The Unfaithful Earl

written by: Hemmingplay

@hemmingplay

With one exception, no one in the pub that night had heard the story of the dead earl with the spear in his guts…. At least, not since they were children.

It was a quiet evening. Truth be told, it was like most evenings in the little village.

This night was running down in the same way. Nothing moved outside, or inside, except for calls for refills by the few villagers who remained.

But just before closing time, Robert Mordrum, a local farmer, burst into the low-beamed gathering place just before closing, white-faced and speechless.

The night seemed to come in with him in a dark swirl of leaves, cold and trouble. He headed straight for the bar.

The landlord pulled a pint and put it on the ancient bar without asking. He’d been serving drinks here for 40 years, and knew a man in need when he saw one.

Af few of the others drew closer, hoping for something to enliven the dreariness.

Mordrum, his boots caked with mud and manure from the barnyard, took a long draught on the mug, then another. It was gone in two gulps.

His hands shook as he held out the mug for a refill. He drank half of it before sitting it down.

“Me grandmother used to tell us when I were a lad,…. “ He finally began, then went silent. Everyone leaned in, waiting.

“She told us, and she said her granny told her, and her grandmother and her grandmother…..” He took another swallow. “I allus thought it was a tale the old women told the children to keep them from running wild in the woods at night… But….” Another long drink.

“What’d ye see, Robert?” the woman two stools down asked. Maggie, on the wrong side of 45, owned a little food store nearby, and, not to be unkind, was a bit on the prissy side, single, and likely to stay that way. She was irritated that he’d brought mud and manure in with him, too. Neat and orderly things appealed to her. Bob Mordrum, being neither, did not.

The village was off by itself in an empty corner of a rural county surrounded by a great, ancient forest. It had the air of a place that had been bypassed when modern times blew through, and preferred it this way.

A single road, no more than a paved path, really, came in one end of it, passed by the pub and a few small shops and some isolated houses, and dove out the other side. Few cars came through, though.

The Black Crowne pub was nearly as old as the village, it’s thatched roof’s beam sagging in the middle and the rest dim and dingy with age inside and out. It had been whitewashed once upon a time, back before the Great War, but the stones of the walls were showing through everywhere now. A thin string of smoke from the fireplace emerged into the thick night air, and just hung there.

The old man at the end of the bar raised his mug and the landlord refilled it brusquely, then went back to lean against the counter in front of Mordrum, arms crossed. The old man looked disgusted.

The landlord’s wife came out from the back room and stood by him, stolid as one of the large hand-hewn posts that held up the first floor above—and almost twice as big around.

“What story was that, Bob?” she finally asked. “What story did all those grannies tell the children?”

“Of the earl who betrayed his master and stole the girl he fancied,” Mordrum said. “And how the master repaid his treachery.”

A couple of heads nodded slowly, the memory of the story coming back to them. Everyone had had a granny, apparently.

The old man at the end of the bar sat a little straighter and started listening with more interest.

The village was surrounded by giant oaks and maples and hemlocks, some six feet across that had been growing since the English Civil War. The permanent green-tinged gloom that blocked out the sky tended to encourage dark thoughts of murder and betrayals.

People in these parts have been murdering each other for centuries, as it happens.

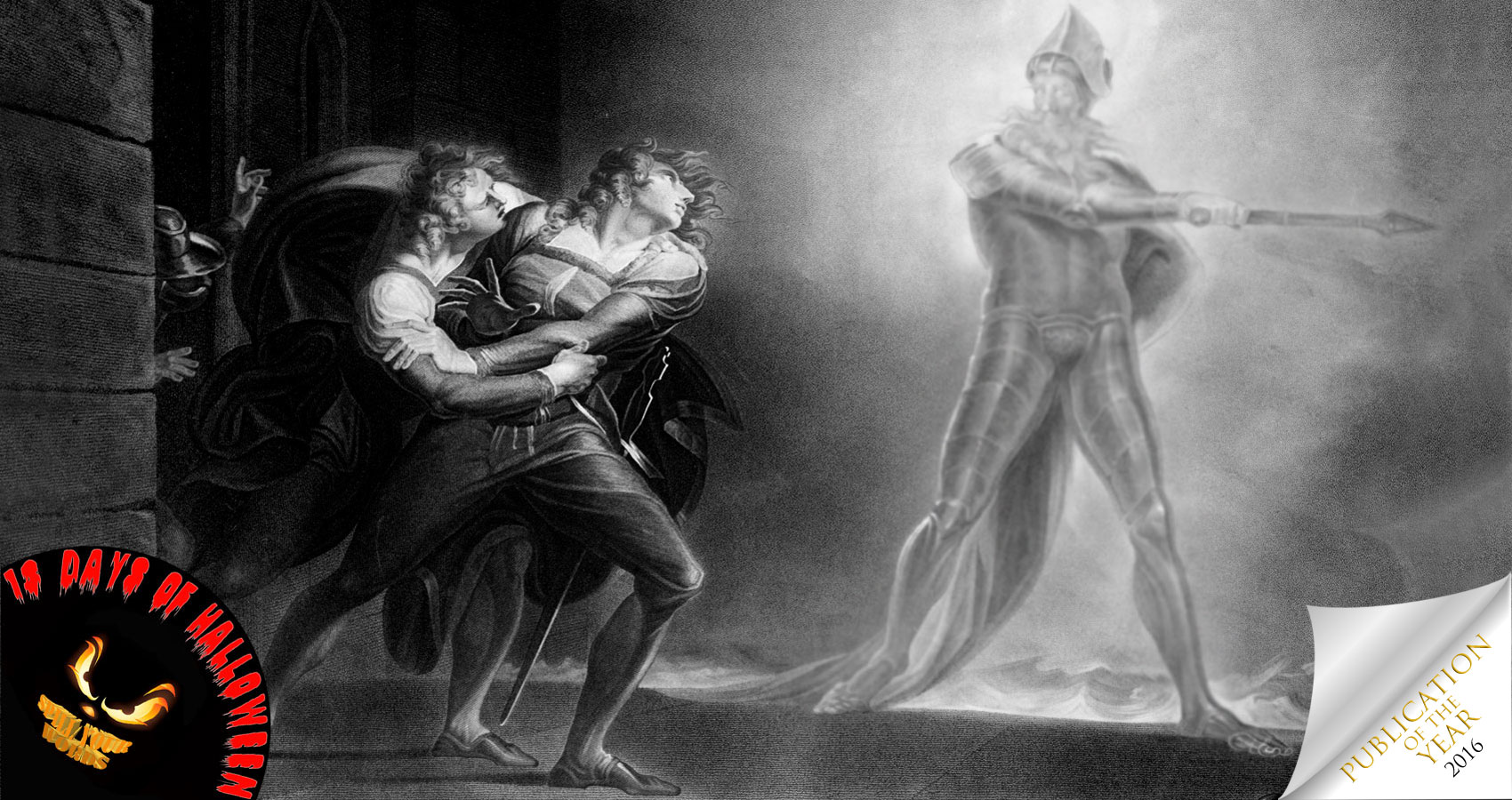

One such story of a dark deed from pre-Norman times had persisted. It said that the shade of an ancient earl wanders the wood only during a full moon in late October, moaning and groaning, crying out as he tries to pull a spear out of his belly. In the pale light in a particular opening in the endless forest. He’d been murdered by an ancient king over a woman, it was said.

“I seen him tonight, in the glen” Mordrum said, draining the mug and gesturing for another. “The Earl granny told me about. The ghost of the earl, I mean.”

A murmur went around the room. They knew the spooky, secluded glen well.

But Maggie just sniffed at his statement, accidentally getting another whiff of the filth on the man’s boots and curled her lip into a sneer.

“Are you sure you haven’t taken a pint earlier, Mordrum?” she asked with a tone that said she thought he’d had more than one.

“Ah, Maggie,” Mordrum said without looking in her direction. “It’s always good to see you. My evening’s now complete, and I can die happy. How’s that search for a husband going?” She rose, intending to slap him a good one, but a man put a hand on her shoulder.

“Nay, lass,” he said. She sat back down.

No one said anything more for a moment. In the silence, the old man at the end of the bar stood and walked over to Mordrum, and waited politely for his presence to be acknowledged.

“Where was it that you saw this….thing, Bob?” the old man, who was generally only known as Old Stephen, asked when Bob saw him and nodded.

Mordrum studied him, looking for a sign of mockery, but only saw serious eyes set deep in a wrinkled face.

“Are ye seriously wanting to know, Stephen?”

The other nodded and waited. “I have a reason to ask,” he said.

So Mordrum told him, told the room, that they know the spot. A glen, a clearing near a cliff below which a stream runs. Near the ruins of an ancient bridge, where the stone piers sit in the fast-moving water, covered in moss.

Stephen nodded once. “I know the place,” he said. “I saw him once there, when I was a very young lad.” The two women laughed. “It’s true! I couldn’t have been more than 6 or 7, and had sneaked down there on a dare. It were about this time of year, too, All Hallow’s Eve. Nearly 70 years ago this very night.

“He was in a shaft of moonlight on the banks of the stream by that cliff, him all covered in chain mail and moonlight.

“But he had a spear sticking out of the front of himself, and blood was running like the stream. He were crying out something awful, begging someone to pull it out. Gore was everywhere.

“But the thing was, you see, that I could see the ferns and trees right through him.

“Right through him,” he repeated, slowly.

“I ran. I ran like a deer with a wolf behind him, all the way to my widowed father’s hut. My granny was there, and she grabbed me and calmed me down, because I was sobbing and crying so I could barely speak. Once I could talk, and she got out of me what I’d seen, she sat back and was quiet for a long time. Only then she told me.”

She told him the story of King Edgar the Peaceable, who completed his grandfather Alfred’s task of uniting the Saxon kingdoms into a new one, England, 100 years before the Normans landed.

“He ruled in these parts, 600 years before the reign of Henry VIII. Before kings had numbers. When all maids were fair maids and all knights were gallant and life was simple. And violent. And brief.”

As the story went, Edgar had finally stabilized the kingdom and decided it was time he took a bride for himself. Reports had reached him of a maiden so fair that woodland creatures, predator and prey, came and lay down together at her feet. So, he sent one of his earls to appraise her and report back.

The earl, both deceitful and cunning, and secretly part of the rebellion Edgar had crushed, went and looked, but sent back word that her attributes had been much exaggerated.

The real girl, the earl said, feigning regret that his lord had been so misled, had eyes that looked at one another. And since one leg was longer than the other, he said, she tended to walk in circles.

The earl was lying, of course, because when he had seen how beautiful she really was, he wanted her for his bed and forgot how dangerous lying to a king—this king— could be. So he sent back the false report, then seduced and married the girl himself.

In short time, though, word filtered back and Edgar discovered the earl’s treachery. He took a group of mounted Jarls, chased the Earl and ambushed him in that same glen under a full moon on All Hallow’s. The war party trapped him against the cliff, where the king dismounted for personal combat and finished it by shoving his lance straight into the traitor’s belly. He told his men the body should be left there to rot and feed the buzzards, without benefit of Christian burial. The man’s soul would never

have peace, he decreed.

“But… What happened to the girl, Stephen?, Maggie asked, curious in spite of herself”

“Why, it may not surprise you to know that she married Edgar,” he said, signaling for another pint. “They married in the greenwood and lived happily ever after.”

“I suppose she had no choice,” Maggie said. “Women have always had to adapt themselves to what men decide.”

Stephen continued without replying, used to Maggie’s sharpness about men. “The country folk have long said that the false earl—and only on the date he was paid back in full, under an All Hallow’s moon—can be seen in the glen, tugging at the spear, crying out, begging for mercy.”

That was too much for Alice, the landlord’s wife.

“Pffft… You’re getting daft, ye old tosser. I don’t believe in ghosts,” she laughed without smiling, her arms still crossed.

“I’ve seen lots of spirits in here, I can tell you, but they all came out of a bottle.” Stephen’s face was impassive. He took another sip of beer.

“Much the worse for you, then, Alice,” Mordrum said from the other side, weaving a bit on his stool and his words slurred, “as that’s when they can sneak up on ya.”

A young couple from America was at a corner table, finished with a late meal and drinks and some pharmaceuticals for desert, and largely ignored by the locals. They were staying in one of the bedrooms of the inn above the pub, and had been listening to the conversation about the murdered earl with growing interest. The young man, dressed in a button-down oxford shirt and khaki pants, sauntered over to the group at the bar, a little unsteady, the beer apparent, the pills just kicking in.

“We couldn’t help but overhear,” he said. “A ghost, you say? A real one?”

Stephen and Mordrum looked him up and down, and Mordrum said “Aye. He’s real, all right.”

Alice made a clucking sound in the back of her throat.

“He’s real,” Mordrum said again, glaring at her. “What’s your interest in our ghost, lad?”

“Could we see him, too? A real English ghost? That would be a story to tell back home.” His pupils were wide and bright. He seemed happy. Too happy.

No one said anything. Mordrum looked at Stephen, raised an eyebrow, then back at the boy.

“Why not?” he said, a small smile playing with the corners of his mouth. “It is Halloween, the moon’s still full, and it’s not far from here. Maybe that’ll be a good way to convince her ladyship here” tipping his head at Alice— “that her prejudices are as stale as the stout.”

Her husband, the landlord, swelled up and crossed his arms, too.

“That’s enough of that, Bob,” he said quietly. “You’ve never made any complaints before.” Bob shrugged an apology.

The girl rose from the table and joined the young man, her eyes a little bright, too, and her cheeks rosy from the drink…and the desert. She wobbled a bit on the way, and steadied herself on the boy’s arm.

“That would be so neat!” she said. “Could we go?” She frowned a bit, the effort of thinking showing, and looked at Bob and Stephen. “But someone would have to show us the way.” The boy pulled a small roll of notes from his pocket and put them on the bar.

“This is for the meal and drinks, but there’s some extra there for anyone willing to guide us.” Alice carefully extracted some of the bills and put them in her apron pocket. She looked at Bob and Stephen and smiled slightly. She shrugged.

“I think you two would make perfect guides, if you aren’t so far in your cups that you’d get lost on the way to the door.”

As her last words settled on the room, all heads turned at a roar from the path outside.

Hoofbeats. Lots of them, and heavy horses, too, from the sound of it pounded the night air. The mugs on the bar danced from vibration, the liquid inside moving in ripples back and forth.

It sounded like heavy cavalry. They had all been to battle reenactments in the county, enough to know. Above the din, they heard the sounds of rough male voices shouting in a strange language, urging speed.

“What was they shouting?” Maggie said. “Was that German?”

“Nay, Maggie,” Old Stephen said, a strange look coming over his face. He was something of a historian, among other things.

“Not German. That’s the language the Saxons used. We once had to read the original in school, I’m talking about Beowulf. ”

Without a word, everyone in the pub moved to the old wooden door. Bob somehow got there first, but everyone was close behind him. He flung it open and stepped out. Maggie pushed past him, and Stephen. The young couple and the landlord and his wife followed out into the night.

There was nothing there. No horses, no knights. No cars or heavy lorries. Nothing but silence under the full moon.

“Does anyone smell that?” Maggie said, sniffing.

“Can’t be….” Alice said. “There’s nothing here.” She looked confused. Surely the re-enactor group would have stopped, wouldn’t they? They were just from the next village over.

“I smell horse sweat,” the American girl said, and giggled oddly. She giggled more at the questions the others looked at her. How would you know, you silly girl, they thought?

“It smells just like my horse back home after a workout.” She sounded a little defensive.

Alice gathered her sweater about her and hugged herself. The air was cold, too cold for a natural thing this time of year. She didn’t say it out loud, but she knew that smell, too. Horses. Lots of them. And leather.

But there was no other sign. A deep unease settled on her, but she said nothing more. She wouldn’t give Bob the satisfaction.

But the re-enactors would have stopped…

“Let’s go!” the American boy said.

Bob nodded, looking at Stephen. “I’ll go, but old Stephen here has to go with me. And Alice. I need witnesses.” He was not really eager, because he’d seen what he’d seen and didn’t really need to see it again, but now, with the group around him, he felt he had no choice but to play it out. In answer, Stephen took half of the money on the bar. Bob pocketed the rest.

He put on an air of resolve. Besides, Alice’s taunts rankled.

What is the nature of the boundary between the worlds of the living and the once-living? It is blurred and permeable, filled with guesses, with misunderstandings, with tall tales and inventions, with old grief thought buried, but still alive to come squirming back to the surface late at night.

How Far?

“How far is the glen?” the American asked, his alien accent irritating them all for some reason. “Do we drive or walk? I have a rental, but it’ll only hold two or three besides Nancy and me.”

“I’ll drive me van, too,” Bob said, looking at the muck on his boots. “Come along, any who wants to ride.”

The group piled into the two vehicles and headed unsteadily out of town, with Bob in the lead.

No one had thought to bring a lantern or flashlight. They parked by the path to the glen and milled around, until Bob remembered he had a torch in the van. He dug it out, banged it against his other palm once or twice before the battered old thing shivered to life with a sickly, yellowish beam.

“That’s just brilliant, Bob,” Alice said in the darkness behind him.

He muttered something under his breath, then headed into the woods.

“There’s a full moon, so it won’t matter. Stay close.”

The Americans were right behind him, both giggling now. The other women came next, then the landlord and Stephen.

“Watch your step here,” Mordrum’s voice called out. “It gets a bit steep up ahead.”

The group followed, single file. Shafts of moonlight here and there lightened the gloom a bit, but halfway down the hill to the stream a crashing sound startled them all, and then some cursing by the landlord filled the air. Bob paused and aimed his weak flashlight back at the fallen man, who was extracting himself from some vines and feeling at a spot on his forehead where there was some blood leaking.

“It’s not far, now,” Stephen’s voice said from the rear. “Try to be quiet.” The landlord grabbed his handkerchief from a pocket and pressed it against his forehead.

Mordrum slowed the pace and picked his way down the hillside. The others followed, more carefully now.

He stopped at the bottom where the space opened up, with the light aimed at the soil. It was obvious. The leaves and soil had been churned up by the hooves of many, large horses.

The others bunched around and looked.

“Horses,” the American girl said, stating the obvious. “Big ones.” Bob shone the light on her, and was startled to see that her eyes were big and round, and on her face a wild kind eagerness. Her cheeks were bright red.

They stared at the clear imprint of shod hooves in the spot on the bank, not sure what to do. There was no sound other than a distant owl, and nothing moved in the woods. Up ahead, the glen was open to the full light of the moon, with a dark and towering cliff on its far side. The light seemed to shimmer.

Bob stood frozen and no one else moved. But then Stephen pushed his way through the clump of his neighbors to Bob and held out his hand. Bob gave him the flashlight, and the old man took a step toward the glen.

“Well?” he said, turning and looking at the others.

Alice was the first to follow. “This is ridiculous. And I’m cold. Let’s get this over with and go home.”

The American girl rushed around her and ran ahead.

The landlord, Maggie and Bob stayed behind. The American boy took a few steps toward the glen, but stopped short as the other three went on ahead. This much they all agreed on later.

The Inquest

Testimony at the coroner’s inquest, held to determine the cause of death, was full of unbelievable things. Contradictions. Shame.

Bob, Maggie and the landlord said all they heard was a sound of shouting down and away from them. Down by the cliff, men’s voices shouting in a foreign tongue. They all said they heard a woman scream.

It was too dark, though and they were too far away to see anything beyond vague impressions. Maggie said she saw moonlight glinting off of what looked like armor and drawn swords. There was a terrible clatter in the glen, then silence, after the scream.

The American boy couldn’t say much of anything intelligible, and was still in the psychiatric wing of hospital, completely detached from reality.

“They killed him, they killed him,” were the only words they could make out. He had been sedated for much of the time since that night, and the doctors said he might never come out of it.

What he said made no sense, though, because the only person who was deceased was his girl, whose body was lying face up in the glen, at the base of the cliff, eyes wide and mouth frozen in a scream.

Suspects were considered, examined and eliminated. The re-enactors from the next village all had solid alibis for that evening, and were excluded from any suspicion.

There was no visible cause of death on the body, however. The autopsy found no wounds or trauma. She was young and in otherwise good health, other than a slight defect in a heart valve. Toxicology found traces of hallucinogens in her bloodstream, psilosibin, or “magic mushrooms”, in addition to a bit too much alcohol in her. The boy had the same drug in him, enough so that both were severely impaired, subject to hallucinations and euphoria.

“Heart failure due to unknown causes,” the official report said. No one was willing to say that she had died of terror. But unofficially….

The stories Alice and Stephen told settled nothing. Alice, despite being close to the alleged action, steadfastly maintained, after first telling a constable about horses, that she saw no horses, no mounted knights, no earl and no angry king. Nothing could shake her story.

She only said that she saw the girl move ahead of her and Stephen, as if in a trance, and walk to a spot at the base of the cliff where the moonlight was brightest. The girl, who Alice said was drunk and acting strangely anyway, spread her arms as if to embrace someone, or maybe to hold two people apart. Then, Alice said, she arched her back and screamed, as though she’d been stabbed from behind, and fell lifeless onto the thick carpet of leaves.

And with that story, Alice refused to say more.

“She was on drugs,” she said. “Who knows what she saw.”

Stephen’s Story

Old Stephen was reluctant at first, but he finally just let it out. He was too old to care what anyone though, he said.

His full story was quite different. But it did not vary in any detail, no matter how often he was asked to repeat it, and despite the open skepticism of the detectives and solicitors when he was on the stand.

And this was what he said he saw.

“Me and Alice and the the girl were standing in the glen, the boy froze up and stopped several yards back, and all the others some distance further back still. We all heard horses coming, and then there they were, a group of armed men suddenly appearing on the bank downstream, all covered in chain mail and waving swords and spears.

“At their head was one who was dressed better than the rest, and his livery had a crest on it.

“It were just like my granny told us, I realized. That was the old king, Edgar, and his bodyguard, finally cornering the unfaithful Earl against that cliff. I saw him there, too, the Earl, I mean… kind of pale blue in the light, as they all were. Things were kind of sparkly. He was dismounted, and had a sword in his hand, all defiant-like. He was a handsome devil, I must say.”

Stephen swore that the others pulled up and the king dismounted, a battle axe in his left hand and a javelin in his right. He strode up to the man by the cliff, and their mouths moved. They were arguing, but without sound.

“The men were getting more and more angry, shaking their weapons at each other, and that’s when the girl stepped forward, in between them, as though she were trying to stop the fight. But she kept staring at the face of the earl. She was transfixed by him, it was plain.

“The air was electric and it was as though all time had stood still in that spot, in the moonlight. Leaves falling from the trees hung in mid-air, mist swirled all around, but froze near the figures. Only the girl and the men moved.”

“It was sudden, and her back was to the king. But he lunged forward with his spear, pushed the ghostly death of it right through her and into the belly of the Earl. That’s when she screamed and fell to the ground.”

What happened next, the presiding officer asked him?

“Well, it was strange. The king—and I took it to be him, because of how he looked and the size of him— and the mounted men just sort of disappeared. The girl was lying on the ground and there was the earl, or his shade, standing, begging someone to pull the lance out of him. I can’t remember much after that until we were back at the cars and the police were questioning us.”

Case Closed...

The official coroner’s report said that the girl had died of natural causes, most likely a heart attack due to a faulty heart valve, too much to drink, combined with psychedelic drugs and an extreme, but unknown, shock. They assumed that Old Stephen was suffering from early dementia and gently pushed his testimony to the side, although he didn’t seem to take it personally.

The inquest further found that the whole adventure was probably the result of a group of superstitious villagers who, having had too much to drink, decided to have a little fun with some impaired outsiders, and took the old legend about King Edgar and the faithless earl too far.

*Case closed. *

The villagers slunk home, and never spoke of that night again. Maggie eventually moved in with her sister up north. The pub closed within a year and the landlord and Alice left for parts unknown, the ramshackle place vacant to this day. Old Stephen lived out his days, alone, in his cabin, and Bob sold his farm. The rumor was that he’d gone looking for Maggie.

Two things were not resolved in the coroner’s report, however.

At the scene of the tragic death, at the glen, technicians had made plaster casts of hoof-prints at the edge the stream. These were explained away as being left by some passing horses and riders, as people in the area did keep horses. But the marks of the shoes were of an unusual nature. In fact, had anyone bothered to check with a museum, they were of the style of horseshoes from more than 1,000 years earlier.

But the final thing wasn’t actually found until long after the inquest. A treasure hunter with a metal detector was looking in the glen one day, months later. Near the base of the cliff, buried quite deep, he got a strong signal. He grabbed a shovel and dug until he hit metal. Carefully, he excavated earth all around, until he pulled up the heavily corroded tip of a large military spear, and around it the bits and pieces of old chain mail and a helmet.

As he laid the pieces out on the ground by the hole, a sudden breeze swept up the stream and over him, and bent the trees all around. He thought he heard the sound of a young woman’s high laughter.

Then it was gone, like a sigh. An owl hooted in the distance.

He packed up his finds to carry out of the ancient woods, already thinking how much he’d get for them on Ebay. But, he had a bad feeling from the place.

He hurried, uncomfortable in that gloomy, lonely glen even in fulldaylight.

A low sound came from behind him as he climbed up the hill, from the direction of the cliff. Soft and distant, it sounded like a moan.

He climbed faster, not looking back.

- Epilogue - May 2, 2020

- A Morning - April 10, 2020

- Giving Back, Reluctantly - March 20, 2020