft in MacBeth, demonic possession, dementia and guilt-caused despair in King Lear.

In Hamlet the mad speech serves not only to display distraction, but to distract others from motivations and reasons for the feigned or real distraction, putting enemies off the scent. It, like the examples above, throws light on other’s behaviour while avoiding or delaying confrontation. It is often employed to implicate, an internal dramatic devise like the play within a play, allowing a character to indicate other’s guilt without assuming complete responsibility. In this it is connected to Alan Mercer’s more recent TV plays on theatrically presented schizophrenia: Morgan: A Suitable Case For Treatment, and on theories of the message-laden nature of mental illness put forward by R. D. Laing.

As Lidz (1976), who in other ways takes the psychiatrist’s view of madness as anything and everything habitually and emotionally excessive is therefore insane, notes, observers of Hamlet’s behaviour do not blame the usual reasons of the time for his insanity, such as witchcraft, possession, sin or humours, but to real-life events. Ophelia’s madness exacts the same response. That Hamlet’s madness is a plot devise, a strategy of the main character, is on the one hand indisputable but on the other appears caught up in genuine indecision and gathering sadness. He thereby feigns disturbance but at the same time is deeply disturbed by his mother’s sexual iniquities. His madness concerns not his own sin it seems, but that of others.

This book has considered how the flow of populations between countryside and town/city was negotiated and the need to continue to impose order on migrating groups will here also look at changes in 16th and 17th century social order and . The constriction of the mad person’s world, their restriction into ever smaller confines, was part of this urban evolution. Like barbarians at the time of the Roman Empire, as seen through chroniclers of the time, the mad represented the threat of wildness, freedom, the unknown and anarchy as well as being a cause for amusement. In literature, madness gradually loses its foreground presence, emerging, and why will be considered later, in weakness of mind in Dickens, and in incarceration of mad relatives in Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre.

WITCHCRAFT AND ITS CONNECTION TO MADNESS:

Through symbolic representation, witches occupied a number of references employed for the insane, such as otherness, appearance, and differences in thought and behaviour from society in general. Their association with wild mountainous terrain connected them to wildness and danger.

In 1484, prior to the period under consideration, Malleus Maleficarum, written by Fr. Henry Kramer and Fr. James Sprenger, was published in Latin. This dealt with the discovery and apprehension of witches and sorcerers and provided a text-book on the subject for inquisitors. Aside, but connected to madness metaphors, witches were regarded as revolutionaries who attached accepted social order, undermining all religious institutions. Witches and sorcerers were regarded as elements of organised rebellion against Lords, Church and the natural order of things. The tome gave authority to the idea that mental illness was the result of demon-possession. It also connects women directly with evil as a consequence of their insatiable lust (Bromberg, 1975. Page 43).

As evidence of witchcraft grew exponentially, learned doctors published diagnostic treatises, allowing for conditions to be swiftly identified. The symptoms were presented as: resistance to medical diagnosis, loss of appetite, sexual impotency, languor and sudden mania (Bromberg, 1975: 46). A further sign was the evidence of skin blemishes, indicating points of contact with Satan. These beliefs were held by medical practitioners until 1700 and beyond. Sir Thomas Browne was an advocate of the effects of the Devil on ‘humours.’ Inquisitors, tenderly and altruistically tortured their fellow man/woman in order to drive out intrusive devils and thereby save people’s bodies and souls. Even, of course, if it killed them in the process! For many centuries after the publication of Malleus Maleficarum witchcraft and the devil’s work was seen as an established scientific fact often taught alongside the science of physical causation. In 1584, Reginald Scot published Discoverie of Witchcraft claiming that what appeared as the consequences of witchcraft often had natural courses.

Although according to Bromberg (1975) increased literacy caused cracks in the mass illusion of witchcraft and the devil’s unruly intervention, events in Northern America and Europe testify that it went on with considerable energy throughout the 17th century. William Drage, both a practitioner and teacher of medicine, wrote in 1665 Daimonomageia: A small treatise of sicknessers and diseases from witchcraft, and supernatural causes…., which detailed a woman’s possession by two devils. She was sent to a Dr Woodhouse who ‘prepared stinking Suffumigrations, over which she held her head.’ The disgusting smell of the concoction reciprocating that of the devils, thereby like for like occasioning a cure. The woman then began making animal noises. As the processes of exorcism begun, the woman’s devils began to speak. On occasion, the devils ordered the woman to choke or drown herself. Although Drage appeared unsure of possession, noting that the patient seemed able to act normally at most times, he acquiesced in the diagnosis.

Hunter (1982) notes that this narrative appears to demonstrate double consciousness or multiple personality disorder, although clearly the patient spoke and acted within a cultural framework and appeared often in control. Drage noted that the devils spoke in a different voice to the patient and would order her to dance, which she did. Drage points out that recently an entire convent was overtaken by a similar kind of possession. While any psychiatric tome will claim the patient’s behaviour as evidence of mental disorder, as does Hunter in Three Hundred Years of Psychiatry-1535-1860, this can also be seen as extreme acting out in, for the patient, a possibly repressive and manipulative environment. Drage, as doctor’s today, concentrated on the patient and accepted her behaviour as subject to dynamic external agencies rather than an example of active negotiation between the patient and her environment.

A number of books spreading the philosophy of empirical thinking do not mean that such an approach was widely employed. Clearly another perspective was emerging, with emphasis on the brain as the source of mental health, most noticeable in the work of Thomas Willis (1660). In the 17th century the mind of course was rediscovered in the works of Descartes, and became then on a matter for analysis and debate.

Broomberg, in a triumphalist heat produced no doubt by the discoveries of the 1960s and 70s, believed that by the 17th century supernaturalism as a means of understanding physical and mental illness was giving way to rationalism. While on the surface this seems true, I hope to demonstrate in later books that rationalism may not be as clearly defined as imagined.

The history of madness, as I previously indicated, involves more than the history of those organisations set up to deal with the social consequences of folly, a term Foucault preferentially employs as it carries with it assumptions of reason, and attempt an understanding and cure.

DOMESTICATION AND GENTRIFICATION:

In order to better explicate the issues involved, I will also here look at ‘domestication’, an idea formed out of an archaeological perspective of the Neolithic. It was during this period that rapid, that is over several thousand years, urbanisation occurred. Cities emerged creating human corrals or pens. Within these, spatial concepts were formed, separating the city, a completely human environment, from the world outside of the city, denoted as wild and dangerous. From these long-developed notions we acquired ideas of chaos and stability, disorder and order. In The Myth of Mind and Consciousness I suggest that many of our present psychological and social traits were formed in this period.

Prominent in creating understanding of domestication has been Ian Hodder who excavated Catalhoyak in Anatolia, the earliest yet discovered town dating back at least 10000 years. Domestication involves the emergence of agriculture, thereby domestication of plants, animals and human beings. Plants were changed to provide greater stability and nutrition for humans, pigs, sheep and cows subjected to eugenics, producing often smaller versions of their wild cousins. Symbolism, painting and relief sculpture, expressed the ideas behind domestication by symbolically controlling the wild, evidenced by the portrayal of dangerous animals within Catalhoyak and the nearby site of Hacilar. Hodder (1990, page 9) suggests that the interiors of homes had, and of course have, representational values, for example: male: inner (back) death and the wild: female: outer (front) life and domestic. One consequence of this was gender roles and generic personalities. Burials take place within the dwelling at Catal Huyuk, demonstrating the need to control death. Until recently in Western societies, women have been associated with kitchens, the back of the house, while men often controlled the living room, the front of the house, symbolising domestic and public roles within society. In suburban England, the husband dealt with the front garden, although peripheral plants, such as roses, might have been within the woman’s domain. If a man attended to roses, for example, he would have been expressing female attributes. Such symbolism sustained a ‘natural order’.

Conversely, Hodder suggests that female reproduction was linked to the wild and danger. In fact, throughout ancient history, women appear to occupy the opposites of domesticity and extreme wildness/danger. For example, Lillith and Eve, Inanna, who represented sexual love and war, and also witches. The threatening nature of women in Greek plays, can be ascribed to their identification with the wild, deep, primeval, uncontrolled and uncontrollable forces, while in epics they are often presented as wives. This of course is a considerable subject that doesn’t necessarily lend itself to simple viewpoints.

As state apparatus grew, based upon order, it was necessary to eliminate or marginalise its opposite, which was threatening to both state and society in general. Whereas in medieval times, madness, with its several variants, was probably tolerated as part of the human condition, with the growth of the state in Europe, especially France, it became subject to control and restraint. The mad began to exist outside of society, becoming un-or-non-human, part of the ‘wild’, resistant to conformity and also non-producers. Over time a distinction was made between being normal and being abnormal, symbolised by mental hospitals. Doctors acquired, almost by default, roles constructed upon authority and order, especially in the defining and treatment of madness.

In archaeology, post-sessessonal ideas are also concerned with the symbolic meaning of artefacts, spatial symbolism and how urbanisation constructed human psychology by introduced concepts of privacy and individuality. Although psychology, as just one example, tends to perceive human behaviour as subject to interaction with other human types, this may nevertheless present a limited approach that has as much to do with structured professional learning as with the reality of human minds and motivations. From the beginning of recorded history urban landscapes have played an important role in shaping human psychology, ensuring domestication of our specie as well as segregation into classes and roles. An individual’s built environment can determine their behaviour. A prison, for example, predicts and encourages certain behaviour of both prisoners and wardens. Like a frame around a painting, it shapes our views. The prison, and asylum, represents state control and order. Although functionalism is itself limited in its perspective, it should also not be ignored when attempting to understand the emergence of modern concepts of mental illness.

London, for example, substantially changed during the 17th century from a city where rich and poor often inhabited the same space, to one where the rich were segregated from the poor. This involved the creation of the city’s suburbs, where the well-off began to reside. In medieval times the areas outside of the walls were largely inhabited by the poor and also by criminal elements, and in urban centres, such as Norwich, the city’s boundaries emphasised different mind sets, of stability and continuance, hard work and wealth, and instability and impermanence. The Domesticity and Wild dichotomy. By this reasoning, the way to contain the wild, criminals, rebellious or mad people, was to contain them outside of urban centres or, if within, in buildings that were little more than roofed walls.

By this reasoning, it is not surprising that fairs and the theatre took place outside of the city boundaries, although of course there are equally reasonable alternative considerations such as crowd control and the Elizabethan fear of mobs. Of interest is the fact that until recently those areas to the East and South of the city, were notoriously areas of criminal activity and for immigrant, usually marginalised, groups. London’s green areas throughout the 17th and 18th century became subject to increased control, with unruly elements prevented from entering Lincoln’s Inn fields, for example, and these areas became civilised or gentrified. While in London the congregation of the wealthy in the western part of the city, Piccadilly, Holborn, can be explained as due to their desire to be near the court at Westminster, it was also a consequence of the urbanisation of landed gentry, and the identification of gentility with large urban open spaces. In such Brave New Worlds, criminals and mad people would not be wanted, bringing into such civilised spaces wildness, disorder and fear.

Although Foucault’s major thesis concerns opposing reason/unreason, the gentrification of Europe may also have played a major role in views of and treatment of madness. Within this social and intellectual construct, wildness was placed well out of sight, and gradually, more and more, including emotional excess, was re-constructed as wild and dangerous, requiring control.

In London, during the 17th century, Gregg Carr (1990: 159) asserts that not only location constructed gentrification but also aesthetic factors such as spaciousness, newness of houses and clean air. London attracted the country gentry who often acquired one or two rooms in order to be close to money and marriage markets, establishing themselves in Westminster. Of course into this growing pool of gentry arrived professionals to tender to their needs and assume some of their behaviour and status. Although I have already considered this process, principally in the first part of An Unusual Power, I will look at it again through contemporary eyes:

‘Ordinarily the king doth make only knights and create barons or higher degrees: for as for gentlemen, they may be made cheap in England. For whosoever studieth the laws of the realm, who studieth in the universities, who professeth liberal sciences, and, to be short, who can live idly and without manual labour, and who will bear the port, charge and countenance of a gentleman, he shall be called Master, for that is the title which men give to esquires and other gentlemen, and shall be taken for a gentleman.’

Henry Kamen describes the term gentry as distinct from nobility in that the latter refers to a person’s outward rank, while the former refers to interior virtues that should accompany rank. Nobility, he comments, ‘could be bought and sold, but ‘gentility’ could only be inculcated’. Kamen stresses that the difference raised political issues about right to rule, whether by virtue of birth or through personal qualities. Although throughout the 16th century the argument predominantly lay with lineage, by the 17th century education and service began to take precedence, allowing thereby a greater place in government for merchants and civil servants. Becoming part of the gentry was already a route to becoming part of the ruling classes ensuring both a countryside and urban aesthetic that demanded order and peaceful surroundings, reflecting the internal values noted above.

The assumption of gentry’ values by modern society, and also by doctors, determined the nature of normality and thereby who is judged sane and insane. Although concerned with a much later period, Japonica Brown-Saracino, as editor of The Gentrification Debates, Overview: The Gentrification Debates, Routledge 2010, states that gentry implies a middle-class with shared recreational, buying, educational and housing values. This assessment can also be justified for the rising professional classes in 17th century Britain. Added to these factors, although not significantly different from the caste alliances of modern states, are construction of self, how individuals feel about themselves, and relationship to work or money. The relationship between gentrification and insanity/mental illness has become increasingly complex due to the introduction, for example, of psychotherapy. The spatial differences between gentry and poorer elements of 17th century London already expresses differences in power, and not just because of an increased closeness to the court. Those physicians closer to the court would express a power differential from those distant from the court.

Of importance to the establishment of gentry status were appearance, possessions, habitation, looks and dress, education, deportment, and these can be compared to the wild appearance, lack of apparent concern with goods and location of the insane. The gentry affect a calm method of talking, intent on elucidation, while the insane babble and rant. The gentry are emotionally ordered, while the insane are passionate. This of course simplifies much of the modern experience, but is symptomatic of the Early Modern World.

CONCLUSION:

This brief introduction to insanity in earlier periods and the present, views it as symbolising sexual excess and emotional excess, incongruent response, and corresponding to any behaviour that takes an individual out of the community or opposed to the community. Since the earliest periods of urbanisation, humankind has been subject to pressures of domestication, formed by space and the attitudes suited to re-constructed space, for example how the local authorities in Norwich established human behaviour within the city by ejecting those displaying unsuitable behaviour outside its walls or how London constructed zones of behaviour within its walls, establishing preferred behaviour in the western parts of the city. Extreme behaviour is tolerated within a dominant context or narrative, but not tolerated if the behaviour is exclusive. In many medieval stories, the mad, those not included within the dominant social ideal, exist in woods and caves: in the wild, alongside outlaws.

While Galen, a Greek working in Rome, believed that humoral imbalance caused madness, Hippocrates seems not to have utilised a separate view of madness, bracketing nightmares and excessive, erratic behaviour together. In medieval times, madness was connected to sin and penitence, and involved acceptance or recognition of God. Demonic possession and madness were seen as the same, the cure often involving various kinds of punishment. Throughout these periods, instances of modern day psychiatric typology is difficult to find, while many of the attitudes of earlier periods are evident in modern psychiatry.

Madness depicted in Early Modern literature, usually throws a light on the behaviour of others, highlighting pride and sinfulness for example. The mad often expose the corruption of society and like Hamlet point to higher ideals, better forms of behaviour and glimpses of a more evolved self. While this can be seen as one side of humanism, the other side envisions those without reason, within society, as being like beasts. The wildness of those outside of society is thereby internalised, and madness is viewed negatively. The ugliness of wildmen and witches is transferred to the insane. The emergence of widespread gentrification requires that the insane, as with the poor, dirty and criminal be removed from specific localities and situated within parts of the city away from its civilised aspects. Images of the supernatural world appear to have fed into later images of the mad, coming to agonised fruition in later asylums and modern-day tabloids, both presenting the mad as uncontrollable, lustful and violent.

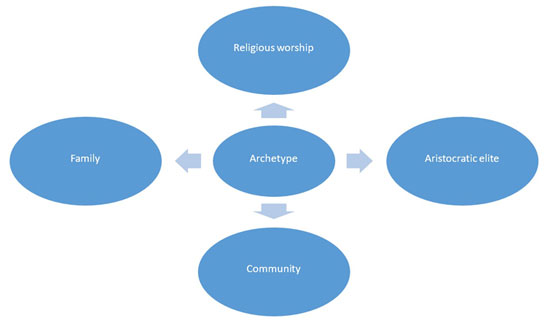

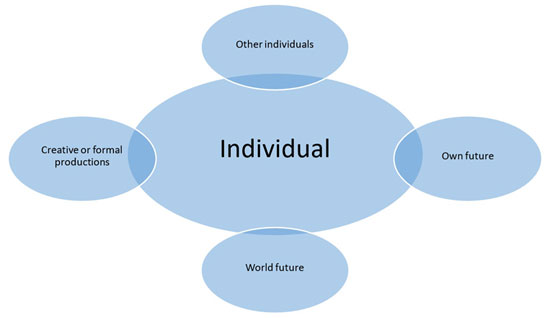

The autonomy of Hamlet expressed a psychological change that created the concept of mentality, or mental energy. Before, individuals dealt with and understood the world through a number of interrogators, such as priests, holy books and various interpretations of god. Thereby individuality was barely present except where status occurred, usually in relation to a dominant figure, such as a king, or through the publication of written material bearing claims of authorship. Mental energies were directed outward, expressing dependence on or intentions distinct from the group. Once human beings began the long lasting internal conversation with being, the gathering resonances created self-consciousness, the relationship with oneself, and forces that became the fodder of modern psychiatry.

Energies are directed outward, being resolved or not by external factors and forces.

Energies are directed outward, being resolved or not by external factors and forces. The individual’s energies are not contained by external factors and forces but are engaged exponentially with life-experiences, creating thereby abstractions and greater energies.

The individual’s energies are not contained by external factors and forces but are engaged exponentially with life-experiences, creating thereby abstractions and greater energies.

By the later 16th century, definitions of madness involved the law, and, also, often the state. Although Sedgwick (1982) holds that madness exists within a normative frame or ideal state and is not subject to context, he assumes that there is a direct link between the concepts of medieval and Early Modern views of madness and the present. He also invests observers and treaters of lunacy with a similar ideal form. A thought experiment may help at this juncture. If someone in our present society, if the reader is in the same society as the writer, has a fixed fascination with balloons, buying thousands, talking of nothing else, a physician would probably define such a person as suffering from mental illness. If the individual with such an apparently compulsive fascination suddenly enters another world where balloons are valued and employed everywhere, say for currency, their behaviour will occupy a normative frame. The physician, if they cannot develop a fascination with balloons, could then be deemed mentally ill.

This paper has described madness as a consequence of paradigms of wildness, the natural world, and of urban life representing order, but that does not invalidate its actuality. Although many of thinkers, for example Laing, Szasz and Foucault, from the 1950s until the 1990s denied the existence or suffering of mental illness, this is not really an acceptable position. It exists but perhaps not to the degree and in the manner physician’s claim. The brain can become diseased, suffer faults at childbirth or before, or simply function in one way or another differently from the norm. But otherwise, the descriptions of present day psychiatric diagnosis fit more closely cultural construction. This work focuses on physician’s power, as noted by Foucault, and colonisation of mad treatments and thereby physician’s mind models, contrasting these with present philosophical and neurological viewpoints. How did physicians’ ideas of mental illness come to be the norm, and how much truth does the medical model contain?

- A Strange Place - December 5, 2025

- The Puppet Dance - August 15, 2025

- Until I Stopped - April 23, 2025