An Ice Cream

written by: Rodney Ison

After concluding his business with John Russell, Jeremy walked with Rupert to where he, Lucy and Agnes had agreed to meet, at the home of little Daisy Morgan. Although Agnes was six years Daisy’s senior, she found the imaginative mind of the five year old was entrancing, and Daisy and Roderick, who was her contemporary, had hit it off the first time they met.

“Can we leave the children with you while we finish up here in the village? Mrs. Morgan.”

“Why of course you can, it’ll be a pleasure to have them,” came the immediate reply. Children were Elly Morgan’s life, with five of her own two more made little, difference.

Soon after they’d met up at the house they heard the singular cry of the ice cream vendor in the street, ‘guy-ze-guy-ze,’ it rang out, a familiar call guaranteed to bring the children running. This was nineteen thirty five, and before those hideous chimes we hear today from street vendors of ice cream. The manner of advertising his presence with such a distinctive cry was not planned in any way; as with so many things in those days, it just happened, as had his vocation, ice cream maker and vendor. He was, originally, from Italy; how or why he came to be here in the centre of England, in Leicestershire, no-one knew, but here he was, and because nobody makes ice cream like the Italians, it was entirely natural that he should support himself by doing what he was good at, making ice cream.

His name was Miranallti, but the children called him ‘Onion Head.’ This may have been because he was mostly bald and his pate, always a rich, brown tanned by the sun, resembled an onion: Or it could have been because ‘Onion Head’ is easier to say then Miranallti: Children have a way of coping with these things.

In those days our ice cream vendor carried his wares in an insulated container on an adapted bicycle. The front wheel had been exchanged for a large, insulated box in which the delicious concoction was kept and to which two small wheels had been attached effectively making the bicycle into a tricycle. The handlebars had been taken off, so steering was accomplished by a solid bar running the length of the box. Needless, to say, progress on such a vehicle was painfully slow.

“Ooh! May we have an ice cream, mama,” pleaded Agnes.

“Yees!” exclaimed Rupert in entire agreement.

Living in a large house in the country may have seemed desirable but had the drawback that no ice-cream vendor ventured out that far.

“Of course, you can,” their mother replied reaching for her purse, and giving them a thrupp’ny bit* each, then another thruppence, adding, “and get one for Daisy too. That’s to say thank-you for looking after them,” aside to her mother.

“I’m sure I’d do it for nothing, Miss Lucy,” she replied, “but thank you, it’s very good of you.”

“Look after the young ones,” Lucy shouted after Agnes who was making a rapid exit closely followed by Rupert and Daisy.

“Yes, mama,” shouted back in response over her shoulder.

The excited trio made their way to the ice cream cart and found another young lad, Eric, a boy of eleven, Agnes age, was already there with his dog, Mickey. The animal was fond of ice cream and knew if he accompanied his master to the point of sale he was assured of a prize, an ice cream wafer. Well, dogs can’t handle a cornet. He was just being allocated his reward for faithfulness when Agnes and the young ones arrived: “Hello, Eric,” came the laconic greeting from Agnes who genuinely liked the boy but did not want to be seen to express too much interest.

“Hello, Agnes, hello Rupert, hello Daisy,” came the cheerful, polite reply just as Mickey took the position of his prize. The dog began to mouth the wafer from side to side in his mouth because the cold struck his teeth, then trotted off to take up a position in the middle of the gateway to the path to his house to fully consume the delicacy by the mouthing process, after which he continued his repast by washing his face with his paws to get every little vestige of what had stuck to his chops in consequence to the manner of consumption.

It was at this point that another young boy approached the group. He was a little older than Rupert, had been born late in his parents’ lives and was, as it was termed in those days, mentally sub-normal. The blame for such faults was said to be due to the mother’s age but we now know it could, equally, have been because of the father’s age. Suffice to say he was not a normal child. His parents, especially his mother, were ashamed of him and did their best to keep him hidden away. She thought she had been badly done too in life, and that some other, less deserving person than she should have been given a defective child to care for. Surely, she supposed, she merited an off-spring that was accomplished above all others and one she could vaunt as superior due to elite parentage. She believed, furthermore, that she was worth more than to have been reduced to living in a council house, and it should have been her, not Lucy, who should have been living in the big house on the estate, with wealth and servants, and whose lives she would have made insufferable had she been their mistress.

The boy’s name was Jonathan, but the best he could do was to say, ‘Mommer,’ so the local children, enterprising as ever, gave him the nick-name ‘Bomber,’ which infuriated his mother if ever she heard it although it did not seem to bother Jonathan. This suited the persecutors and gave them leave to ridicule her in turn; neither of his parents were well liked.

Agnes was above this: “Have you come to buy an ice cream, Jonathan?” she asked.

The child replied with the other of the two sound he had mastered, “i (as in it) om ole.”

“Do you have any money?” Agnes continued, thinking that perhaps his parents had given him some: Jonathan replied with a blank stare: It was obvious to her he had no concept of money.

Eric, who had been watching the exchange then came up with an idea: “If we ask for a little bit less in our ice cream, cornets we can have the remainder put in one for Jonathan.”

“What a clever idea,” replied Agnes, then needlessly addressed the proposition to Mr. Miranallti who had been listening intently and knew perfectly well what was going on. He proceeded to make up five cornets without comment. The children had not realized the scoop is designed to pick up a measure which could not be conveniently reduced, so they were each being given full measure by the kindness of the vendor, that is, to say a free one for Jonathan.

They stood, contentedly licking their ice creams, pulling funny faces and contorting their necks to lick the back and sides of the cornetto not let any escape by melting, with little Jonathan taking evident pleasure at being in the company of such sociable companions, when their reverie was interrupted by a strident cry: “What do you think you’re doing?” Jonathan’s mother had noticed his absence, or rather his escape from oppression, and come to find him. She strode up to the party in that determined manner which has the obvious intent of causing the most discomfort and unpleasantness possible.

“We didn’t want to leave Jonathan out, Mrs. Berrens. We didn’t think you’d mind,” Agnes tried to reassure her.

“We’re perfectly capable of buying him an ice cream ourselves,” she retorted, assuming that Agnes had paid for the ice-cream herself: “We don’t need your charity,” and so saying, scathingly, she seized the little boy by the upper arm and hawked him off homeward totally unaware of Mr. Miranallti’s kindness.

“Why is Mrs. Berrens being so unkind to Jonathan?” asked Rupert innocently but loud enough for her to hear. The pair had reached the front door of their house by now, with the lad still trying to consume his ice cream by contorting his head and neck and sticking out his tongue as far as it would go to reach the most out of reach concoction. Hearing Rupert’s remark the woman stopped and glared fiercely at him but denied to reply; she knew who Rupert was and thought better of confronting him, small boy though he was. She confined her response to snatching the ice cream from Johnathan’s hand and depositing it unceremoniously onto the garden, then went in and slammed the door loudly behind her.

Mr Miranallti watched the exchange closely without comment.

The four children, completely unphased by the exchange, ran up the street to join Mickey, who was still washing his face, and finish the enjoyment of their ice creams together amidst pleasant banter: ‘You’ve got some on your nose.’ ‘Look, it’s running down your arm.’ ‘Be quick, Daisy, it’ll melt.’ ‘I’m nibbling all the way around mine before it melts.’ All the while with Mickey looked on plaintively hoping someone would take pity on him. He got the tips of the cornets for which he was entirely grateful although they contained no ice-cream.

What to do next? It was agreed they would all repair to Daisy’s house to play snap. Mrs. Morgan, always delighted in the company of children, was happy to entertain them, so sat them around the kitchen table, provided lemonade and dandelion and burdock to drink and gave them a well, worn pack of cards. The kitchen soon became alive with the shouts of the card players, but Eric saw that Rupert, who was not used to the game, was missing every time because he was not quick enough to call out ‘snap,’ and was fast running out of cards. He, therefore, contrived to help him: He carefully watched until he put down a consecutive card, then quickly put his hand over his and called out: ‘Snap. Oh dear, Rupert’s hand was still over the cards, so they belong to him, well done Rupert,’ as he collected them together to give to the jubilant little fellow, pleased that at last, he was winning something.

‘What a marvellous fellow,’ Agnes said to herself: ‘He’s so kind and thoughtful.’

Jeremy and Lucy walked back to Mrs Morgan’s after concluding their business with Mabel Dearing concerning John Russell, walked back hand in hand for all the village to see that the people from the big house were human too, and clearly very much in love with one another as they laughed and smiled at the recent events. They walked straight into the kitchen at Mrs. Morgan’s; that’s what you did in those days when you knew you were always welcome.

“Look how happy they are,” Lucy commented as soon as she entered: “We could hear you way down the street. Thank you so much, Elly, for looking after them. You’ve been a great, help.”

“It’s always a pleasure, Miss Lucy, the children are welcome any time.”

“Can Daisy come to tea tomorrow mama?” Rupert then asked peremptorily, unaware that he was putting his mother on the spot.

“You shouldn’t ask, Rupert,” exclaimed Agnes correcting him.

“That’s all-right, Agnes,” Lucy replied without hesitation: “Of course she can if she wants to. Would you like to come to tea, Daisy?”

“Ooh! Yes please,” replied Daisy, clapping her hands together and making little jumps up and down in her delight.

“That’s settled, then,” Lucy concluded with a whimsical smile on her face at the way the children had got what they both wanted.

“And can Eric come too?” Agnes spoke up, concerned that he should not be left out.

“Yes. I was going to ask. Do you want to come to tea too, Eric?” fully aware the answer would be ‘yes.’

“Oh, I’d love to, Miss Lucy. Thank you for asking me.”

“I’ll come in tomorrow and pick you both up here, shall I? Say two o’clock.”

“I’ll be here, Miss Lucy,” replied Eric promptly in his excitement at going to the big house for tea and being with Agnes.

“I’ll make sure they’re ready for you when you get here, Lucy,” Mrs. Morgan assured her.

“Let’s go, then, children,” Jeremy broke in: “That’s all arranged.”

During the drive back to Water-leas Lucy went over the day’s events in her head, turning frequently to look at her husband as he drove, a look both of pride and affection; she was reinforcing the strong bond between them, made stronger by the proposal to care for old John Russell in his old age, and the evident pleasure expressed by the children at being invited to tea.

Back at the estate house, Water-leas, Lucy went straight to the kitchen to see Betty, the housekeeper and cook, to tell her of the tea party the next day and arrange a menu with her and little Jenny, the maid of all sorts who came from the village six days a week, because she too would be involved and knew very well, perhaps better than the adults, what the children liked.

“Daisy and Rupert can eat in here where we can keep an eye on them, but I think Agnes and Eric can eat in the snug. It’ll be a little more grown up for them,” Lucy suggested.

“It’s going to be a nice, day tomorrow Miss Lucy,” Jenny piped up in her trilling, little voice, “and I could set two tables up on the grass under the beech tree and keep an eye on ‘em from ‘ere. They’d be all right.”

“Yees, ooh yees,” echoed Agnes and Rupert in unison, very keen on the idea.

“Eric and me, would make sure Daisy and Rupert behaved themselves mama,” Agnes volunteered.

“All-right, if that’s what you want. So be it,” said with a smile to Betty who returned her dead-pan look confirming she was, in agreement.

The next day Lucy fetched the two children from the village, put them in the back of the car where they sat demure and quiet all agog to be taken to the house in this splendid motor car, and dropped them at the front door to be collected there by Agnes and Roderick who took them immediately to the kitchen to see what was being prepared for them. Eric was quite overawed at being invited to the home of this grand, family but Daisy took it all in her stride. She was a precocious little child.

“Go and show Daisy and Eric round the garden children. You mustn’t interrupt Betty and Jenny while they’re working,” Lucy told them, then, when they had disappeared in a whirlwind of excitement, set too helping herself. “What do you want me to do, Betty,” she asked.

“Can you see to the sandwiches, Lucy, thank you. I’ve got a special treat for the little ones which needs churning, ice cream, but don’t tell them, it’s a surprise.”

“Oh, they’ll love that. So, will I if you make enough.”

“I’ve made plenty Lucy, don’t you worry. There’s enough for everybody.”

The four children retired to the kitchen garden, Agnes pairing up with Eric, while Rupert undertook to shepherd Daisy around, fearful she could get lost. The two young ones soon came across the tiny body of a dead vole and stopped to seriously contemplate the nature of death, when George, the gardener, came upon them: “Now, my dears, what ‘ave we here?”

“It looks like it fell out of the sky,” piped up Daisy in a comment of the manner of demise.

“No, no,” responded George knowingly: “It looks like somebody stood on it with their big boots. Shall we bury it, after all, it was one of God’s little creatures?” Then he proceeded to dig a shallow hole in the corner of a vegetable patch, scoop up the body on his spade, deposit it carefully and respectfully in the hole and cover it over with soil: “There, I think we’ve done the right thing, don’t you?” he concluded the procedure.

For the next half hour or so the garden and neighbouring wildflower meadow resounded to the happy cries of children playing agreeably. After a happy time, they set out on their way back to the house for the tea being prepared for them, across the wildflower meadow where Daisy took it into her head to pick some flowers for Lucy to say, ‘thank-you.’ It had not occurred to the little girl that they belonged to Lucy anyway; that did not matter; they were a present and it’s the thought that counts.

The party burst into the kitchen agog to tell their adventure, Daisy carelessly depositing the flowers on the kitchen table saying: “I brought these for you to say thank-you, Miss Lucy.” Jenny, sharp as ever, quickly found a vase which she filled with water, and dexterously, with the aplomb that some women seem to have, pushed the bouquet into it rearranging a few flowers only but managing to make it look as if a professional flower arranger had done it.

After receiving appreciation from her host, Daisy immediately lost interest and began to relate the find in the vegetable garden to a patient Lucy, concluding: “An,’ an’ George said somebody must’ve stood on it wiv’ their big boops an,’ an,’ it was one of God’s little capers,” which brought a wry smile to the faces of the mature women present. That event out of the way having been received with all, due seriousness, she turned to look at the food the likes of which she had never seen before.

Everyone was called upon to carry the plates of food to the tables outside which had been set up by George and his young assistant, Toby. The children took their places, Agnes and Eric at one table, Daisy and Rupert at the other. Unused to saying grace, which was customary in this house, Daisy in her eagerness took a sandwich and began eating.

“Shall we say grace, children,” Lucy announced, quietly and calmly.

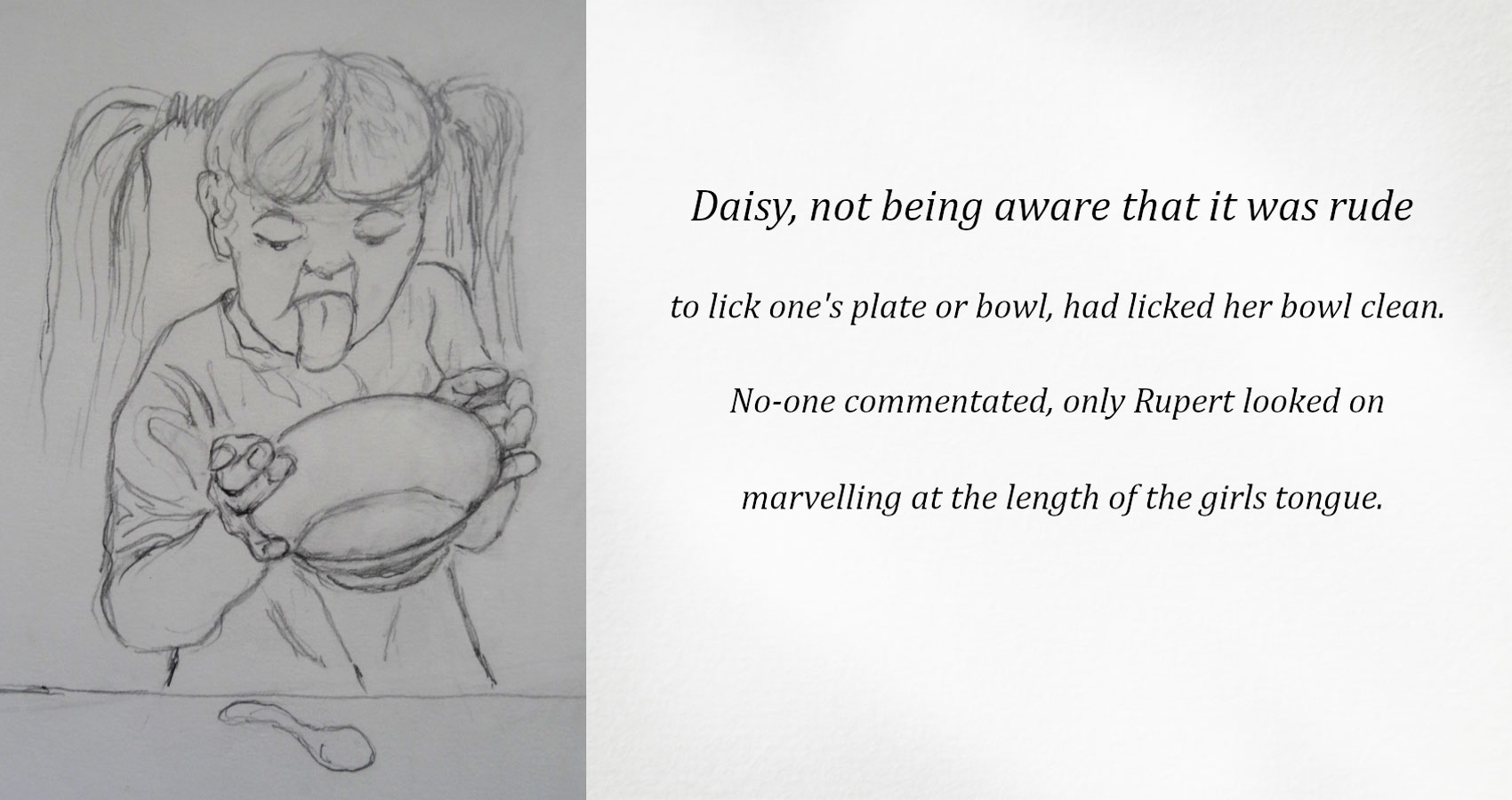

Daisy put down her sandwich sheepishly and copied Rupert who had put his hands together and closed his eyes. Grace over they all set to eating which brought a sudden silence over the little group. After a while, however, the lively chatter started again and continued until Betty and Jenny brought out the ‘piece de resistance,’ ice cream, huge bowls of it. The chorus of joy and exclamations of pleasure were something to be seen, and once more silence descended on the group until every scrap was gone, and Daisy, not being aware that it was rude to lick one’s plate or bowl, had licked her bowl clean. No-one commented, only Rupert looked on marvelling at the length of the little girl’s tongue.

With a bowl of ice-cream each, Lucy and Jeremy were standing at the back door watching the scene with the immense pleasure that they had been able to make the children so happy. While sharing their happiness and looking on, Jeremy thought to himself: ‘In all this estate what really matters is concentrated here in front of us, the children enjoying themselves.’

Lucy, spurred on herself by the same pleasure, broached an idea to her husband: “Why don’t we put on an annual children’s fete for all the children around here, like the village fete but for the children. We could get in caterers to manage the food, and there is any number of willing helpers who’ll help, especially organising the children’s games. And we could ask Gino Miranallti to bring a container of ice-cream as a special treat. What do you think?”

“I think it’s a fabulous idea.”

“Shall we ask your father’s permission, after all, he’s still head of the estate.”

“No. He’ll just say ‘no’ and put an end to it. I’m the estate manager and I don’t need his permission. Just do it then he can’t say no. Can I leave it to you to organise?”

“Okay,” Lucy responded with a wry smile: “I’ll get on with it as you say. And something else while we’re on the subject, of doing things for children and you’re in such a generous mood, Eric has done very well at school and won a scholarship to grammar school, but his parents say they can’t afford to send him. Do you think we could do something to help him? I’d hate to see his talent go to waste, he’s such a deserving lad.”

“Why not. We could create a bursary as an award for deserving pupils which wouldn’t be seen, as a charity handout. Keep it going as a year on year thing. I’ll pay for it out of my own pocket, or, rather, we’ll pay for it out of our collective pocket, but we’ll call it the Lucy Morton Award because you thought of it.”

A surge of happiness and affection for her husband took hold of Lucy. She felt that familiar tingling that could be allayed by one thing only: “I should like to go to bed early if that’s all right with you, darling,” she murmured to him.

He put his free hand around her waist and pressed himself against her, felt that surge of delight that comes with the expectation and murmured: “Isn’t it always all-right,” kissing the hair on the top of her head: “If this is what ice cream does to you I think you should have some every day.”

* Thrupp’ny bit. Twelve-sided bronze coin in pre-decimal currency. There were twenty shillings to the pound and twelve pence to the shilling making two hundred and forty pence (penny singular) to the pound. The shilling (a bob) was sub-divided into a sixpence (a tanner), sub-divided again into three pence (the thrupp’ny bit), after that the halfpenny (ha’pny), from which comes the expression ‘you daft ha’porth,’ that is, not a full penny, and the quarter of a penny (a farthing).

‘Ah, those were the days.’

- An Ice Cream - December 29, 2018

- The Visit To The Café - July 31, 2018