Down On One Knee

written by: Kim John Farleigh

@KimFarleigh

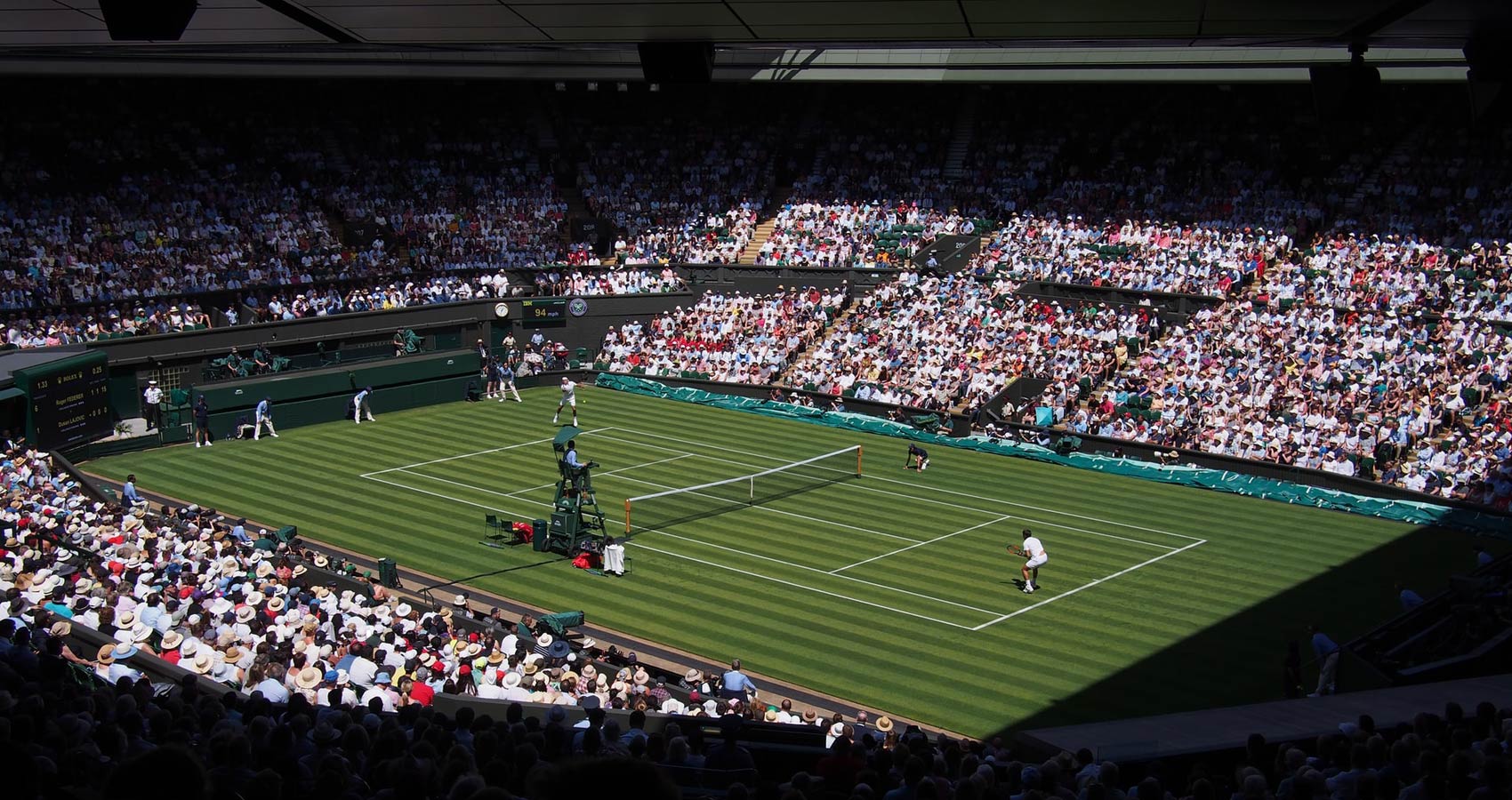

A long queue fed the centre court. The queuers had already had a three-hour wait outside the complex just to get in, roaring crowds on other courts provoking: Should I go to another court? Will this waiting to watch on the centre court be worth it?

People sat when the queue was stationary, leaping up when the queue moved, rapacity burning under civilised facades, collective mistrust until the next stop reasserted previous positions, other-court applause beckoning the queuers like Sirens.

People left the centre court, saying: “Hell. Hot. Awful. Too crowded.” Perfect. I wanted torment so I could watch tennis.

The queue leapt up again, sharp action with mistrust, docility again as positions got reasserted.

My smug superiority rose when someone said: “I can’t take this. I’m going.”

The quitter puffed his cheeks out before exhaling, defeated by unrewarding uncertainty.

He, I smirked to myself, expected a pick nick.

At a curve in the tunnel that led to stairs that rose into the centre court the queue broadened, people moving to the right where getting access to the court was easier, pushing in blatant; a Scottish, female security officer, with powerful arms and livid, green eyes, yelled: “Get back into the queue,” as people drifted to the right, the centre court’s standing-room area now visible, the enthralled, packed-in crowd above us resembling locusts gorging on action carcasses, silences broken by applauding, spectators breaking out of watching-wall flesh to sit on the stairs, the security only letting a few people do this at a time, one person’s lolling head finishing up between her legs, her arms wrapped around her raised knees, unprepared people spending hours in the sun without drinking.

The seated woman rose and forced her way back into upright, massed, absorbed meat, disappointment’s horn groaning through my frozen cavern of hanging, mental ice. I had been hoping she would leave. I wanted my place at the banquet of glamorous irrelevance.

A middle-aged woman sat on the stairs, somebody saying: “What’s she doing there?”

Age, not location, had inspired this, the woman’s dress reaching her calves, an imitation pearl necklace on her chest, her hat, like an anachronistic bathing cap, pasted to her head by a white, elastic strap, her fragile paleness foreign amid bronzed youth; the woman, trying to rise, gripped an iron rail that lined the stairs. A security officer asked her if she was all right. Her head fell as her reassuring right hand rose, the security officer not inquiring further–the match had restarted, the security man returning to his viewing spot; the woman swayed as if drugged, fighting to stay upright, the arms-folded security man fascinated by a modern substitute for our prehistoric battles, the collapsing woman’s legs spreading apart, her head reaching concrete, people seeing up into her crutch, her thigh cellulite like white custard, her black stockings making a violent contrast with her bone-hued obesity, people giggling, the swaying woman struggling to beat an imaginary count.

The security officer jolted on seeing the woman; he charged down the stairs, responsibility freeing him from combat’s magnetism. Fighting his way through the queue, he asked people to move, everyone reluctant to give up territory, only minuscule steps made, each queuer hoping the man would harass others, people avoiding eye contact, each queuer a detached unit of mistrusting selfishness wanting to win space to defeat others, off-court competition as vibrant as it was upon clipped grass, the Scot screaming: “Get over!” while pushing people aside, the people believing they had a lot to lose, glamorous victory revered in competitive societies, the dehydrated lady’s head flopping as people chuckled.

Two men at the top of the queue couldn’t stop smiling. Their faces contorted into amused disgust. The view up between those legs yielded a humour as ebony as the woman’s stockings. The men, wearing Ralph Lauren shirts and blue shorts, had black, wavy hair and olive complexions. Sunglasses adorned their heads. One had a gold chain around his neck.

One said: “Ten bucks if you mount her.”

Their hands covered their spreading mouths, eyes like polished pearls.

The security officer had run off to get a stretcher, meritorious action pulling him away from a contest between rich unknowns.

“Nearly down for the count,” one of the men said, the woman averting fainting by hauling herself up. “Will the referee stop this or not?”

Two smiling, young women, wearing white clothes and pink shoes, one with permed hair, had also placed their hands over their mouths as other people averted their gazes as the fallen woman, as detached from her surroundings as the crowd was from her, fought unconsciousness, maybe death, the packed, gripped crowd behind her watching balls flying over a net, mutual facial expressions turning the crowd into indistinct units of the same species, their interest in competition exceeding their sensitivity towards suffering, the permed-haired girl, laughing the loudest, staring, with gleeful eyes, at the fallen.

An elderly lady, talking to an American, said: “Poor woman. Oh, poor woman!”

People became quieter–the irate Scot could deny entry–the elderly woman saying: “Oh, dear, that poor lady. My God, she looks terrible!”

Muffled laughter emerged from the permed-haired woman, the Scot yelling: “Get over!”

“I can’t,” Permed-Head said, “I’m stuck. Move everyone back.”

The Scot moved everyone back, and slowly, after much churlish harassment, the queue lengthened, creating space; but Permed Head didn’t budge, afraid she would lose the place that she had stolen to get.

“Look, you,” the Scot said, “you wanted the queue to go back and now you won’t move. Get over!”

The Scot’s Glaswegian accent added venom to her venomous remarks, Permed Head exhaling as if victimised by unjustified malignity, not understanding why she had to endure this suffering, that her laughter had magnified Glaswegian fury, the two men at the top of the queue observing the ground with radiant eyes as the woman collapsed again, the crowd’s cheering ironic, for a player had just taken a set, victory as the woman had fallen, her legs splayed, the applauding people unaware of the distress behind them, the Permed Head’s previously gleeful eyes now full of harassed astonishment for the unbelievable mistreatment she was receiving from the Scot who glared at her like a wild feline, the elderly lady saying: “Is anyone going to do anything about this?”

People chortled as the woman’s lower-abdomen region got exposed. I thought: What if she was my mother?

The American, bursting by, deliberately bumped Permed Head as she giggled, this giving me a flash of pleasure, her hand shooting away from her mouth in shock, her ringlets of curly follicles shaking like her shaken-up dismay, her sniggering replaced by surprise–more inexplicable harassment!–the American, picking the fallen woman up, pulling her dress down over her legs, letting her head rest on his shoulder, the woman wincing like a punctured lung.

“Thank you,” she garbled. “I’m okay.”

“Relax,” the American said. “A stretcher will be here soon.”

She tried to show she could help herself, but her body was limp, the skin bluish under her eyes, as if she had a disease, her undefeated dignity enhanced by the grave faces of those who had delighted in her collapse, disquieting silence echoing through the tunnel’s cavern.

The American carried the woman into the shade where the victim’s proximity, her white face partly purple, arrowed repugnance through the humid air, people staring in unnatural directions, Permed Head taking a glimpse; then, distressed at having to face ugliness and not glamour–more harassment!–looked away without muffling her groan.

People now found concrete aesthetically pleasing, grey flatness better than confronting moral inadequacies.

“I hope you lot find this funny now!” the Scot screamed.

Faces mimicked the grim concrete, the thing most faces were now staring at, nobody reacting for fear of being denied access.

The stretcher arrived. The American, going down on one knee, lowered the woman onto the stretcher’s orange bed whose sunset hue reflected a peaceful end.

“Well done,” the elderly woman said, patting him on the back.

“Well done to you, too,” I said, the rest silent, except the packed, locust-like crowd above that was feeding on combat.

And I still couldn’t wait to join them, the future too distant to be significant. People aren’t prepared for death. If they were, we would love each other in mutual acknowledgment of a shared fate instead of living in a stand-off against inevitability that glamorises the irrelevancies created by our love of survival through winning.

I was only slightly different from the majority because I accepted my shallowness.

The next day’s headlines celebrated what ended up being a magnificent five-set encounter. Millions no doubt talked about it. I certainly did.

The woman’s death filled one paragraph on page twenty-four of The Times.

THE END

- A Deadly Dream - February 25, 2023

- Spotlight On Writers – Kim John Farleigh - November 5, 2022

- Perspective - August 2, 2022