Autumn Festival

written by: Jamal H Goodwin Jr.

@Jaygoodwin171

“Well hello there young man.”

Her voice, sweeping and powerful. A wave crashing against the tide, splashing cool water amid the docks at dusk. Her voice, deep and respectable. Low resonance, low like the pitch of a tuba. Deep, steeped in knowledge. Only one woman was powerful enough to convey her being through a mere sentence. That woman was a friend of my mother’s.

I cleared my throat. “Hi Terry. How are things?”

Seeing her out here was a surprise. She was sitting on a stool planted in the dry autumn grass. Across the meadow, her students were daubing landscapes onto their canvases.

“Thomas. A pleasure to see you always. My morning is going well, thank you for asking.” She smiled a secret smile. I gulped. Sweat droplets formed on the side of my head. Terry was a master artist. Just like my mother, she was everything I aspired to be. Unlike my mother, Terry didn’t raise me and shower me with love. A strong black woman, skilled in her craft, while I was an amateur.

She asked, “Have you seen Susie? She’s back in town.”

“Yes. We just had breakfast together.”

“That girl. As spry as an elk. I knew she’d be happy to see you.” She inhaled, savoring a breeze. “You should be glad she’s here. Only a town like Haroville could allow a flower like her to shine.” Haroville. A Pennsylvania town too small to be marked on a map yet sprawling with more life than a city. Or so I was told. I had lived here my whole life. I wasn’t even in college, unlike my best friend.

“Yeah,” I said. “I don’t know what I’d do without her. Even now she lifts my spirits when I’m down.”

“She’s a blessing and a half. What else is new young man? How’s your drawing going?”

“Still working on it. Just when I was having a breakthrough Chuck sent me on an errand.”

“Oh.”

“No worries, I’m hopeful.” I looked to the meadow, her students still hard at work. Bright splotches stained their aprons but they hadn’t noticed. They were a small bunch, all high school age. “How about you Terry? How’re the lessons?”

She inclined her chin towards the students. Their eyes sought the sky or the trees, wholly indifferent to their canvas. Perplexed, I wrinkled my forehead. In sketches I’d memorize the landscape and focus solely on the drawing paper. Terry was calm, her eyes nearly closed.

“The canvas is a distraction,” she said, as if hearing my thoughts. “Beginners stress getting the painting as close to real life as possible, but they’ll always miss something.”

“I didn’t know that.”

“My students make me prouder every day,” she said, then laughed. “Of course, they don’t make strokes like I do. But that’s the point. They think they’ll learn my style and surpass it, but they end up creating something completely new.”

I thought of the framed painting tacked above my bed. The orange sky, the hills. The sun pulling tidewater upon itself like a blanket. Mom made that.

“My offer is still on the table, Thomas. Become a student. Discover the picture your heart is yearning to paint.”

I shook my head.

“Thanks Terry, but I do pencils, not brushes. I’d like to draw in the style Mom painted in. If that’s even possible.”

“Eunice Hartley. She had a talent I’d never forget. Small strokes, bright colors, always in a gradient. It was as if time passed from left to right on the canvas. If it wasn’t for her I’d never have left Philly. Never would have started teaching.”

My heart grew warm. 10 years had passed and yet she lived on.

“Thomas, I don’t know how you’ll pull it off. I know you put pressure on yourself. Sometimes you try too hard. Sometimes you don’t try hard enough. But Eunice was my best friend. A piece of her lives in you. Relax, and then draw. Make mistakes. Then relax and try again.”

“I will. Thanks for the advice.”

“Whatever is meant for you, you will achieve. It may not look like Eunice’s success, but it will be yours. I’m rooting for you.”

She opened her arms for a hug. I embraced her, a fire kindling within me.

***

On my walk home I noticed several bushes of unripe tomatoes. They were on the outskirts of town. The thick, branching stalks shimmered beside the brown grass and fallen leaves. Odd, considering tomato season ended in September. The bulbous green fruit would be juicy once it finished growing. Maybe I’ll come back. Take some to plant in the backyard.

***

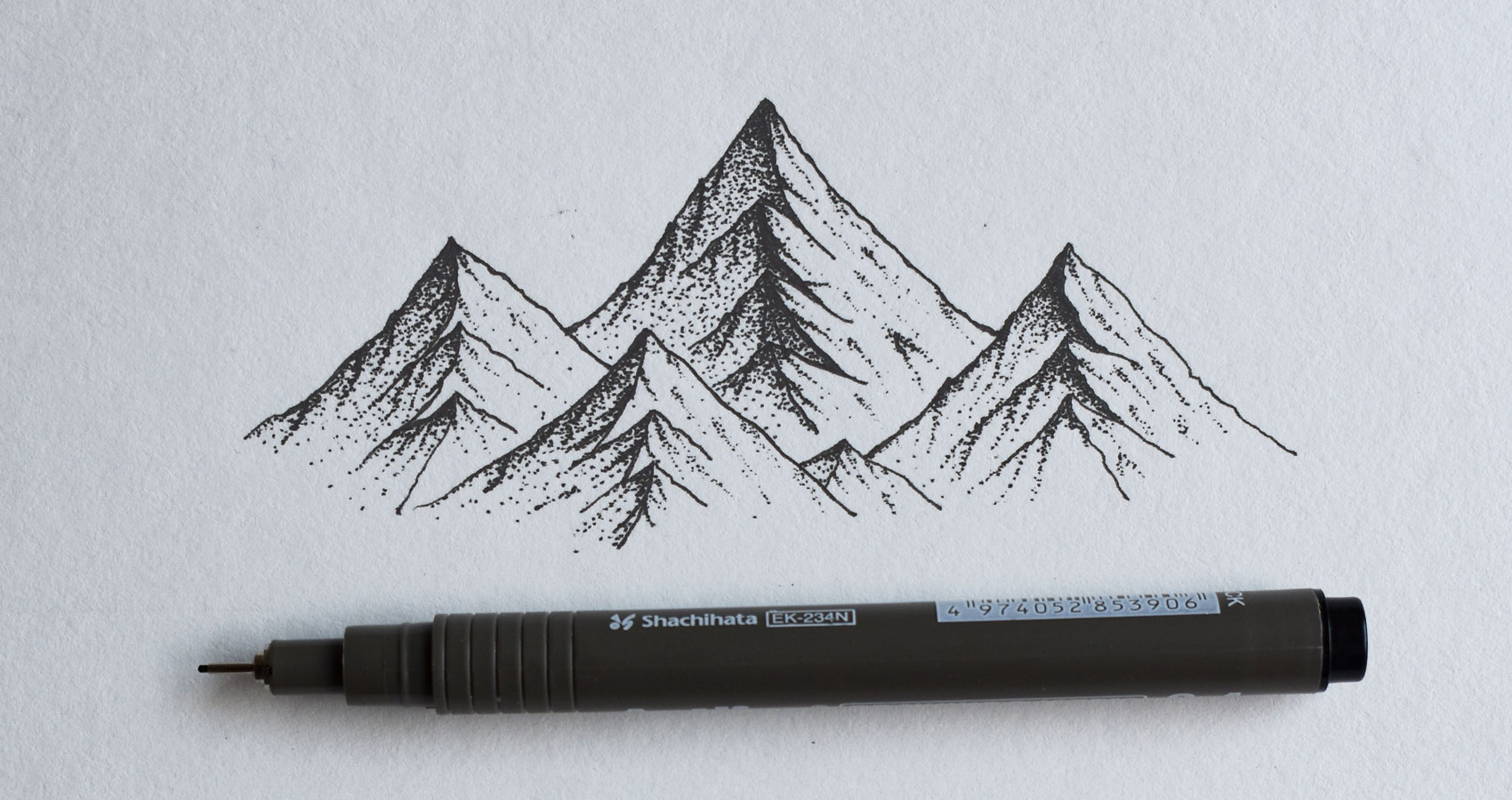

When I opened the door to my room, hot air rushed into my face. The heat was finally on, thank goodness. I took in the warmth and let out a breath. My pencil and paper sat atop my desk just the way I left them. All that was left was to regain my artist’s high. I stood over my desk, observing my paper. Gray humps were sketched. They were supposed to be hills. Mountains.

After a quiet sigh, I crawled in bed. Above me, Mom’s painting hung by a thread tied to a nail. The tiny pink string—that could have been from a sweater or a spool of yarn—was lifting the weight of the world. Gravity’s crushing hands tugged on it relentlessly, yet the strand held firm. The painting it carried: soft dabs of vivid sunset at the docks. Light retreating to the sun and shade emanating from the grass. Dark ocean water rose to meet the sky. Restless beauty was captured on that frame, beauty that could just barely be contained. That thread was keeping life alive.

My pencil humps, haphazard scribbles, lolled on my page. It would be long before I could create life through art. I raised my head and gazed at my drawing a few moments more. No, I’ll get to it later. There’s plenty of time.

It’d been a while since I chatted with Lincoln. He and my other friends left Haroville a few years ago. In grade school Link and I would spend hours watching movies, or we’d go get lost in the woods. Now the only time I could see him was at the Autumn Festival—if he decided to show up. That loghead was in his fourth year in college and hadn’t stuck with a major. I called him.

A groan hovered from the line. Then static.

“Link?”

“…Thomas? What’s up man.”

“Buddy, why are you asleep at 12 PM on a Thursday? You should be in class.” Another groan.

“No… It’s finals prep. No need to sleep in class when I can sleep in bed…” Link was never a go-getter. It’s a wonder he was able to leave town while I had to stay.

“Take a walk or do something, Link. We don’t get to chat so often.”

“Okay. Alright Thomas.”

He paused, probably stretching in his dorm-bed. I couldn’t imagine waking in a place far from home, free to explore unseen sights. By senior year of high school Link and I had climbed every last tree in the woods surrounding Haroville.

He said, “Alright. Well, what’s new?” I grinned.

“Susie’s back in town.” I could almost feel Link’s smirk growing over my shoulder.

“Oooh, is she? I bet you’re the first person she saw. How’s she doing? Your ‘angel of Haroville?’”

“You’re never gonna live that down, are you?”

“Nope. You should call her that again and see if she still blushes.”

“I’m good, thanks.”

“She back from another business trip?”

“Yeah, she’s visiting for the Autumn Festival. Haven’t seen her folks yet but I’m going to help her babysit Edna in a couple days.”

“Hey, that’s nice of you man.”

“I like to help where I can. Susie’s a little down. Stressed about joining the family business. Anything that cheers her up I’d do.”

“Really nice man.” He paused again. “Have you asked her out?”

“Huh?” I said, though I heard him and saw the question a mile away. The thought loomed in my mind anytime I talked to anyone who wasn’t Susie about Susie.

“Susie, Thomas. It’s been you and her in town the last four years, besides the kids and the grownups. Have you made it to the next level?”

“The next level? First, that’s cheesy, don’t say that. Second, we’ve been close since childhood. If I tried to get with her now she might be scared off. She’d fly off to Birmingham. The British one.”

“Hah, her rich-people money. I’d personally go to Tijuana.”

“Do you think if I tried to get with her now she’d be scared off?”

His laughter rang in my ear.

“Ah, what the heck.” He said. “I’ll stop by next week for the Festival.”

***

Silver light slithered through cracks in the blinds. A shimmery mural dotted the carpet floor. It swayed with the shadow of tree branches rocking in the wind. Serene, this morning. Six days until the Autumn Festival. Today was the day. My artist’s high was coursing through my veins. I shoved off my blanket and trotted to my desk. White paper. Gray humps. Pencil liftable at a moment’s notice.

“Thomas! Get yer butt down here.”

Foiled again. Oh well, I could always draw another day. What could Uncle Chuck want at this hour? It was only… 1 PM. Maybe I overslept a bit. I closed my door and marched down the stairs. Chuck was glaring at me as I reached the bottom.

“Yes sir?” I said half-jokingly.

“Tom, you never said anything about babysitting Susie’s sister. What if I needed yer help with setup? And did you drop that letter off to Mayor Johnson like I asked?”

“Yes I dropped off the letter. And you usually never need my help. You’ve always crafted the small stuff while the builders handled supplies.”

“That’s just it m’boy. We need more supplies. Those giant screws are hard to come by and we need em for the wooden horses. Johnson has to order more for us. We’ve only got six days to get it all ready.”

There wasn’t anything I could do. Mayor Johnson was always holed up in his office. Our town was a peaceful one, and he kept busy to assure it stayed that way. Even if I wanted to help Chuck I didn’t know the first thing about drilling tables, sawing wood, or wood carving.

“I’m sure he’ll write back to you,” I said. “If not he’ll at least get his phone line fixed.” The mayor didn’t favor up to date devices like cell phones. Then again, most in Haroville didn’t.

“Right. Run along then. Go see yer girlfriend before she leaves again.”

I winced. He wasn’t trying to be rude, but that hurt and he should know it. Chuck was the reason I still lived here. Jobless. Not going to college. He wouldn’t let me, and for four years I’d been too scared to ask him to change his mind.

“Y’know Chuck, I am 21.” I let out a sigh. “I’ve made peace with losing Mom. I don’t think she’d want me trapped here.”

“Shut yer mouth boy!” He snapped. In an instant, he was seething. “Don’t talk about my sister like you know what she wanted. She was born here and she was buried here. Want to leave yer mother alone? Want to die in the city so her spirit’ll never find you?”

I took a step back. My heart was racing.

Chuck huffed and stomped out of the room. An electric saw started buzzing from the garage. He was back to work on his woodcrafting.

***

The Autumn Festival was celebrated every Thanksgiving. Each year it had a different theme and this year it was ancient Greece. Walking through town, I saw houses with floral wreaths hung on their doors. In the town square were marble sculptures of the Greek gods and goddesses. Zeus embracing a lightning bolt with a glare of magnificent fury. Athena clad in armor and poised with her bow—aiming off towards the woods of course, not to anybody’s house. Poseidon had arms outstretched in a mocking gesture, waves surrounding him. There were others, too, but the main trio took center stage. Surrounding them were wooden horses as well as wooden pedestals and columns Chuck had crafted. On the display’s edge were granite sculptures of ‘supporting characters.’ Goddess Circe in her lonesome glory and a haloed, angel wing’d Icarus.

On this quiet Sunday, the sun lit all in its path. Yellow rays beamed upon the fountain water. Houses were tinged in the light, giving them life that hasn’t been seen in a while. Chirping birds flew by, squirrels rustled trees. Sweet cinnamon tickled my nostrils—Mrs. Thompson was baking an apple pie for her grandkids. This sunny, chilly afternoon, most were inside with their families. In the square I felt a longing. For new sights and sounds. What was an art studio like? What sounds were heard on a city morning?

My longing weighed me down. It was something that returned every now and again. It was why I couldn’t always focus on drawing. Friday was when Chuck blew up at me for disrespecting Mom, but he said something yesterday that had me perturbed.

“Haven’t seen you drawin’ much m’boy.”

It was so hard to focus. To be inspired. If I traveled somewhere new I could be. But would I be? Practicing now was hard enough already. I could be bad everywhere.

I walked round the fountain and towards the east end of town. Susie would assuage my fears. Her wide smile, her cheerful voice. I could almost see her blonde hair stirring in the breeze. It was radiant in sunlight. As I neared the end of town her mansion came into view. I’d be there tomorrow, too, while I babysat Edna. Before Susie’s mansion was the last house in a row of houses. Three figures were sitting on Windsor chairs beside its stoop. Sandra and the twins. I walked over and waved.

“Thomas!” Andrea shouted.

“Thomas Hartley!” Sarah shouted. Sandra smiled, rubbing her daughters’ shoulders.

“Hey guys!” I said. “How’s it going?”

“Goood,” they answered. “We’re helping Mom with pottery.” Sarah said. The two were covered in brown splotches on their face, fingers, and clothes.

“Wow, pottery. Sounds like fun. Is it tough?”

“It’s like making a cake or a mud pie,” Andrea said. “Only, you can’t eat the clay.” We all laughed. Sandra pinched Andrea’s cheek.

“What brings you through here Thomas?” Sandra asked.

“I was just on my way to Susie’s place.”

“Oh, I’m not sure it’s a good time.”

I raised an eyebrow. “How come?”

“Mr. and Mrs. Clarke are convening with her. No one’s left the mansion in two days.”

Of course. Susie’s father, Mr. Clarke, was a bonds salesman. His fortune was made off the debt of millions, affording him a comfortable living in our quiet town. He’d been trying to get Susie in on the family business, but she just wasn’t pleased by it. Susie was a nature person, not a numbers one. She often voiced her disdain of the financial jargon her father coached her on. Mrs. Clarke, a benevolent woman and a faithful wife, was torn between her daughter and her husband.

“It’s that bad huh?” I said. Sandra nodded.

“Otherwise, how are you?” She asked, changing the subject. Good thing she did. I wouldn’t want to seem dour in front of the kids. “Your uncle made such great sculptures this year.”

“He did. Chuck wouldn’t give up woodcrafting for the world.”

“The smoothness of those pedestals, and those contour lines etched in the wood. You can see his years of experience on its surface! Once you get those years on your belt, you’ll master your craft too, Thomas.” An image fluttered into mind: my pencil, paper, and desk. It vanished as quickly as it appeared.

I said, “I’m glad Chuck’s able to craft to his heart’s content. That’ll be me, someday.”

“Mom, Ms. Terry is a great artist. She gives us cupcakes.” Andrea said with a grin.

“I love her cupcakes!” Sarah said.

A deep voice shouted, “And I love giving them to y’all!”

I turned and saw Terry waving her hands ecstatically. A pang trembled from my chest to my fingertips. My heart gripped itself, pulling inward, attempting to retreat since my legs froze in place.

“Ms. Terry!” Sarah and Andrea shouted. They ran out their chairs and hugged her.

“Hey girls, aren’t we in good spirits today?”

“Yesss,” they said and explained what they were doing.

“That’s very good you’re helping your mother.” Terry said. “Family is important. They help you grow and you make them happy.”

Sandra and Terry greeted each other. Then Terry looked at me.

“It’s good to see you, young man.” In all my years knowing her, Terry always smiled with such ease. It was as if she surpassed a struggle every day of her life, so she was not only sagacious, but she also was untroubled by everything. My heart was pounding. The situation was so silly. If she asked how my drawing was going, I could just tell her I was working on it. But was I? In the four days since I started, I hadn’t come up with a plan or even touched my pencil.

“Hi Terry. Good to see ya.”

She pulled cool air into her nostrils. Slowly, she exhaled. Her gaze shifted from me to the woods. The twins held her hands, enamored by her aura.

“The Festival will be here soon. Did you know, Thomas, that autumn is the season of decline? I don’t just mean the trees. Squirrels are packing their stomachs so they can sleep the next season. Birds are migrating to warmer dwellings. You see, the experienced labor in the warm weather while everyone else is out playing. Autumn is the time the experienced begin to close up shop. They have a respite before work begins anew in spring.” She laughed, still with her cordial smile. “Thomas, you are a light who’s yet to bloom. Hurry up, before the season ends.”

***

Was I immature? Undisciplined? In front of Terry, no words or questions came to mind. Now the queries were overflowing. I was pacing my room, still unable to draw but not able to relax either. If Mom were here, she could have shown me some techniques. Not everything of course. But I’d have someone to push me. I wouldn’t have to feel guilty.

I rushed to my desk, gripping my pencil. I whirled a sphere on the page corner—a wiry sun—and shaded it to 3Dness as best I could. A dormant frustration was being released. Practice makes perfect. But all I felt was frustration.

***

She wore a grand Victorian dress, three times her width at the hip but slender up top. It was a brilliant vermillion. It contrasted sharply with the burgundy couch. Her red dress and gold hair glowed from sunlight creeping through the windowpanes. By her lap were her folded hands. When she swiveled in my direction or cautioned Edna not to run off, the tassels of her dress swung like Christmas lights. The arc of her dimples curved like the sun. My hands felt weak. Despite their numbness, I continued sketching.

“Tis a wonderful morning,” she said confidently. “And, dare I say, you’re quite enthusiastic with your art!” I could feel Susie’s glance land on me as she spoke her faux British accent. Faux not to malign them, but because she marveled at them. She had ever since childhood, for no discernable reason. There wasn’t a time I could remember when she wasn’t imitating their vocal pattern. I eyed her without lifting my head from my page.

“I am. Have to practice.” She nodded.

“Most impressive. It’ll be a masterpiece upon completion. A picturesque utopia.”

I kept drawing. My sketch was of a lake surrounded by a barricade of trees. I shaded the water heavily while the rim remained light scribbles. The trees were towers—tall and imposing. My goal was for the lake to look alive, sanguine. The pines regarded the lake as paltry, but the lake was ready to sally against the pines—despite being severely outnumbered—all in the name of individualism.

My heart fluttered. Susie maintained her gaze on me. On the mandala patterned carpet was Edna, ramming toy cars into each other, making cute explosion noises. The TV was off and the silence only increased my desire to speak with one of my two companions. I steadied my pencil. If I gave in now, it’d just be easier to put off drawing later. Practice was the only way to mastery.

I glanced at Susie periodically. She maintained her calm, pleasant demeanor. Between glances I’d continue drawing. When I looked in her direction again, she was leaning towards me, pert, grinning.

“The Autumn Festival shall commence in a mere three days! Tell me, Thomas, are you looking forward to it?”

The Festival never failed to enliven Haroville. Orange flames from bamboo torches irradiated the town; elders gossiped and ate while savoring brisk weather; children paraded the town square with miniature drums. Since Susie was home, I could spend the Festival with her. I wanted to tell her this, but I had a responsibility.

“I think,” I looked up at her. “I think the whole thing will be a fun time…” I resumed drawing.

She let out a sigh and slumped against the couch. Wrapped in the red of her dress, she progressively shrank and dissolved into the burgundy cushions. Was she frowning? To make eye contact would be to sever myself from focus, which I could not afford.

My throbbing fingers began to heal as I put the finishing touches on my drawing. I took a second to glance at the pile I accrued last night and this morning. A smile spread on my lips. So much progress in so little time. Still, something felt off. My chest grew laden with a mass I couldn’t place. Tin foil mashed in tin foil mashed into a voluminous spiked ball.

“Thomas,” Susie said. Her voice was dull, its potency ebbed from fighting some battle of her own. “Do you remember your drawings from childhood?”

I shrugged. “Yeah I remember drawing stuff. But I didn’t know anything back then. Kids’ll scrawl stick figures and know nothing about still lifes.” That was something I was grateful for at least. Despite the severity of my art slump, it couldn’t be denied that before it started, I spent years studying and practicing.

“It doesn’t matter what skills you used to know, Thomas. You were always so happy doing it. Drawing. Why aren’t you happy now?”

My fingers started tingling. “Because I have to draw. I want to draw. But every time I put my pencil to the page, my brain shuts down. It sputters and twists, and fumes plume like plane exhaust. It’s gotten so bad I can’t even start anymore.” I held up my page to her face with both hands and shook it. “Apparently the only way to get anything done is if I force it. So I can’t play with you and Edna. I need to do this.”

Edna dropped her toys. She turned to me, eyes wide, face crumpled. Susie made a loud sigh and trudged out the room.

“Hey. Susie, wait!”

But she didn’t answer. It was just me and my art—and Edna. I couldn’t let her burst into tears. I ran to her with one of my finished drawings.

“Hey, hey, don’t cry. Everything’s fine.” I folded it into a paper airplane. “See? No reason to cry.” She looked at the shape in wonder. Why was I showing her this? She could poke her eye out. I held the plane just above her reach. But she didn’t even try to grab it. The triangular wings mesmerized her.

Hurried stomps came from the stairway. Susie returned with a cardboard box.

“Alright. Take a look at this,” she said before dropping the behemoth on the floor.

“What’s this?” I walked over to her.

“Your old stuff. Did you think I had forgot about it?”

“Forgot about wha—” and there it was. A pile of caped stick figures, crayon houses with sharpie roofs, oval torsoed and oval headed and rectangle footed dogs, and green upward highlighter swipes to indicate grass; it was everything I made in kindergarten.

She said, “You gave me every drawing of yours. Art made you so happy.”

“Yeah. It’s just. It’s so hard to focus. Link is out in college and I’m still here. Maybe I stopped because everything just felt so… hopeless.”

“I can take you out of here.”

***

Link and I were hunched over a table in the town square, he chomping on a massive turkey leg, I etching details onto the finer parts of my drawing. Torches brought illumination to us and a dusk Haroville. The town wasn’t unlively. Huddles of townsfolk chattered amongst each other or danced in place. Tambourine taps, xylophone pings, and tings from a triangle rang from every corner. The Autumn Festival was in full swing. In its honor, I was drawing a still life of the statues gathered around us. Zeus and his cohorts were in it of course, but I decided to give the spotlight to the lesser Greeks. Circe and Icarus.

Having maimed his turkey leg, Link looked up from his plate and asked me what’s next.

“I dunno. Now that my drawing mojo is back, I’ve got a lot more free time. I don’t have any immediate plans, but I do have some ideas for the future.”

“No, I meant, what’s next to eat.”

“Oh… Go get a plate and figure out yourself.”

“Don’t have to tell me twice. But uh… did you ever solve that Susie dilemma?”

Like always, I knew the question would come up. Instead of blushing or squirming, I turned from him and eyed a table behind the fountain. Susie and Terry were chatting it up. Their voices were drowned out by the music, but, for a moment, they looked at me. A mirthful Susie waved, and Terry mouthed well done.

I waved back. Then I looked to Link.

“Susie and I are going to travel the country,” I said. It didn’t matter what Uncle Chuck or Mr. Clarke thought. Independence was our right. “And after that? Somehow, someway, I’ll make art fit for a gallery.”

- Autumn Festival - December 11, 2021

- Patience Is A Game He’s Not Made For - February 13, 2021

- Your Training Never Ends - July 15, 2020