Writing on Wood

written by: Lauren Roman

The branches snapped underneath my footsteps. Each break reminded me of a broken bone. An imperfection. Crunch.

Numbers clattered inside my memory. Multiplication, dividends, equations. Repetition, repetition.

2×2 is 4. 5×7 is 35. If I could count the stars, I would. And, sometimes at night, after a long day of work, I believed I could.

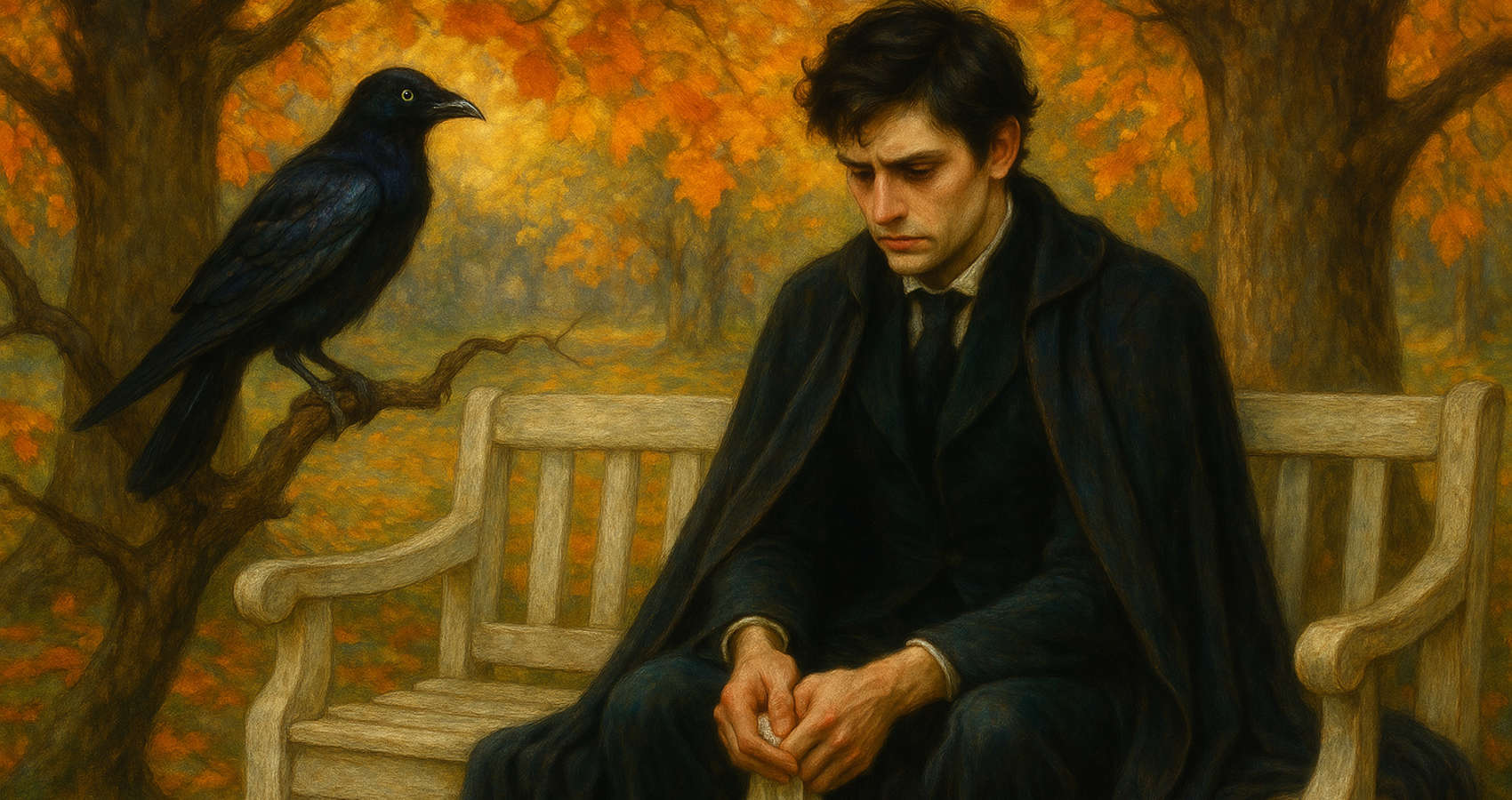

The dead wood groaned after a brief kiss from the October wind. It ruffled my dark, feathered hair, and I pulled my cloak closer around my body.

“Get it right. Make sure it’s perfect,” my father once commanded over my shoulder. I never realized how alive I felt when I imitated death. There I would be, still as a statue, immovable as the grave, as I hung over my childhood desk. I remembered it was mahogany, much like the twisted bark of the small cluster of dead branches lying at my feet in the park. My fingers would move, but my heart wouldn’t notice it. I was a robot, incapable of making mistakes.

My throat worked. Until–I furrowed my eyebrows. A small raven pulled me out of my reverie. Its left eye was green. Imperfect. My skin grew pale. I lowered my head to the ground and skipped over a fissure in the stone tile of the walkway. I’d never stepped on one crack my entire life.

“Such a good student. You should be proud,” my third-grade math teacher had said. “What Aaron needs is a push. And who knows? He might become the greatest mathematician this world has ever known.”

My fingers worked at my sides. My father never left me alone since then. Even now, in the middle of Briar Park, I could feel him looking over my shoulder. I turned to make sure, just in case. But, the only person near me was an older man with skin as wrinkled as an elephant’s and a cloak punctured with holes. His gnarled hands were filled with garbage as he reached deep into one of the tin cans.

I wrinkled my nose at the smell. Instinctually, I pulled a handkerchief out of my pocket and covered my face with it to keep out the particles that hovered in the air. It’s a scientific fact. Everyone knows it. Then I carefully dabbed my face to rid myself of whatever germs the man must’ve shared with me.

“There can be no mistakes,” my father would say. I would nod my small little head and tell myself my own personal mantra. I am well-practiced like an athlete in training. I am a human instrument, and I make my parents proud.

An isolated white wooden bench lay tucked in between two trees brimming alive with a combined shade of orange and yellow. The leaves shimmered and rustled over my head.

“Never take this for granted. The opportunity you have, now,” my father had said. I still remembered the white pamphlet he had handed to me, however, the name of the university blended behind a slab of gray stone. The words scrawled over it were more important to me now than what had been written on that flimsy piece of paper then.

I shuddered from the cold and used my other hand to quickly wipe away the dust from the seat. However, after I lowered myself to sit, I felt something bulbous underneath my bottom. I quickly jumped up and cursed under my breath. Something small skittered away, and by the time it reached the edge, it sprouted wings and flew.

Something lodged inside my throat, making it difficult to breathe. I didn’t want to sit anymore. I wouldn’t. And I wasn’t going to, until a small man appeared out of my peripheral vision. I groaned inwardly. It couldn’t be. But, no, there he was. Right on time, as usual. If it weren’t for the pride I had in his accuracy, I would’ve left a long time ago.

“Hullo, Aaron. Nice day today, isn’t it?” I fought the urge to roll my eyes.

“It would be. If we were in the office. Where we normally meet,” I grumbled.

“You know why we can’t do that. Having a change of scenery is good for you. And beneficial for us,” he reassured me. Us. Ray liked to use that word often. As if he were in the middle of this with me, able to read my mind and suffer for it. I grabbed my arm and coaxed a wrinkle out of my sleeve.

“I saw a raven before you came. You know what that means, Ray,” I said.

Ray wrinkled his white eyebrows. He was lucky to have hair at his age. I hoped I did, but my father didn’t. So, according to the probability of genetics, there was no hope for me. Ray was also a squat man and a couple of inches shorter than me. His monocles slipped until they reached the end of his long, pointed nose. He adjusted them quickly and brushed the frame with his stubby fingers.

“No, I don’t believe I do.”

“In Sweden, they are symbolic of the ghosts of people who have passed. Lost souls who never gave their lives to Christ.”

“Ah, I see.”

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence, you know. It’s been a year.”

Ray studied me carefully. He didn’t have the look of a doctor. The way he observed me was more like a well-mannered grandfather attuned with his grandson’s emotions. He always carried himself that way. And it made me feel small and insignificant. I lifted my posture, horrified to discover it had sagged. With newfound confidence, I spoke again, careful to hide the building tremor in my voice.

“But I know where he is. He never deviated. He lived a perfect life.”

Ray adjusted himself in his seat. The clamor of people reached our ears as a dog sprinted past us. His sleek orange coat matched the colors of the leaves and the dull hue of the day. I hadn’t noticed at first, but he caught a stray white ball that had been flung into the air and obediently rushed back to his owners. Close by, a boy with a mitten hung his head, defeated.

“Being perfect isn’t always a good thing, you know. Don’t get me wrong, it’s great you have reverence for who your father was. Every child should have that to hold on to at the end of their parent’s life.”

I gathered up my collar at my neck in bunches and braced myself for the finishing statement. It was always abrupt and as significant a blow as a swift punch to the gut. Instead, Ray reached down to cradle a round stone in his hands. The smooth surface appeared soft in his grip. He fumbled with it, and his eyes became distant. Lost to the rolling of the small hills of the park. They curved like rounded backs and were filled with families and children.

“But, tell me, Aaron. If your father were still alive, what would you say to him?”

I blinked at him incredulously. “Well, that I love him. Anyone would say that.”

“I’m not asking what anyone would say. I’m asking, what would you say? I want to know your personal thoughts. We’ve had several sessions now.”

“I’m off my medication,” I interjected. “Doctors have told me I’m a new man.”

“And that’s good…”

“So, objectively, I have improved much since our first meeting, together.”

Ray waved this off and sighed. His shoulders collapsed, and he rubbed his face. “Yes, but there’s still much more to be done. You’ve yet to open up to me about your feelings, for one.”

I clung to my clothes and curled my feet inside my narrow, black shoes. The dog passed by again. This time, he outran the small child with the glove lodged in his hand. The boy squinted into the daylight and searched the sky. However, the ball passed him and landed close to my head. I pulled out of the way and was disgusted to discover a cake of mud had exploded onto my perfectly pressed suit.

“Hey mister, could you hand me my ball, please?” I ignored the little boy. Instead, I stared at his canine companion who did the work for me. The mutt snatched the object as fluidly as one of the seagulls on the harbor with their fish. After giving me a sidelong look, the dog left, and I heard the child’s voice again. Except this time, it wasn’t the boy’s but my own.

“I just wanted to play, daddy.”

I stood up and froze. Ray had done the same. I hadn’t realized he had. He carefully outstretched his hands as if he were ready to catch me. “Aaron, are you alright?” he asked carefully. I glared at him.

“Well,” I stammered. “Perhaps it would’ve been easier to open up if you had brought me to the office, like we originally planned. Instead, I have to watch that child miss every catch they’re throwing at him. It’s pathetic. I mean, look, the dog has to intervene because of how many times he’s missed it!”

I marched away, oblivious of the fact that I captured the mother and father’s attention. As I put some distance between me and them, I mumbled under my breath. “I can tell you this. He will never grow up to be a successful baseball star with an arm like that. That’s for sure.”

My heart hammered inside my chest. The wind whistled in my ears and drowned out the noise around me as if I had plummeted underwater to another time and place.

“You’ll never grow up to be a great mathematician, playing in the mud like that,” my father had said.

I counted my steps, but there were too many to count. Ray chased after me like my own personal shadow. Shoulders bumped into my own, and I squirmed after every hit. However, I continued on, as if I were on autopilot. My hands trembled in my pockets, and my fingers played around my handkerchief as if they weren’t sure which to clean first. At this point, my body was filthy.

Ray grabbed my cloak. “Aaron, stop!”

I turned abruptly and shrugged away from his touch as if I had encountered flame. While I glared at my counselor’s hands, I noticed a pile of dead branches that fell from their parent tree. They gathered at the foot of a small pothole, and my mind was cast to a ditch filled halfway with rainwater.

My body had stirred inside the small ravine as I turned to face my father. His wet hair clung to his forehead, but my attention shifted to his gnarled hands. They clung to his belt and unfastened it around his hip.

“You’re going to learn, boy. Perfection doesn’t come without sacrifice or risk. You have to pay a price. We all do. But whether you learn your lesson or not will have dramatic repercussions for this world. So, my role as a parent is to make sure you understand,” the buckle had flashed at me. “Everyone strives for perfection. But, for you, there can be no mistakes. You cannot make any. Is that clear?”

I nodded my head and felt the weight of an entire world collapse onto my shoulders. My father just looked at me. He never blinked that day, and that scared me all the more. “Turn around,” he had said. “This will be seven hits times seven rounds, son. How many is that?”

“Forty-nine,” I had responded. If I counted the seconds and my father timed it correctly, I wouldn’t have stood there for longer than a minute. So, it would take less than sixty seconds for the pain to pass and the moment to be over. I remember I shut my eyes and started doing what I do best. Counting, calculating.

Tears spilled down my cheeks in uneven outbursts. When I opened my eyes, I was back in the park. I had twisted too fast away from Ray and, to my own horror, the tips of my toes crossed one of the cracks in the path.

A low ringing sounded in my ears. I felt like deadweight. Or, as if the world around me had passed. Something ate inside and left my body hollow. I tried to count, but the numbers didn’t come. Everything was silent. I landed on the ground and sat there, as immobile as a rock.

Ray stayed away. For a moment, he blended into the crowd of bystanders who gathered close to where I fell. They waited patiently for a breath or any sign of movement to signal I was alright. But, to me, they were invisible.

For the first time in my life, something popped inside my head. But it wasn’t a calculation. It was a gathering of words. They stumbled and rolled over each other until they were placed in coherent sentences. I could see shadows of formulas behind them, burning away from the spotlight.

How do you feel? Ray had asked. I gritted my teeth and shuddered. The world around me turned dark when I closed my eyes. I felt cold. Dry and brittle as a bone. Dead. The shame of breaking my lifelong streak of never stepping on fissures in the ground overwhelmed me. But, more than that, I felt the guilt of being imperfect.

I raised myself up without thinking. Murmurs from the crowd reached me, but I ignored them. Instead, I strayed from the path and snatched the sharpest branch I could find. With my new instrument in hand, I marched over to one of the trees and carved sentences into the bark. When I wasn’t satisfied, I scratched what I wrote out and began again, and again, and again.

All of a sudden, time didn’t matter. There was a low, steady buzz that ringed in my ear as if a bee whizzed past my side. Before I knew it, the world returned gradually. First, I could hear the low hum of car engines, then the sound of children laughing, and the melodic stringing of instruments playing.

By the time I turned around, I hung my head and felt the stickiness of the earth attach itself to my skin. When I wiped my face, I saw more mud wrap over my palm and wedge itself underneath my nail beds. Ray just stood there with a wide grin on his face. Tears brimmed his eyes and he clapped his hands together, delighted. “Attaboy, Aaron. You move me.”

I widened my eyes, suddenly aware of myself. “What have I done? I’ve finally snapped. Those people,” I pointed to the crowd that slowly began to disappear. “They all think I’m insane, and if they told me that to my face, they wouldn’t be wrong. I’m crazy.”

“Sometimes doing the right thing and making the first step toward healing is going to feel like a miscalculation. But that doesn’t mean it isn’t good for you. Good for your own little world and all the people in it.”

My teeth chattered inside my mouth. From anger or sadness, I wasn’t sure. But my jaw was sore from all of the tension I felt build inside me.

“What did you write?” Ray asked. I gaped at him. At first, I didn’t think I could remember. It all came out so fast. But, as if I had spent as much time memorizing it as I did my math problems, I spoke.

“You hurt me. By pushing me, you pushed my mind to the point that nothing makes sense except numbers. I see probabilities instead of people. And, now, I feel more like a machine than a man. Checking and re-checking, making sure I do not slip and being absolutely certain I don’t make mistakes. And now I have to live with that for the rest of my life. An outsider to myself and others.”

“But you don’t have to live like that, Aaron. The writing is not on the wall, as you might believe it is. On the contrary, it is on the wood,” he gestured toward the tree I marred with my writing and smiled. “Written by your own hand.”

As he walked away, I looked over my shoulder and observed my footprints on the ground. I twitched and winced from the gravel-like texture that contaminated my skin. Instinctually, I reached for my handkerchief to wipe away the dirt, but I paused. My fingers clenched around the fabric, yet my mind drifted elsewhere.

What I wrote stared at me, like a long-lost friend. I couldn’t logically get it to make sense. Whether it was a high probability that a human could be compelled to write their feelings on wood after years of compartmentalizing their emotions. Or whether they too, if pushed enough, would be able to do something so erratic or spontaneous. Probably, I decided. Perhaps it was written in a book somewhere, but that didn’t matter.

Slowly, my fingers unclenched themselves from the handkerchief in my pocket, and I hurried after my counselor. When we walked, I noticed how warm the sun felt on my skin and felt the breeze wipe the sweat from my brow. Everything was so crisp. Fall was coming, and the colors danced in front of me in hues I hadn’t noticed before. And like a toddler learning how to walk, words formed in my head to describe them all.

- Writing on Wood - April 13, 2025

- The Nativity Scene - December 14, 2022