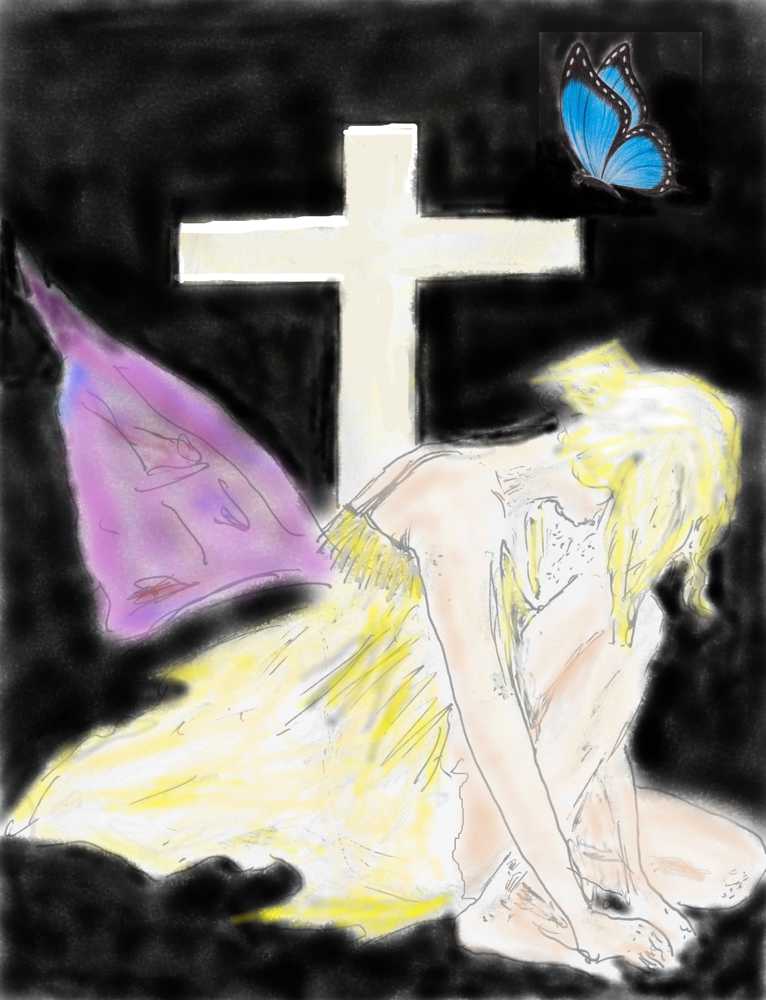

Metamorphosis

written by: Nyema James

“Ellie has the soul of a butterfly.”

“Ellie has the soul of a butterfly.”

I realised how preposterous it is to say such a thing. The belief fits better at a natural therapies seminar in Fremantle, where couples align their energy fields. But there it is; Ellie has the soul of a butterfly, and it’s not something I’ve always understood.

From the moment she could walk, she sat each morning in our front garden watching butterflies, holding out her small chubby hand, enticing them to walk the length of her arm. She babbled to each of them, holding them close to her face, her eyes wide, soft and gentle, tilting her head one way then the other, listening for their replies. They clung to her skin, wings slowly oscillating in response.

My husband, Isaac, and I have a photo of her with five butterflies atop her head, wisps of hair across her face, and her arms outstretched, beckoning others to join her. It was my favourite photo, that is, until that miraculous day.

For her tenth birthday, Ellie asked for a bright blue cotton dress. She pressed her hands against the shop window, stared at it, and whispered. “That’s it, Mum. It’s the colour it likes.” “The colour what likes?” I asked. “A special butterfly,” she said and would say no more about it.

Her grandmother made her a pair of silk wings almost as large as her, with bright splashes of crimson, yellow and topaz. Ellie placed lilac sparkles around her blue eyes that she’d darkened with mascara. She put a circlet with tiny black antennae atop her head and dotted her hair with freesias and daisies. Except for school, that’s how Ellie dressed from that day forward. Even at school, Ellie wore sparkles and mascara. I had notes from the teachers about it. My reply to them was, if that’s the worst thing Ellie does, then we were blessed. I got several more notes, arguing that it encouraged other students to wear make-up. I wrote back advising them to take it up with the other students’ parents. In the end, I think they just saw Ellie as a creative child and me as an uncooperative parent and let things slide.

Ellie met Ulysses when she was eleven. I saw the boy standing with his mother, watching the kids file into the schoolyard. Large patches of dark scaly lumps disfigured him and extended over his arms and legs, giving him an unfortunate grotesque appearance. Passing children stared and commented to one another. Ellie was drawn to Ulysses. As soon as she alighted from our car, she walked to him and held out her arms. Ulysses turned to his mother and back to Ellie, her arms still outstretched towards him. Ulysses tentatively placed both his hands covered in skin lesions into hers. His mother, her mouth agape, looked at me and smiled. Ellie and Ulysses walked hand-in-hand into school.

That’s how it was to be from then on. Ulysses and Ellie were always together. His parents, Greg and Anna, came to be friends with Isaac and me. Our conversations inevitably turned to Ulysses and Ellie.

“He has benign tumours that affect his skin and nerves. He’s in terrible pain and can barely walk,” Anna told us. It was painful for her, I could tell. She teared, and turned to Greg, who placed his hand on hers, his lips pressed tightly together.

“The tumours keep growing,” Greg continued. “It’s unbearable to watch him look at himself in the mirror. He told us he’s an ugly monster. I tell him his skin might be rough, but he’s a beautiful boy. He has no other friends at school. They all think he’s grotesque, and he frightens the little ones. Ellie is the only one who sees past his skin.”

“I am so grateful to Ellie,” said Anna. “What a curious and beautiful child she is, with a wonderful soul.”

“What can be done for him?” I asked.

“Nothing, Eleanor,” Anna replied. “The tumours are swallowing him and now affect his breathing.” Greg and Anna looked at one another, their hands tightly clasped together.

Most days, Ulysses visited Ellie. They sat in our garden, drawing and chatting. The tumours gradually took their toll on him. His face became severely distorted, and no longer could a patch of normal skin be seen anywhere on his body. Several lesions partially obscured his vision, and his lips and tongue developed lesions that made it difficult for him to talk.

The month before Ulysses died, Ellie asked me to take them to the Natural History Museum. “I have something to show you,” she said to Ulysses. He held Ellie’s hand and walked painfully and slowly through the entomology section, past the rows of beetles, before stopping at a large, magnificent butterfly. Its wings, fourteen centimetres across, were the most iridescent blue I’ve ever seen. Its long antennae extended from a sleek body.

“This is the Ulysses Swallowtail butterfly,” she said. “It comes from North Queensland. They’re not seen in this valley.” Ulysses tilted his head to see past the lesions. “It’s called Ulysses?” Ellie smiled. “Look how beautiful it is. The males like bright blue because they think it’s a female. Now, look just below. Can you see?”

“A cocoon?” he asked. “No, it’s called a chrysalis. See how rough and lumpy and misshapen it is. It has debris mixed in so it can camouflage. The outside may look rough, but what lies inside is incredibly beautiful.”

Ulysses studied the chrysalis and back to the magnificent butterfly. “It takes four days for the butterfly to break free of the chrysalis. Then it will rest, moving its wings slowly in the breeze, until they dry and harden. It knows what it must do before it dies and joins the universe.”

A lump formed in my throat as Ulysses took Ellie’s hand and nodded. Three weeks later, his breathing became laboured. I called Anne and Greg every day. Ulysses demanded that he die at home, in a chair, by their garden, where he could watch the butterflies.

Ellie remained with him during his last days. I visited on the day of his death. We sat around him as he struggled for each breath. As the end neared, Ellie gathered several butterflies and placed them on Ulysses’ head. We sat quietly. Waiting.

As the sun commenced its dip below the horizon, Ellie stood and recited.

“When the summer heat

Ceases to shimmer

Open your eyes

And give the call.

They will come.

When the last rays strike the eucalypts

And the cicadas cease their song

The air will thrum

Calling back to you.

I shall wait

When the sea breeze rises

Cast off your past

Harden your wings

And Take to the air

You will find me.”

Greg and Anna whispered to Ulysses and touched his face. The cicadas hushed and the butterflies stilled. Ellie and I stood silent, sentinels to Ulysses’ passing.

We returned home, and Ellie went to her room. Isaac and I gave her some time to herself. After thirty minutes, she emerged.

“Dad, do you have any copying paper? Like, do you have a few reams?”

“Sure, Sweety. What do you want with so much paper?”

“I’m drawing,” she said.

At midnight her bedroom light was still on. We checked on her; paper everywhere, pictures of butterflies, hundreds of them. Ellie didn’t look up, she just kept drawing.

For the next three days, Ellie didn’t leave her room except for food and more paper. On the day of Ulysses’ funeral, Ellie emerged in an iridescent blue, thin cotton dress that fell to her knees and followed her tiny figure. Her long blonde hair was dotted with blue and purple pansies, with two tiny antennae poking through. Large silken wings shimmered in gold and aquamarine. Knee-length socks, one solid blue and the other red and white striped, emptied into multi-coloured loafers. Thick mascara accentuated her blue eyes, and crimson and lilac sparkles spiralled from her eyebrows to her cheeks.

Isaac inspected her. “Ellie, I’m not sure that’s appropriate for Ulysses’ funeral.”

I patted his shoulder. “She’s perfect.”

Ellie picked up her school bag.

“What’s in the bag, Ellie?” I asked.

“Drawings.”

I looked at Isaac, who shrugged. “Okay,” I said.

“After the funeral, Mum, I want to walk home. Dad, will you come with me?”

Isaac nodded. I felt a tinge of envy that she hadn’t invited me, but Ellie was an enigma that only the butterflies understood.

Ulysses’ funeral was a simple affair, held in an old church not more than a kilometre from our house. Ellie, his only friend, stood at the back.

After the service, Isaac and I walked with Greg and Anna out of the church. At the exit, they broke into a smile. Ellie had placed scores of butterflies on the church door, along the path and over the sandstone fence. She stood waiting for her father.

The funeral party drove back to our house, where we hosted a wake. Isaac arrived some thirty minutes later. His eyes were red and puffy. Every ten metres, Ellie had attached a picture of a butterfly to a post. The beauty of that act touched him deeply.

“Where is she now?” I asked.

He pointed out the window. Ellie was covering every centimetre in pictures of butterflies. Over the lawn, the fences, the gazebo, the walls of our house. Butterflies in their thousands. When she was done, she stood in the middle of our yard. Motionless. Waiting.

“Is Ellie okay?” Anna asked.

I embraced Anna. “I think she’s calling to Ulysses.”

The afternoon wore on, but Ellie remained in our backyard, motionless.

“I should call her in,” Isaac said, “she’ll get dehydrated.”

“Leave her. She’ll come in when she’s ready,” I said.

The sea breeze sprang up, and the sun began to set, giving relief from the sweltering heat.

Anna came over with a smile. “You have a butterfly on your head, Eleanor.”

“Oh really? How poignant.”

Then there was another.

“Oh my God.” A guest pointed out the window. We could hear a purring sound growing in intensity until it became a roar.

“What’s happening?” I shouted.

Isaac stood with mouth agape, staring out the window. “Look. Oh, my God, look.”

Ellie stood, her arms outstretched. They came. Butterflies in their thousands so thick they blotted the sky. They covered Ellie and everything in our yard, shimmering with colours. Greg wrapped his arms around Anna. They were sobbing and laughing. Isaac and I were too.

Anna turned her face to Greg. “What could this mean?”

Greg brought his hand to his mouth. “Oh, God look, Anna. Oh, dear God.”

Ellie raised her right arm up and pointed her chin to the sky. A single butterfly, larger than I’d ever seen before, its iridescent blue catching the last rays of the sun, fluttered on the sea breeze and landed on Ellie’s outstretched hand. She smiled and brought it to her face and kissed it.

We all held each other, weeping, and watched what Ellie had known all along.

That was ten years ago. It’s curious that scores of butterflies continue to be seen fluttering over Ulysses’ grave. Perhaps it’s the freesias that grow in abundance around the grave. Perhaps.

Ellie completed a degree in environmental science and became close friends with a boy, called Skipper, who had a form of autism. Isaac and I sat with the boy’s parents, watching them receive their degrees.

At the reception that followed, Skipper’s mother said, “I am so grateful to Ellie. Skipper never spoke to anyone. She’s brought him out of his shell.”

Ellie, hearing this, said, “It wasn’t a shell; it was a chrysalis.”

- Discord - December 8, 2024

- Dispensing Freedom - June 25, 2024

- Metamorphosis - April 4, 2024