The Scientist’s Daughter

written by: L.C. Schäfer

I was born in the middle of winter, and the birth was difficult. My father sent for a midwife, but she couldn’t get to us in time to help my mother. My mother died. My father began to obsess over the specialist knowledge he lacked which could have saved her.

One of my earliest memories as a child is my father interviewing women wise in the ways of childbearing, and writing down everything they told him. We used to live in quite a nice house back then, although I was too small to concern myself with things like that. It was a spacious house in the quiet countryside. He paid these women handsomely to travel to us, and sit with him for hours sharing their knowledge. Since I had no mother of my own, Father hired a wet-nurse. Once she and I were provided for, he spent every penny he had to uncover the secrets women guard with their bodies.

When I stopped needing a mother’s milk, he kept my nurse on as a nanny, leaving him free to pursue his studies. He eventually replaced her with a governess to teach me my letters. And all the while, he kept learning as much as he could, about the inner workings of the human female, and the mysterious passage out of it.

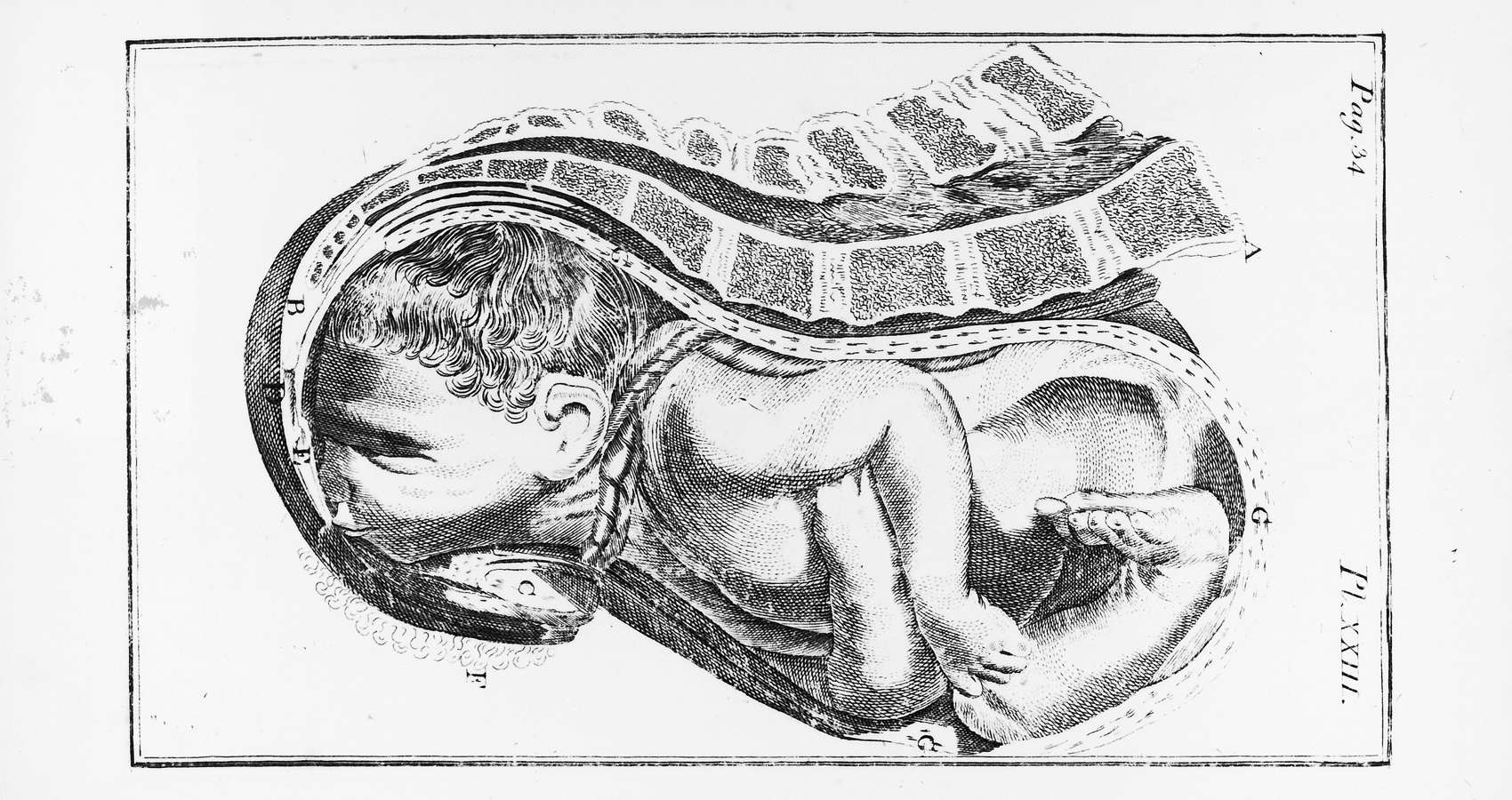

My father kept meticulous journals, with every detail he could glean. No tidbit was too small, nor too personal or gruesome. He drew elaborate diagrams.

At last, he had reached the limit of what he could learn from theory. He wanted to put it into practise. I could not grasp this fully at the time, but this was forbidden knowledge for a man. No decent woman would tolerate a man near her when it was her time. His solution: he started tending to the ones society decided were indecent. The ones who had nowhere else to turn.

Girls and young women started coming to stay with us. Sometimes for a few days, sometimes for a few weeks. “Girls in trouble”, he called them. They arrived with big bellies, and left with small ones. Strange cries came from the guest rooms. I was not allowed to enter. All I knew was that they needed help, and Father was doing his best to give it. Sometimes they took their baby with them. Other times Father took the baby to the orphanage.

I remember one girl. Her name was Rosalie. She had light brown hair and dimples. Her clothes looked tattered, and her eyes looked afraid. She was older than me. I was seven and she was maybe fourteen. She seemed very grown up to me at the time, but now I look back and remember a child, tasked with something no child should endure. I liked her. I fancied she might stay with us always. I was lonely without other people near my own age to play with. We lived way out in the countryside, no neighbours’ children to keep me company, and no siblings to squabble with.

I remember Rosalie arriving, alone with a small suitcase, but I don’t remember her leaving.

Her labour was long and difficult. I knew it, even as young as I was. She stayed shut in the room, her periodic cries punctuating the night, then the day, then the night, then the day…

Finally, the cries stopped. The room was deathly quiet. I should have been asleep, but I had taken a shine to Rosalie, and I wanted to go and see her and peek at her baby. When I crept out onto the landing, I caught an odd sight: two gruff-looking and dirty men talking with my father downstairs. I crouched by the bannister and listened hard, but they were speaking too softly and I couldn’t hear what they said. I watched money change hands. One picked up a bag and slung it on his back, and then between them, they picked up an odd long wrapped bundle off the floor and carried it out of the house.

Father rubbed a hand across his face and turned to his cabinet. His steps were heavy. He poured something golden into a shiny glass and threw his head back. When he turned towards the staircase, I shrank back into the shadows and scurried into the room I shared with my governess.

The next morning, I went to visit Rosalie. I wanted to ask her if I could bring her breakfast. I planned to make her to like it so much at our house that she wanted to stay. Father worked hard, and needed a helper. She could do it, when the baby wasn’t drinking milk. They would be my big sister and my baby brother. Maybe, when she was completely grown up he could marry her and I would know what it was like to have a mother. I pushed the door open, wearing my best smile, but the bed had been stripped and the crib was empty.

“Where is Rosalie?” I asked.

“She’s gone, pet,” he answered.

“But she’s forgotten her suitcase.”

***

I don’t know if that was the first time it happened, but it wasn’t the last. Every so often, another girl would come to stay with us for a while, and every so often, that girl would just… disappear. When that happened, those unpleasant men returned to take away the grisly parcels. I am not sure if they were the same men, but they had a similar manner. I didn’t like them. What had they done with Rosalie?

Father grew impatient with the slow trickle of patients he had to practise his craft on. We moved from that lovely big house in the countryside, to a cramped little space nearer to the castle. It was muddy and bustling and loud. I thought I had been lonely before, but this was worse. It is always worse to be lonely when surrounded by people. Maybe the more people there are, the lonelier you can feel.

I hated it. I missed the big house, the peaceful countryside and fresh air. I missed my governess, but Father said I didn’t need one anymore. He hired a tutor to come and give me lessons twice a week instead. He put a pallet next to his own bed for me to sleep on, and he had a steady stream of girls to tend to. He set me to work copying out his journals, because he said I had a fine hand for my age. Through the thin walls, I heard the groans and primal shrieks from the troubled young women, while I drew carefully annotated pictures of their insides.

The night-time visits from those strange men were much more frequent. Sometimes they didn’t take away a bundle (containing my most recent big sister) – sometimes they brought one. It would be taken into the cellar, which Father always kept locked. But before he accepted it, he always unwrapped some of the shroud to see what they had brought him. It was always women, or girls. Sometimes they were big-bellied. He paid the most for those. After one of those grotesque parcels, food would be scarce for a little while. Meals would be smaller, and Father would sometimes skip dinner completely. I look back and suspect that some of those bodies were far too fresh.

***

I might have been eleven or twelve when the soldiers came and arrested him. He sent me to my room and told me to stay quiet. I did as I was told. I didn’t see the soldiers drag him away. I couldn’t run after him crying or shouting. He was here, and then he was gone.

***

The next few days are a blur. My tutor visited, and so did a neighbour. They made sure I had something to eat, but I wouldn’t leave with them. I was frightened someone would put me in an orphanage and Father wouldn’t be able to find me. Or that someone would move into the house once it was empty, and then neither of us would have a home. A treacherous thought danced across my mind: that he might not come home. Ever. I pushed it away. I couldn’t think of that.

It was night time, and I was asleep in Father’s bed when he returned. He leaned over me in the moonlight and kissed my forehead and told me everything was going to be OK. He looked gaunt and dirty, but he was smiling. The King was very angry with him, he said, but was going to give him a chance. He had to do a job for him, and then the King would forgive him. He was going to come home, and be an ordinary doctor, not a scientist anymore, and everything would be alright again.

He packed his bag, the weird tools and wicked looking knives glinting sharp and clean, and he left again.

What comes next is rather horrible, I am afraid. I am not completely convinced it is true. I have sometimes wondered whether Father went a bit mad. I want to suggest, that if you are a lady with a big belly, you stop reading and don’t come back. Go and make yourself a cup of tea instead.

Father was gone for several days. I wasn’t worried anymore. He had promised he would come back, and things would get better. He had many faults, of course, but he had never actually lied to me. I had no reason not to trust him.

When he came home again, my heart broke. He could not speak, and he could not write. His hands were broken and someone had taken out his tongue.

We cried together. I did my best to bandage his hands, but I was shaking so hard I wasn’t very good at it. He did his best, with gestures and grunts, to instruct me on how to do it better. We started, right then and there, to devise our own way to communicate.

I made him something to eat. I had to take care of him now.

***

Over time, our language developed so that we could hold a simple conversation, and I could discover some of what had happened at the castle. With gestures, and questions, head shakes, nods, the odd word or symbol scratched painfully on a piece of paper – little by little it all started coming together.

I thought I already knew the worst of it – that someone had so grievously injured him in return for the service he gave the King that I would never hear his voice again, and he would never use a pen. Not the way he used to, anyway. But there was more, almost as bad, or maybe worse. I really do recommend that cup of tea.

The King wanted him to attend a birth. That part was not unusual. Father had done that many times before, although not at the request of a monarch. The King was not married anymore, since his second wife had died when she miscarried his son. I imagine there must have been a young woman he’d “got into trouble”. He had hired Father to help and to be as discreet as possible, to protect the royal reputation.

It was a hard labour. The hardest, I think, Father had ever seen. The woman was too little, or the baby too big. Perhaps both. The woman swam in a pool and wouldn’t get out. The water was cold and dirty, and salty. And here is the part where I think he might be mad: he says she had a tail.

“A tail, Father? Is that what you mean? A tail?”

He nodded vigorously, and pulled the parchment towards him, drawing a simple fish shape with two curved lines and tapping it urgently.

“A fish tail?”

He took hold of my hand for emphasis, though that must have pained him, and nodded all the harder.

He picked up the knife I had been using to eat my dinner (thankfully I had finished with that) and waggled the blade at me. Then he put the knife back on the table, leaned forward and drew a line across my lower belly with his forefinger.

My mouth made a round “O” of perfect horror.

“Did she live?” I whispered.

He shook his head.

***

Her baby lived though. He is at the castle, and he has red hair like his mother. The King claims he was a foundling. The servants call him Fynn. The rumour goes that he sings beautifully, and his voice echoes sadly across the ocean.

- The Scientist’s Daughter - August 22, 2023