Musings Of A Reluctant Neo-Luddite

written by: Louis Gallo

AUTHOR’S RATIONALIZED PREFACE

My first thought when writing this piece was to let it all hang out not in a stream of consciousness but more of a gush then return to it and edit it structurally so that it would follow the requisites of a more formal essay. On second thought, I decided to preserve it as it was originally written, organically, to expose how the writing process actually works, to expose the writer’s raw mind (not that anyone is or should be interested). Perhaps the real reason is that I simply felt too lazy to engage in the normal, onerous task of wholesale editing. Whatever. So, for better or worse, here we go.

IN MEDIA RES/A NEW DISEASE

I have taught in varied universities my entire life and have by default beheld the changes wrought by technology as the years progressed.

Just today, because I teach online as a result of the pandemic, I wrote an email to one of my current classes with an attachment. When I pressed SEND, I was alerted by a message that I had no permission to perform this action and my attachment could not be saved. And yet the email went through to my SENT MAIL FOLDER. So, what ho? That particular glitch had never happened before (though there were many others along the way). And while this seems a minor technological issue, it does cause a moment of intense panic in the user. What is wrong now with my email system? Is it my computer? My ineptitude? Will I have to call Tech Support? And all the rest of what I now dub “computeritis.”

The introduction of computer technology into the world requires the creation of a new set of specialists—the tech corps. It has also introduced that new disease: computeritis. Most of us have no idea how a computer works or how to repair it when it doesn’t. Most of us live in a kind of low-key dread that tomorrow something may fail—the mouse, the keyboard, the screen, the operating or memory system, the hard drive, the software . . . worse, the manifold virus protection services. We keep in mind that the tech specialists are there, a phone call away. (Cell phones, another issue.) We become supplicants to these near holy technicians who, like medical physicians, just might cure us of whatever malady we suffer. We lose our sovereign selves to the collective technocratic intelligentsia who have us at their mercy, as writer Walker Percy might have put it a few decades ago.

[Just now as I typed these first paragraphs and tried to SAVE AS, the computer froze and SAVE AS disappeared as well as the document itself. I was finally able to retrieve it even as I had little hope that I would. Case in point.]

MIMEOGRAPHS, FOUNTAIN PENS AND WORD PROCESSING

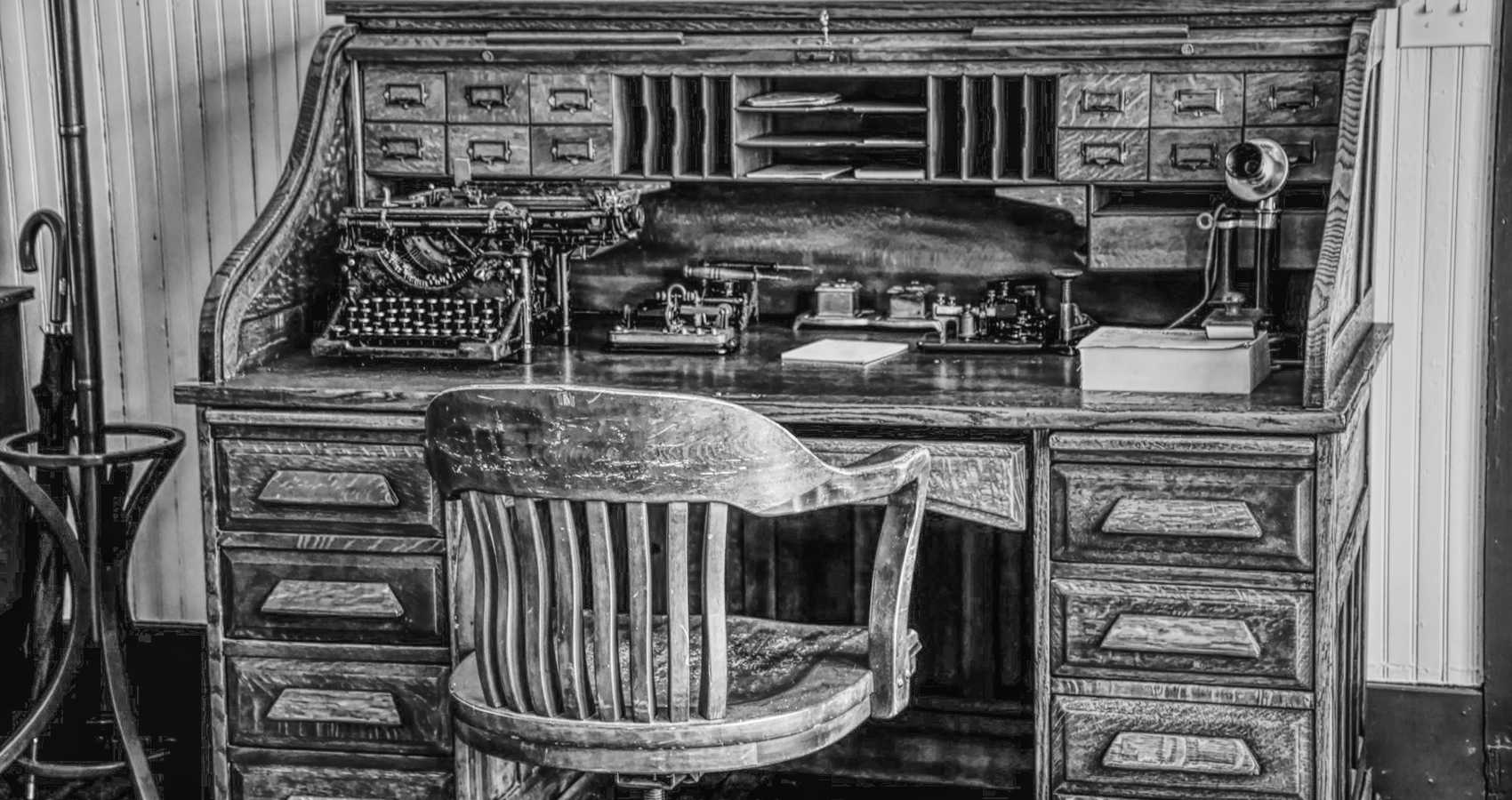

When I first started teaching as a graduate teaching assistant eons ago, at twenty-one years old, we had no computers, no cell phones, no copiers. To copy documents, we used mimeograph machines which you cranked by hand. The copies came out a kind of iridescent purple. And, of course, we got high smelling its strange, intoxicating ink. Decades later, academic departments invested in copy machines, which were great at first; you could print multiple copies of tests, syllabi or whatever in no time. Then, as technology “improved,” copy machines became so complex with so many mostly useless functions that I personally ceased to use them altogether. You needed a password, you needed to know which of the myriad buttons to push, and if you pressed the wrong button (button is not quite the word since buttons are mechanical whereas the new “buttons” we endemic, digital gizmos that you merely touched). No highs either sniffing the old mimeographs. Luckily, I guess, we could send attachments to students or to whomever and they could make their own copies.

But, again, digital attachments are a different story. At first, it was easy enough. You typed a document, pressed save-as to desktop, then attached to the email via the paper clip icon. That too has become more complexified with the introduction of OneDrive (whatever that is) and the Cloud. When I edit student papers that arrive by email via the Cloud, I cannot open or edit them. I presume they get lost somewhere in the mystic haze. So I must now create very meticulous instructions on how to send documents to me—create the document, save as to your desktop, and attach via the paperclip icon; send in MS Word only. Dreamily, as I open the attachments, I recall the old days when students turned in physical papers and I edited them with a pen. Some might say that all that paper was a drag; maybe, but it sure was easier and more reliable and personal.

The one absolute advantage to computers, to my mind, is word processing. I started out decades ago on an Underwood mechanical typewriter. What a horror, all that fuzz embedded in certain portions of the keys—any letter with loops. And the inevitable changing of ink ribbons, always tangled, always messy. Your fingers became black and red. Soon we graduated to electric typewriters (I had an Olivetti, on which I typed my doctoral dissertation while renting a mobile home in the town where I had been offered a job as an assistant professor at the local state university). The main flaw with electric typewriters was the white tape you had to use to correct typos—later machines contained built-in whiteners that required merely pressing a backstroke key. I did not have such a machine, so typing remained a major, onerous task. Back in the late 1980s/early 90s we could all transition to word processing. Took a while to learn how to use, and what confounded me most was the actual creation of space on a page, which seemed uncanny to me—sort of like the original creation of space and time by the Big Bang.

I started out with Wordperfect, a fairly easy program to learn. Within a few years the Microsoft conglomerate drove Wordperfect underground and one had to then convert all Wordperfect documents to MS Word. The transition never worked well—it created all sorts of hieroglyphics, structural extravaganzas, deletions, et al. MS Word has by this point become hideously complicated and deranged. Ever tried creating then paginating a table of contents? Try it for an exercise in the gnashing of teeth. It’s a technological marvel that it can be done at all, no doubt, and I eventually learned how to do it, though I will shudder if I ever have to again.

Until my mid-to late twenties, I painstakingly wrote everything by hand using a Parker fountain pen, after which I would transcribe into type with a typewriter—or, better yet, pay someone to transcribe. Until it became too expensive at five dollars a page. I am a widely published writer, and I write something, good or bad, every day. You could call it an addiction. So how thankful I felt to access word processing. If only it had come earlier when I was in my youthful twenties. But to so regret is how I imagine grandparents must have felt when they purchased their first Model-T. If only it had come before the horse and buggy.

I no longer write anything by hand and, in fact, cannot even decipher my own early handwriting. Thus I have stack after stack of hand-written manuscripts stored in a box in the attic. Word processing, despite my caveats, is so much easier and one can discern instantly how the poem or story, or essay will look in print. And on that point—before the onslaught of online journals and magazine, we writers sent out manuscripts by snail mail and return postage (SASE’s) included. We waited for months for acceptance or rejection and sometimes received no reply at all. Our publications came in physical contributor copies via the same snail mail procedure. At first, we viewed online journals with suspicion—not nearly as credible, official or genuine. Quickly, all that changed, and many online journals now surpass their print counterparts which are rapidly going extinct. Is this good or bad? Who knows? No more return postage, though a platform called Submittable has led many online publishers to charge for submissions to help pay the costs of Submittable. I rarely submit anywhere that charges a fee. It’s a sure-fire way to lose money given that the acceptance rate remains one in ten.

If only we could maintain word processing without the rest of the irrelevancies that plague computers and online work. We would still need home printers, another later invention during my lifetime, unthinkable only a few short years ago. But it would mean back to snail mail and physical journals. So go figure. While I am a neo-Luddite in general, I truly appreciate the dazzling improvements in the field of writing and publishing. But what about email? No more letter writing, alas. I preserved a large box of physical letters sent to me through the years in still another box in the attic, which every now and then, I lug down and re-read when afflicted with nostalgia for the past. Thing is, letters were slow, both to send and to receive. Which gets us into the question of speed versus relaxed and unhurried. One thing computers have accomplished is accelerating time itself. Email is instant. No stamps. No waiting—unless a recipient chooses not to reply. So far, MS Word has proved easy enough to use, but I see complexity sneaking in there as well. Multiple options, auto-corrections (almost always utterly useless and annoying), encryptions, Excel and all the rest of it. Early printing was halcyon; original email without accompanying, confusing options seemed heavenly when all you want to do, in the first place, is print, and, second, send and receive. It’s the ever-increasing complications that induce both reader and writer unfriendliness. Einstein used to say that the simple equations were the most reliable: e=mc2. Without email, I could not teach with Zoom, which I mentioned I have done since the beginning of the pandemic. I communicate constantly with students and receive their manuscripts via email.

ZOOM AND HAM RADIO

So Zoom may prove another plus for computerization. It took a friend of mine and I (he also taught with Zoom before retiring) much agony and sweat just trying to figure out how to use it. I still only know the basics, but they are enough for me to conduct classes. I don’t desire to know anything beyond the basics. There are always glitches with Zoom as even my young students quickly remind me. One can never feel certain that it will work, that your microphone will function (my friend told me that during one Zoom session, his microphone didn’t work; he had to turn off the power to the computer and HOPE that such drastic action would activate the microphone—which, lo! it did!) But it could just as easily fail at such restoration. Hence, further computer anxiety, which I believe we all suffer now; is constant and vexing. The question becomes—it such dread worth it? Is technology worth having at the cost of mental health and peace of mind? I assume it depends on how adept you are at understanding and using computers. Most of us can use computers as we drive cars, even if at a primitive level, but repairing (along with cars) begs another story.

And here is that other story. From thirteen to eighteen, I worked a ham radio rig, way before the dawn of the internet. My father and I built the receiver, the transmitter and an oscilloscope on which we could practice Morse code (after all these years, I can never forget the code). We also built radios. These were pre-transistor and printed circuits. We used vacuum tubes and varied radio parts like color-coded resistors, electrolytic capacitors, condensers and rheostats. We soldered these parts, including the vacuum tube holders, onto a chassis. For the amateur radio transmitter, we used massive mercury vapor tubes that flickered and hissed in the dark as they facilitated code transmissions all over the planet. I worked in strange places I had never heard of them, including Ukraine, the Archipelago of Sao Thome, and countries that no longer exist like Southern Rhodesia, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. But the point here is that we could repair our equipment easily ourselves. To test vacuum tubes we drove over to the local Katz & Besthoff, a super pre-Walmart drug store which had a tube testing machine. If bad, we simply bought a new tube to replace the old one. If a resistor or condenser or switch failed, we unsoldered them and soldered in new replacements. There was no technological anxiety except slightly when the ionosphere dipped or lifted making it difficult to transmit except locally. It all changed abruptly with the advent of transistors, little plastic beads that replaced vacuum tubes. I remember my father sighing–“it’s over, this is the end.” Printed circuits followed shortly. Only professional engineering wizards could handle both transistors and printed circuits.

The same is true with automobiles. Computerized vehicles can be hacked and the ordinary Joe can no longer repair his own vehicle. Recently, one of my headlights burned out and I tried to replace it (as I used to do often enough). But one now needs a special wrench to unscrew the entire apparatus simply to replace a headlight. I had to drive to an auto parts store to find someone with that wrench who could do the job. And the tires on my latest SUV require nitrogen air if the pressure drops. No more simply filling up the tires with regular air at the local service station. Must return to the dealer twenty miles away for refills. So it seems “advances” in technology now make difficult every aspect of life. Perhaps this was always the case as societies progressed, but the older mechanical advances were easier to understand and could be dealt with by ordinary people. Digital technology now demands corps of highly trained professionals. Constant “improvements” which always necessitate re-learning what you thought you had mastered assure mental havoc.

CELL PHONES, CYBERSPACE AND HACKERS

So let’s move on to cell phones. For years I have used a simple LG flip keyboard model which has served me well whereas everyone I know now craves a smartphone. If you walk on my campus anywhere, you will spot every student fiddling with these devices as they walk or loaf on benches or sit in classes. I have no desire for the internet on my phone; nor do I want to metamorphose into some cyborg always connected. (Same with laptops—I hate them and still use a desktop.) Well, I began to receive messages from my carrier earlier this year that my phone, backed by a 3-G network, will be decommissioned by the end of the year because of the new installation of a 5-G network (the two smartphones of my daughters will also be so decommissioned). So I bought a simple, very easy to use Jitterbug and have learned how to use it, though I have not yet transferred my phone number to that device. I made several attempts to contact my carrier, always to no avail because their site doesn’t work (!). I finally received an email proclaiming that they were sending me free of charge a similar phone (it wasn’t—it was a piece of caca) and that they would activate it within thirty days. I did not order this phone yet on the paperwork it was stated that I had indeed ordered it). I did not want it activated. I would stick with my original phone until I transferred to Jitterbug. I tried but failed to get a return address from the company but no one I spoke with could provide that information. There was no return address label included. So I mailed it to the address from which it had come. As I tried to track the package, all that I could discern was that it remained in transit, for at least two weeks. I have no idea if it will ever be actually delivered. My daughter has a high-tech friend who told her that the 5-G business was a scam to make money by forcing phone users to buy new replacements at astronomical costs. I have absolutely no doubt about the validity of that claim. At any rate, I called the carrier AGAIN to inform them that I did not want the woeful replacement phone. It took forever to speak with an actual human whose broken English I hardly understood. I had to wade through dozens of robots who all provided irrelevant information and options. I felt my blood pressure rising fast and just about gave up. This is what it has come to in our new and improved phone technology system. Customer service is a joke. I long for the days of Ma Bell.

Nor does this take into account all the drivers who continue to text as they drive. Just look around as you cruise. You will see them looking down at their phones and texting. How many car crashes have they caused? Sure, it’s illegal to text as you drive, but who’s counting? Of course, there are numerous advantages to cell phones: instant communication, wherever you are, which is great for emergencies. No more scouting around for rancid phone booths that smell like vomit; no more depositing coins into a slot—you never have enough. I recall once when my second wife and I were driving along the interstate from New Orleans to Hattiesburg, the drive shaft of our vehicle came loose and clanked onto the road. We had to walk a mile or so, I carrying our baby child, to the next town to locate a booth and make frantic calls for relatives to drive over and help us out. Nevertheless, if given the choice, I would return to those days when things were simpler and easier. The anxiety induced by a few incidents here and there seems preferable to the onus of constant perplexity over cell phones. We managed, after all, for decades in that fashion.

And what about the danger of all your information residing somewhere in cyberspace? Your bank account for example. I do not want my data in cyberspace though I seem to have no choice in the matter. Hackers are out there non-stop trying to break into bank accounts or whatever sensitive information they can find. Yes, it is nice to be able to make payments or review your accounts any time of day or night, but is it worth the risk? In the old days of yesterday, you could walk into your bank and transact business. Now, with the constant mergers of financial institutions, you must call a central office perhaps thousands of miles away from your home. And what then?—the same mostly preposterous phone menus, being put of hold, faulty connections, disconnections, humans (if you manage to secure one) whose broken English you can’t understand, et al. Given the risks and the annoyance, I would press a button to return to the days of yore, however slow and time-consuming they may have been. I see so virtue in speed for the sake of speed. Could be that what we all need is to slow down. Speed certainly induces cortisol, that ominous hormone that ransacks the metabolism. I used to wonder why so many of my students have been prescribed medications for stress. I no longer wonder. It’s obvious. Their lives are frenzied and non-stop. Back when I was an undergraduate, during registration for classes, we stood in line before hundred of tables for each department, signed up for classes on the spot and hoped those classes were still open. The teachers sat behind the desks and removed cards from boxes containing each class section. Now students register online—and while it goes smoothly enough most of the time, the glitches are abundant. And to repair a digital glitch is no small feat. At least with paper cards, you knew right away if you had been registered for the class or not.

CORRESPONDENCE SCHOOL

When I taught in-person courses, I set deadlines for the students to turn in their work. The papers were literal and I kept a separate manila folder for each class with each student’s work within. Now that I teach online, the “papers” take the form of digital attachments. It’s an altogether different feel not as friendly or intimate. And don’t even mention e-books to me. I regard them as abominations. I like the feel of real books, the older the better. I like their smell of vintage leather, the tooled covers, the temporal mustiness of the pages, the often gilded edges of the pages, and the sewn-in ribbon bookmarks. Not that I mind commercial hardbacks or paperbacks—anything corporeal, real. This brings to mind a summer job I had as a graduate student. I have already discussed my ambivalence about Zoom, something I could have not foreseen merely two years ago. I am astonished that Zoom works as well as it does, and it certainly facilitates distance learning. But there was once an alternative called Correspondence School. This was my summer job between semesters. The campus housed a quaint brick building off in the distance (its purpose scorned by senior faculty as lowly and ersatz) where I would arrive at eight a.m. every morning as an English correspondence school instructor. I had my own office off to the side of the director who sat stiffly in the large main room with her array of miniature cacti and sensitive plants. Alas, I can no longer recall the name of this elderly, very prim and gentle woman who taught me much about what was then long-distance learning. I can still see her face plainly enough and that vision always brings a smile to my face. She rarely left that desk except during lunch break. There was another room across from mine that lodged another instructor, this one in the Theater. Double alas, I can no longer remember her name either but still see her in my mind’s eye leaning against the doorframe of my office and chatting away.

She was always dressed in black (shiffs mostly) and never missed a chance to recite lines from Ibsen or Chekhov with flamboyant, theatrical abandon.

Meanwhile, I had to study. One course I taught was Survey of American Literature. I knew little about it aside from my field of Victorian, Modern and Contemporary. Student test questions were standardized and covered the entire swath of American letters from the earliest colonists to the latest work of Wallace Stevens and beyond. So to assess the answers of my students, I had to quickly learn the work of writers like Anne Bradstreet, Edward Taylor, Jonathan Edwards, Captain John Smith, Benjamin Franklin and the like, everything pre-Victorian, though I also know a good bit about the Romantics. I studied intensely and hard—it was as if I were taking courses in those early Americans. And I am forever grateful for the opportunity to learn about them. I became particularly enchanted with the bizarre life and writings of Jonathan Edwards, particularly his Personal Narrative. I came to despise the opportunist and crass pragmatism of Franklin, who stole many of his apothegms from the French but passed them off as his own. Anyway, when a student applied for a course (and there were many, all the time), the director would ship off the first test to the applicant; a course required about four of five such tests, each covering an era or sub-era in the literature (first test would focus on colonial, Puritan and federalist work). The student received the packet a few days later by snail mail and had a deadline by which to return the completed test.

The completed tests, when returned, arrived in thick, massive manila envelopes, each completed test amounting to thirty or more pages of not type, but handwritten answers. In some case, I spent most of my time trying to decipher the script. I would then apply what I had just learned to evaluate the answers, each receiving a letter grade from F to A then averaging those grades into a final letter grade for the entire test. I also had to comment on each answer, sometimes briefly, often at length. When done, I turned the completed papers to the director who stuffed them into a return envelope, affixed postage and dropped them into the outgoing mail unit. I assume the entire process from when a student first received the test to days later when my response arrived occupied at least two weeks of time. Nothing like the instantaneity of Zoom, but quite effective and formidable. There are alternatives. If I could return to correspondence school and ditch Zoom, you guessed it—I would choose correspondence school, however antediluvian. No computeritis ransacking the synapses except perhaps a fleeting worry that the Pony Express might deliver a package to the wrong address. I would, however, miss seeing the faces of and talking with my students even if in cyberspace. I had no idea what my correspondence students looked or sounded like. I gauged them merely by their handwriting and proficiency in English—which means I often had to correct grammatical, agreement and general usage mistakes with a red pen, though my comments arrive in black ink.

COVID CAME DOWN LIKE A WOLF ON THE FOLD (to rephrase Lord Byron)/THE HYPOCRISY OF AMBIVALENCE

We all know that the pandemic changed everything. As I write, we are nearly two and a half years into it and it doesn’t seem to be going anywhere even as the populace prefers now to ignore it.

But I still equip myself with KN95s, plastic gloves and hand sanitizer. My lifelong hypochondria does not help. I sense constant contamination and avoid people altogether other than my wife and two daughters, cat and dog. We have all been holed up in the house since the beginning of the onslaught. My daughters had to finish their advanced degrees online as well as their student teaching; my wife switched her teaching to online then retired just last semester when hundreds of thousands of other teachers across the country fled the field because of outright abuse by administrators and the political shenanigans of Don’t’ Say Gay and all the rest of it.

I recall the abrupt switch of my own in-person teaching at the university to online in, if I recall correctly, March 2020. And I have been online ever since. It has been quite a ride for one who does not trust technology and who can use it only in primitive fashion. I have never mastered the PDF, for example. When I need to sign such a document, I authorize others in the department to sign for me. I understand the necessity of PDFs, but I truly despise them.

So it is quite hypocritical for me to declare that the world would be better off without computers. Nevertheless, if I could press a button and get rid of them I would instantly, without hesitation, despite their absolute necessity (for me) during the Age of Infection. I use them constantly to submit documents for publication, to teach online, and to socialize online since I no longer socialize otherwise. Socialization blends with teaching in a curious way. Pre-pandemic, my colleagues and I would often set up poetry readings among ourselves and our students; during the second semester, we invited the winners of the writing contests to a grand (refreshments included) public reading.

For the last two years, we have held this reading online via Zoom. Most of my colleagues have returned to teaching in person, but given my age and risk factors, I remain isolated and online. The attitude now seems to be, ok, I will probably contract Covid, but that’s the break. My best friend, however, retired last year but contracted Covid somewhere and now suffers the long version. Medical experts inform us that twenty to thirty percent of cases will result in prolonged long affliction which can induce serious neurological damage.

Moreover, as I realized that in-person physical interaction with students was paramount for their continued education as well as my own, I created two Facebook pages called Poetry Jams. With their permission, I would and still post their edited poems on these pages. The pages have hundreds of members. Former students (some from way back) and current students as well as colleagues can post their work on the Jams. FB allows me to see exactly how many users (and who) respond to these poems. Some get few responses, some get up into the eighties and nineties—one never knows. In this manner, I can continue some semblance of socialization with my students from many decades. It does not take the place of literal interaction but given the wallop of Covid, it’s the best I can do. Even today when I meet Zoom classes, several students tell me that they either have Covid or have had it recently.

A friend of mine who read this essay said that he didn’t know where I was going with it and I replied that I didn’t either. I just let everything on my mind hang out. He (a professional writer and former professor) indicated that while I professed hatred for the ravages computers have wrought, at the same time I praised their virtues. Contradiction. I rely upon Walt Whitman’s response to such constructive criticism: “Do I contradict myself? Very well, I contradict myself.” Or Emerson: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds. . . ..”

I trust the assessment of my friend, a superb writer who has published many books and poems and essays, and, ironically, he too is a fan of Whitman and Emerson. In the end he told me to trust my own instincts with the piece. I well know that trusting one’s own instincts can lead you astray, but—and here is Frost—sometimes the path not taken proves the most auspicious.

. . . . Oh, I forgot to cover computer viruses (aside from medical viruses) and malware and phishing . . . another day, perhaps. I lost my identity to one of them. So I shall dangle my finger over the Luddite button and let it hover there for the nonce.

- Musings Of A Reluctant Neo-Luddite - July 22, 2024

- A New Theology: Divine Incompetence - April 23, 2023

- Halloween - October 25, 2022