Persistent Memories

written by: Simon Nadel

“Edward Perlson is working on the coronavirus.”

My mother didn’t specify whether he was working on some type of cure or instead working to strengthen the virus and perhaps make it even deadlier. Her eyes were unfocused as usual but her mouth was turned up at the corners in a slightly sinister grin, made even scarier by the bright red lipstick she had uneconomically applied. My father was, in fact, not doing anything to either eradicate or enhance Covid. He was upstairs napping. My mother could have a sherry at 4, he had told me. It helped with sundowning. I had no idea how we would pass the time until then.

It was 2:42.

“We’re in amazing times,” my mother said. “It’s the start of the twentieth century. We’re lucky to live in these times.”

“We are,” I agreed. After only three days I was out of ideas so I did a lot of agreeing and reinforcing. I nodded and smiled and went along with all of my mother’s delusional statements. I was pretty close to scratching lines in the wall to mark down the days until I could go home. “Do you want to see some pictures?”

I had shown them to her four or five times a day since I’d arrived. She smiled a less sinister smile. This one more resigned. From bad clown to sad clown. I went and sat down next to her on the couch, got out my iPhone and started scrolling through the photos.

“Who’s that?”

“That’s Asher.”

“Oh, he’s so big. What grade is he in now?”

“He’s a junior in college.”

“And who’s that?”

“That’s Hannah, mom. My wife.”

“Oh, I remember her. And who’s that with her?”

“That’s Asher, mom.”

“Oh, he’s so big. What grade is he in now?”

“He’s in college, mom. He’s all grown up.”

“And him?”

“That’s me.”

“Oh you look terrible.” She laughed and for a millisecond she sounded like her old self, like the mom who had been my best friend. My heart did a little loop-de-loop, then quickly reset itself. I felt silly for being so sentimental. She wouldn’t have liked that at all. My mother has always despised sentimentality as if it were a personal affront to her. There are a fair amount of commercials where dogs and people make each other feel better. They’re usually advertising dog food. I well up every time. I wouldn’t dare tell her that, even in her current reduced circumstances.

I showed her pictures of our dog and two cats. She smiled and made ooh-ing and ah-ing sounds and laughed a little more.

“Did you feed Muldoon? And clean her litter?”

“I did,” I said. Muldoon was their last cat. She died my senior year of college.

“And who’s that?”

Too quickly I was out of pictures. I could have just started over. It wouldn’t have made any difference.

“Edward Perlson is working on the coronavirus,” my mother said. “They think he doesn’t know but boy he really knows what’s going on.” She lowered her voice and leaned her head toward me. “You need to keep the windows closed to keep out the coronavirus.”

It was 2:48.

My mother said she needed to start dinner. I suggested a walk instead. She disappeared upstairs. I should have checked on her sooner but I was enjoying the brief respite. I heard water running, then the shower going on. I tried to play Spelling Bee but the middle letter was Z and I was tired and not feeling very focused. I got a few words and gave up. I stared at the window to see if a cloud of the virus was swirling around outside but it was so smeared with grime that I couldn’t really tell. I probably should clean the house a little more thoroughly while I’m here, I thought, though I knew I wouldn’t. My mother came downstairs wrapped in a frayed pink towel. Her hair was wet and standing up. She looked like a tiny baby bird that had fallen from its nest and would never be allowed back in.

“Mom,” I said, “you need to get dressed so we can go for a walk.”

She blinked a few times. “I need to start dinner.”

It was 3:12.

I finally convinced her to get dressed for a walk. She put on a yellow nightgown with flowers on it and a lot more lipstick. She’d drawn over her eyebrows in pen.

“Is this place fancy?”

“It’s just a walk mom.” I got her into her coat and sneakers and we went outside. It was a gray day and most of the leaves had already fallen off the trees. The neighborhood looked like a depressed mill town. It was like that movie Nobody’s Fool but without anyone as charming as Paul Newman or as wise as Jessica Tandy. The sidewalks were uneven. It was treacherous terrain, even for those not suffering from dementia.

“Edward Perlson thinks we’re gonna live here,” my mother said, “but he’s crazy if he thinks I’m leaving the city.” My parents never intended to leave New York City, but when Fordham wouldn’t give my father tenure it was only Ulster County Community College that offered a job. And my mother never stopped resenting him for it.

A woman raking leaves gave us a very big hello, the kind reserved for those clearly in some type of distress–the disabled, the enfeebled, the terminal, or the just plain crazy. “The people here are very nice but what’s lurking underneath?” my mother said far too loudly. “Edward Perlson is a fool. But I’ll let him think I don’t know what’s going on.”

We were halfway done with the walk, the same circular walk around the block we did each day of my visit. My mother pointed to a weather vane on top of a shed. “He’s watching us, always watching us,” she whispered.

A pitbull chained to a railing came lunging toward us barking ferociously. I was startled and almost lost my footing. Catching myself from falling made my sciatica shoot lightning bolts of pain through my hips and legs. My mother didn’t even seem to notice the dog. A scrawny guy was in the driveway working on his pickup. Why were all the men around here always working on their trucks? He looked over at me and my mother. He could have been 25 and he could have been 60.

“That’s a beautiful dog,” I said. “It seems kind of cruel to keep him chained up like that.”

The man of indeterminate age took a couple of threatening steps in our direction. He reeked of cigarette smoke. He was grinning. “It’s a she.”

“Well she shouldn’t be chained up like that,” I said, my voice coming out an octave higher than I wanted.

He took another step forward. I could almost feel the potential violence in the air, like a sudden cold breeze. He was pale and had a mangy goatee. He coughed loudly. I immediately thought of Covid. “Maybe I should unchain her and show you what she’s really like,” he said.

I steered my mother away from the unsavory man and his dog. “I fucking hate people who mistreat animals,” I said, more to myself than her. “I hope that dog rips his throat out.” Just saying it out loud made me feel better for the dog and for me, and maybe a little bit for the future.

“I’m going to visit my parents,” my mother said. “They miss me.”

“I’m sure they do, mom.”

“Is that our house?”

“Close, mom. It looks just like ours.”

Back at home, in the house that really was hers and not just a reasonable facsimile, I helped her out of her coat and sneakers. I hugged her. “I love taking walks with you, mom.”

“I need to start dinner. Edward Perlson is going to add coronavirus to the pasta.”

It was 3:38. I went to get the sherry.

We ate leftover chili for dinner. I had made it on my first night there. It wasn’t very good but it’s hard to cook in someone else’s kitchen.

My father was still wearing the big dark glasses required from his cataract surgery. He looked like an alien or just a frail old man in oversized sunglasses. “I really wish you could stay longer,” he said.

I tried to put on a cheerful voice. “The doctor said you’re fine, that you could even have driven today. And I really need to get back.” We both knew the second part was a lie, though technically, unless I wanted to go insane I couldn’t spend another day with my parents. I decided to double down. “I owe my publisher some pages. I just need to get back and get to work.”

My father just shook his head and took a spoonful of the not-very-good chili. Then he shook his head some more to emphasize how not very good it was.

“He’s right,” my mother said to him. “We need to get back too.”

“Get back to where?” my father said. He was mad at me and taking it out on her.

“I’m going to visit my parents. They miss me.”

“Your parents are gone,” he said, then added, as if to soften the blow, “they’re spirits now.”

My mother smiled sadly and shook her head. “This food is terrible. I’ll make something better tomorrow.” She had completely cleaned her bowl and her mouth had a ring of sauce around it. “We need to be careful about the coronavirus. It might be getting in through the windows.” She looked at my father as if only he knew what she meant.

I slid my phone out of my pocket and texted Patrick. I’m in town, Grab a drink later? It’s Adam.

He immediately sent back a thumbs up and wine glass emoji. Then added an OMG!!!

***

“It’s nothing like in your book,” Patrick said, holding his hand out to encourage me to take in the entire space. We were sitting at the bar at Ray’s. It was quiet on a Monday night. We had a bottle of pinot noir in front of us.

I was slightly distracted by the bartender. She had one of those faces where nothing quite fits together. Sexy ugly I think they call it. And she had the Lauren Hutton gap. I’m a sucker for that. And a tight tank top. She was probably in her early 20s, Asher’s age. Maybe I should take this part out.

I took a sip from my glass. I said the same thing I’d been saying since we first sat down. “It’s fiction.”

“Then why didn’t you change the names?” Patrick had quickly arrived at the point, his point.

I shrugged. The book was loosely based on my high school years. But clearly not loosely enough.

“You didn’t need to name the one gay character Patrick and then make him so pitiful.”

“I didn’t think he was pitiful. And it’s fiction. And nobody read the fucking book. Believe me.”

“I read it. My mother read it.” He refilled his glass. “And by the way, she really liked it.”

“That’s nice,” I said.

“Well why wouldn’t she like it? She comes off great. Not like her son.”

“Patrick, seriously, it’s fiction.”

“Well you certainly made yourself look pretty good. And 6 foot 2, really?”

“Jake is not me,” I said.

“Well he sure sounds a lot like you, with his whole holier-than-thou attitude.”

Of course he sounded like me. He was the me I wanted to be. The me that comes back to town, beats up some unruly rednecks, solves a murder, and gets the girl.

“Can we please talk about anything else?” I said. “It’s been nearly 20 years. You must have something else you want to talk about.”

So we caught up a bit. He told me what it was like living at home again. I talked about Asher and Hannah and the dog and the two cats. I showed him the pictures I’d shown my mother. But he was more interested in what it was like to be a writer so I told him the story of being on a panel with two other debut mystery authors: a Harvard-educated straight white guy who wrote a book about a straight white lawyer who walks around Brooklyn and Manhattan and runs into interesting people who sometimes share their names with real people and stumbles onto a mystery that’s mostly incidental to the story and a Harvard-educated Asian lesbian who wrote a book about an aimless Asian lesbian who rides her bike around Brooklyn and Manhattan and gets ensnared in a mystery that turns out to be mostly beside the point. “The thing is,” I said, “their books were amazing and they were both so accomplished, and only in their twenties. They had finished MFA programs. They had law degrees, both of them. I felt like a fraud. Actually, I felt worse than that.”

“I think it’s called impostor syndrome,” Patrick said. He sounded bored. “Oh, I meant to tell you, I invited Sally to join us. I didn’t think you’d mind.”

Sally Smith, I think she was Sally Krom now, was my first proper girlfriend. We dated the summer right before junior year. When the school year started Susan King, the prettiest girl at Buckskill Falls High, showed a brief and unexpected interest in me, so I dumped Sally immediately. Susan and I lasted all of a week. We talked on the phone for hours every night. That was the best of it, at least for me.

I hadn’t seen Sally since a couple of summers after graduation. We had drunken sex in the back seat of whatever old dilapidated car she was driving at the time. Sometimes I google Susan King but the right one never comes up. There was a TV news anchor with that name. I’ve looked at tons of pictures of her over the years. I can never seem to find my Susan King.

I motioned for the bartender to open another bottle. She looked amused.

Patrick lowered his voice. “Oh my God, don’t turn around but I think that’s Bob Gallagher.”

I pretended to itch my chin with my shoulder. There were three guys at a table behind us. They were all wearing MAGA hats. One looked a lot like Bob Gallagher, but then again, he was a pretty generic redneck. His nickname was Gigs. He stuffed me in a locker once. That was the extent of what I remembered about him. One of the other guys was my friend from earlier, the one with the chained-up pitbull. I looked away quickly and drank more wine.

Patrick was still whispering. “I heard he was at January 6.”

The bartender was uncorking another bottle. She refilled our glasses. “He brags about it constantly,” she said. “But who knows.”

“Maybe we should turn him in,” I said to both of them. She walked off to attend to another customer.

“That’s fucked up,” I said, “wearing those hats.”

“You see them all the time around here,” Patrick said. “The shock value wears off.”

I shook my head. “Not for me. It’s like seeing a confederate flag. Or a swastika. I saw a girl at the beach last year in a confederate flag bathing suit. Jesus Christ. I don’t know how you live here.”

Patrick looked at his phone. He didn’t seem to want to talk about it anymore.

Sally arrived. She didn’t look that much different other than in the way we all do. We had always made an odd couple, she was much taller and big all around–breasts, hips, the whole nine yards. Zaftig is the word, I guess. I was pretty small in high school. I’m still pretty small. A girlfriend once said to me, “Adam, you’re a small man.” It was part of a breakup speech. I lifted weights a lot right after college to try to get bigger, even though I knew that’s not what she had meant. Sally hugged me and whispered in my ear, “I think that’s Gigs.”

Wait, there’s one other thing I remember about Bob Gallagher: Sally had sex with him right after I broke up with her. Probably to get back at me.

Sally situated herself on a stool. She gave me an exaggerated shove that nearly knocked me off my stool. “I can’t believe you didn’t put me in the book. I lost my fucking virginity to you.”

The bartender came over with a glass for Sally. Now she looked even more amused.

Sally drank down the glass in one gulp and poured herself another. “Patrick’s in it,” she said. She motioned to Gigs at the table behind us. “Even he’s in it.”

“It’s fiction,” I said again. “And nobody fucking read it.”

We finished the bottle and ordered another. Was that the third or fourth? They both asked me how my mother was doing. I relayed some of the wackier things she had said. It wasn’t very nice of me to do but I was glad to get them talking about something other than my book. Which is strange because normally that’s all I ever want to talk about.

Sally again motioned toward Gigs and his friends. “My husband has one but I won’t let him wear it out of the house.”

“I can’t picture Ronny wearing one,” Patrick said. “He’s too classy for that.” They both laughed.

Maybe Ronny wasn’t classy. Maybe that was the joke. I knew he was, or at least had been, a prison guard at Eastern Correctional Facility. My mother taught English there. She loved her inmate students and loathed the guards. She didn’t have any nice things to say about Ronny Krom. So he probably wasn’t classy.

“He retired a couple of years ago,” Sally said. “That job really takes its toll.” She looked directly at me. “He really liked your mom. He said she was so smart and really great with the prisoners.”

So Ronny was a nice Republican prison guard and was thoughtful enough not to wear his MAGA hat in public. “Was he at January 6?” I knew I was drunk the second I said it.

Sally laughed. “Fuck you, Adam, of course not. Not every Republican is a member of the Proud Boys.”

“Yeah, most of them are wonderful,” I said with as much sarcasm as I could muster. When Sally didn’t respond, I continued. “They’re trying to fucking kill us,” I said. Oh yeah, I was way, way, way drunk. “They want more automatic weapons for more mass shootings, they want to outlaw abortion so women will die in childbirth, no masks or vaccines so more people will die of Covid or whatever the next pandemic is, make trans kids’ lives so miserable they kill themselves. Jesus Christ.”

The bartender smiled at me. I felt noble. I drank more wine. Sally laughed. Now I remembered that her laugh was one of the things I liked most about her. She was completely uninhibited. “You haven’t changed at all,” she said to me. It wasn’t a compliment. She leaned over and kissed me on the cheek. She was wearing a lot of perfume. Hannah doesn’t wear perfume.

Patrick stumbled down off his stool. He came over and hugged me. “I’m not happy about the book but I’m glad you texted. I missed you. But I’m not happy about the book.”

I thought I heard Gigs and the other MAGA guys snicker as Patrick left. I shot them a dirty look. They didn’t seem to notice.

The bartender refilled our glasses, killing the bottle.

“Ronny’s a good guy,” Sally said. “Everybody likes him and he likes everyone.”

I was beyond drunk but I didn’t say, unless you’re LGBTQ, an immigrant, Jewish, Muslim, Asian, Black, Hispanic, disabled. At least I don’t think I did.

“We just try not to talk about politics,” she said.

“I just don’t get it,” I said. “It’s not politics, it’s life. You either think Hispanic kids should be kept in cages or you don’t.”

“What about Hannah? Do you agree about everything?”

“We agree on nothing,” I said. “But we have the same politics. We both oppose fascism.”

Sally laughed. The MAGA guys grunted.

Our glasses were empty. Then I was outside in the parking lot with Sally. This time her car was a Honda Pilot.

“You ever fucked a bald chick?” she asked.

Huh?

“You remember I had alopecia, right?”

That’s right.

She pointed to her hair. “It’s a wig.” She opened the backseat and climbed in. “Come on,” she said. It was freezing in the car. Her wig looked so real. She pulled it off. Her head was pointier than I imagined it would be. We kissed and fumbled with each other’s clothes.

“Do you want me to put the wig back on?” I did but I didn’t say it. And that wasn’t the problem anyway.

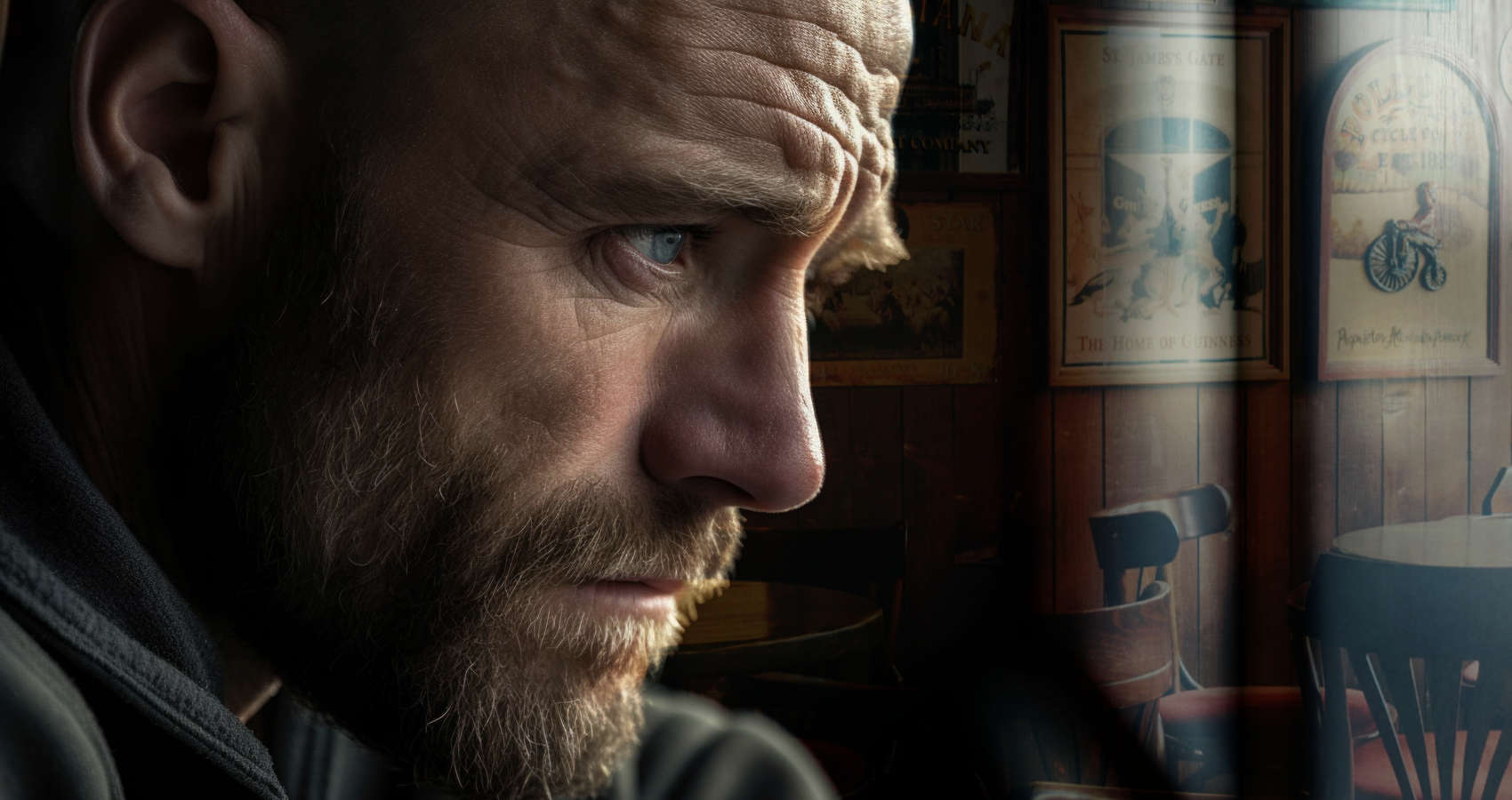

I muttered some apology or other and weaved my way out of the backseat and back into the bar. Gigs’ friends were gone. He was alone at the bar, laughing with the sexy ugly bartender. He had taken his MAGA hat off and placed it on the bar beside him like a good gentleman insurrectionist. Unlike Sally, he still had all his hair, but it was gray now and not as greasy as I remembered.

I hopped up on the stool next to him. “Two shots of your finest whiskey for me and my friend,” I said, trying to sound casual and a bit debonair. I was jealous of Gigs and the bartender.

She poured the shots. I drank mine down quickly, Gigs just stared at his. “Do I know you?” I couldn’t tell if he was putting me on. He had a good poker face. Pockmarked with a patchy beard, but it didn’t give away a thing.

“Adam Perlson. You stuffed me in a locker once.”

Gigs smiled. He seemed glad I remembered and glad to be reminded. “So you’re some kind of writer now, huh? Ever written anything I would’ve read?”

“I doubt it,” I said.

“Don’t think us rednecks read, huh? Only you bubble people, right?”

“I’m sure you read,” I said. “I bet you devoured The Turner Diaries.”

“Funny,” he said. “You know what books I like.” It sounded rehearsed, like he’d been planning this bit, hoping I’d take the bait. And, of course, I had. “Those killing books by Bill O’Riley. Killing Kennedy, Killing Lincoln, Killing Reagan. Those are fucking great. Know what my favorite is?” He paused for dramatic effect. “Killing the Jews.”

I remember another thing about Bob Gallagher. He used to throw pennies at me and the only other Jewish kid at our school. I think his name was Michael Warshaw. He didn’t have any friends. My mother liked him because he read Proust. At 14. That was about the quickest way to my mother’s heart. I haven’t checked but if I had to lay odds, I’d bet Michael Warshaw committed suicide. I don’t want it to be true, I’m just saying it wouldn’t surprise me.

Gigs slapped me on the back with a meaty paw. “I’m just fuckin’ with you Adam.”

He was and he wasn’t.

“Were you really at January 6?”

Gigs stopped smiling. Even filled with alcohol, I was a little afraid.

“Fuck yeah. And I can’t wait to go back.”

I desperately wanted to drink his shot.

“We won,” he said. “I’m going back for the victory celebration. It all starts tomorrow, that’s when we lay the groundwork. Then in two years he’ll be rightfully put back in the White House.” He smiled at the thought. “And if you thought last time was something, well, just you wait.”

“Well then,” I said. I pointed at the shot glass in front of him. “Aren’t you gonna drink it?”

But Gigs wouldn’t give me the satisfaction. He got up to leave without a second look at me. But when he got to the door he turned towards me and puffed out his chest. “It’s our time now,” he said. He put his red hat on, and that, combined with his shaggy gray hair made him look like a dystopian Santa from a nightmare holiday TV special–It’s a Very Trumpy Christmas. He made a gun out of his thumb and forefinger and pointed it at me. Then he was gone.

I grabbed the shot he wouldn’t drink and downed it. My hand was shaking. The bartender brought me a glass of wine. “On the house.”

I drank half of it. “Did you hear him?” I said. “That’s fucked up.”

She cracked open a bottle of beer for herself. “He’s harmless,” she said. “And he’s a good tipper.”

“Yeah,” I said, “so were the guards at Auschwitz.”

She raised an eyebrow. I’m also a sucker for that. “You’re not on Twitter, are you?”

“The question,” I said, “is why are you? Why is anyone? I don’t want to spend my remaining days fighting off an incursion of Russian bots.”

“That’s it,” she said. “It’s the way you talk. I knew you weren’t on it when you gave that speech about Republicans wanting to kill us. You could have just tweeted it.” She added, “And I don’t think he was really there, at the capitol.”

“I’m not sure that’s the point.”

She drank from the beer bottle and her tank top rose up ever so slightly. “Then what is?”

I shook my head. I was tired of trying to be profound and just coming off as pompous. And I was out of material. I’d just have to wing it from here on out. I pointed at the colorful sleeve of tattoos that covered her left arm. “My daughter would love that.”

“I thought you only had one kid.”

“I do. Max. She’s a junior in college. She’d think your sleeve was cool. She’s always asking us if she can get a tattoo.”

I finished the wine and fumbled with the cash in my wallet before laying it on the bar. I wanted to tip better than Gigs. A mega-tip beats a MAGA-tip.

The bartender turned off all the lights except the one directly over the bar. I thought it was romantic. It must have been written in bold letters all over my face.

“You know this won’t end the way you would write it?” she said. “We’re not gonna sleep together.”

“I would have written that,” I said. “I definitely would have written that.”

I was halfway out the door when she said: “How come you keep saying no one read your book? How do you know?”

“Because it was never published,” I said. “I couldn’t even get a fucking agent.”

***

My mother finished her oatmeal. “Did you feed Muldoon? Did you clean her litter?”

Behind his giant sunglasses my father was silent. He was furious at me for leaving.

“I saw Patrick and Sally last night,” I said. “You know, from high school? Sally’s husband knew you, mom, at the prison.”

My mother smiled. “I was very popular,” she said. “But not with the guards. They were so stupid.”

“Well, he liked you.”

“I need to start dinner.”

It was 9:06.

“I have to go,” I said. “I’m sorry.”

At the front door, with my backpack slung over my shoulder, I hugged my tiny little mother goodbye. “I love you, mom.”

“I love you, Simon.”

I called Lisa from the road. “I won’t be home late. Do you want to wait for me and we can vote together?”

She said she already voted. Work was crazy and she had to go. She said Rufus had missed me, that he knew it was me on the phone and that he was wagging his little tail enthusiastically. I smiled. Then I thought of that poor pitbull all chained up. It reminded me of Gigs’ ominous threat. It was his time now. Maybe after the dog ripped the throat out of that asshole who chained him up he would take care of Gigs. Now that would be a happy ending.

On that panel with the two young, impossibly accomplished authors, only one person asked me a question. She wanted to know what it was like to have my first book published in my mid-50s. I made some trite joke about getting older, probably something about having to get up a lot to pee. Neither of the other two panelists bothered to even give me a courtesy laugh. It was like I wasn’t there at all.

- One Night in Chagrin - August 15, 2024

- The Neverending Adventures of Eleanor Dobbins - May 12, 2024

- Persistent Memories - December 31, 2023